Barrackpore mutiny of 1824 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Barrackpore mutiny of 1824 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Anglo-Burmese War | |||||||

A Subadar of the early nineteenth century from the Bengal Native Infantry in his army uniform (published in An Assemblage of Indian Army Soldiers & Uniforms from the original paintings by the late Chater Paul Chater) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Indian rebel sepoys of the Bengal Native Infantry | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

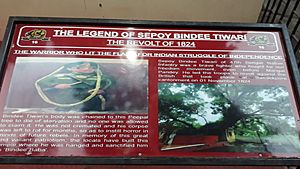

Bindee (Binda) Tiwary |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Indian sepoys of

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 killed from friendly fire | 12 hanged 180 sepoys killed during the conflict. |

||||||

The Barrackpore mutiny was a rebellion by Indian soldiers, called sepoys, against their British officers. It happened in November 1824 in Barrackpore, India. At this time, the British East India Company ruled parts of India. They were fighting a war called the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826). The leader in India was the Governor-General of Bengal, William Amherst, 1st Earl Amherst.

The mutiny started because the British did not understand Indian customs. Also, the soldiers were not given enough supplies. This made the sepoys of the Bengal Native Infantry very angry. They had just finished a long march. They needed help to carry their things, but no transport was given. Many sepoys also did not want to travel by sea. This was because of a cultural belief called kala pani. It meant crossing the sea could make them lose their social status.

When the soldiers refused to march, British leaders tried to solve the problem. But the talks failed. The British Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Edward Paget, ordered the sepoys to drop their weapons. When they refused, their camp was attacked. Many sepoys were killed. After the mutiny, some leaders were hanged. Others were sent to prison. The 47th Regiment, which was involved, was shut down.

Contents

Why the Mutiny Happened

The Long March and Fears

In October 1824, three regiments of Indian soldiers were told to march. They had to go about 800 kilometers (500 miles) from Barrackpore to Chittagong. This was to prepare for fighting in Burma. The soldiers had just marched about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) to Barrackpore. They were tired and did not want another long journey.

There were also rumors that the Burmese had magical powers. This made the Indian soldiers scared. Their morale was low, especially after the Burmese won a battle at Ramu. Most of these soldiers were Hindu. They worried about crossing the sea. This was due to the kala pani taboo.

Lack of Supplies

The soldiers were tired and scared, but they also had no way to carry their gear. Each soldier had heavy brass cooking pots and bedding. They could not carry these items plus their weapons. Usually, bullocks pulled carts for their belongings. But for this march, there were no bullocks. Most animals had been taken for another sea trip to Rangoon.

The few bullocks left were very expensive. The soldiers asked the government to provide bullocks. Or, they asked for double batta. Batta was extra money paid when soldiers were in dangerous areas. This money would help them buy bullocks. But their requests were ignored. They were told to carry what they could and leave the rest.

Officers offered some money, but it was not enough. The soldiers would still have to pay for baggage themselves. A Muslim Indian officer, a Subedar major, made things worse. He threatened to send them by sea if they kept complaining.

What Happened During the Rebellion

The 47th Regiment was told to march first on November 1, 1824. On that day, the soldiers of the 47th Native Infantry came to the parade ground without their bags. They refused to bring them. They again demanded bullocks or double batta. They would not march without their problems being fixed.

Their commanding officer, General Dalzell, could not calm them down. He went to Calcutta to talk to General Sir Edward Paget. Other regiments also became upset. About 20 soldiers from the 26th BNI and 160 from the 62nd BNI joined the upset soldiers of the 47th Regiment.

The soldiers, led by Bindee Tiwari, stayed on the parade ground. They sent a message to General Paget. They explained their actions were due to religious beliefs. They asked to leave the army if their demands were not met. Paget said he would only listen if they put down their weapons first. The soldiers did not agree to this.

Paget saw this as an armed rebellion. He called for more soldiers. Two British regiments came from Calcutta: the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot and the 1st (Royal) Regiment. He also brought horse artillery from nearby Dum Dum.

On the morning of November 2, the loyal soldiers surrounded the upset sepoys. A final message was sent to the rebels. They were told to put down their weapons. They were given only ten minutes to decide. The sepoys either hesitated or refused. Paget then ordered two cannons to fire on them. Other British soldiers attacked from all sides.

