Battle of Brightlingsea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Brightlingsea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Protesters blocking the road to Brightlingsea wharf in 1995.

|

||||

| Date | 16 January - 30 October 1995 | |||