Many sepoys tried to run away. Some jumped into the Hooghly River and drowned. Others ran into houses for safety. But the loyal soldiers followed them and killed them. Many innocent people, including women and children, were also killed. Later, it was found that the Indian soldiers' guns were not loaded. This suggests they did not plan to use violence.

Deaths and Injuries

About 180 of the 1,400 rebel soldiers were killed during the attack. However, the exact number of deaths is not clear. A local newspaper reported about 100 deaths. Later, a British politician named Joseph Hume said 400 to 600 people died. But the government said no more than 180 died.

What Happened Next

Punishing the Rebels

Most of the remaining rebel soldiers were caught. On November 2, eleven leaders were quickly tried. They were sentenced to death by hanging. Six were from the 47th BNI, four from the 62nd BNI, and one from the 26th BNI. They were hanged on the same day. About 52 soldiers were sentenced to 14 years of hard labor. Others got shorter sentences.

On November 4, the 47th Regiment was officially disbanded. Its Indian officers were removed from duty. They were seen as untrustworthy because the mutiny happened under their watch. The British officers were moved to a new regiment. On November 9, Bindee Tiwari was arrested. He was given a very harsh punishment. He was hanged and his body was left on display for months.

News Was Hidden

The British government tried to keep the news of the Barrackpore events quiet. They did not want people to know about the violence used. A short official note was published in the Calcutta Gazette. It made the incident seem minor and did not mention any deaths. Another local newspaper also published a short report. It did not give many details. Most people in India and Britain did not know the full story.

Later Criticism

About six months later, a London newspaper called The Oriental Herald published a story. It called the event the "Barrackpore Massacre." The newspaper strongly criticized the British officers, especially General Paget. It said he used too much violence against a peaceful protest. It also demanded better pay for the sepoys and transport for their luggage. The report also blamed Governor General Amherst for the problem getting worse.

Long-Term Effects

After the mutiny was stopped, many sepoys left the British army. An investigation was set up. It found that the sepoys had good reasons for their complaints. Indian units that served in general areas were given the things the rebels had asked for. The 1824 event caused a lot of distrust between British officers and Indian soldiers. This damaged their relationship for a long time.

No officers, including Paget, were punished for their actions. Amherst almost lost his job for how he handled the situation. But he was allowed to keep his position.

Debate in British Parliament

On March 22, 1827, the British Parliament discussed the Barrackpore Mutiny. Joseph Hume, a politician from the opposition, spoke about the event. He criticized the army's actions. He asked for a new investigation to find out who was truly responsible. He also said that the report from the first investigation was being hidden. He wanted the full report to be shown to Parliament.

Other politicians supported Amherst and Paget. In the end, the idea for a new investigation was voted down.

Why This Event Was Important

Barrackpore was also the site of another mutiny 33 years later. This happened on March 29, 1857, involving a sepoy named Mangal Pandey. This later event helped start the big Indian rebellion of 1857.

The events of 1824 were remembered by both Britons and Indians for many years. Some felt it gave Indian soldiers a reason to kill British officers in 1857.

Memorial

Bindee Tiwari became a hero to Indian soldiers and locals after his death. Six months after he died, Indian sepoys and local people built a temple near where he was executed. This temple is still there today and is known as Binda Baba temple.

See also

Sources

- The Asiatic Journal And Monthly Miscellany. 23. London: Parbury, Allen, & Co. 1827. OCLC 1514448. https://books.google.com/books?id=QBMoAAAAYAAJ&q=Barrackpore+Mutiny+of+1824&pg=PA168.

- The Edinburgh Annual Register for 1824. 17. Edinburgh: James Ballantyne and Co. 1825. OCLC 4043682. https://books.google.com/books?id=TXdZAAAAIAAJ&q=Barrackpore&pg=PA215.

- The Oriental Herald and Journal of General Literature. 5. London: Sandford Arnot. 1825. OCLC 231706887. https://books.google.com/books?id=lQIbAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA13.

- The Oriental Herald And Journal of General Literature. 13. London: Sandford Arnot. 1827. OCLC 457180515. https://books.google.com/books?id=AxoYAAAAYAAJ&q=Hume%20Barrackpore%20Mutiny&pg=PA177.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |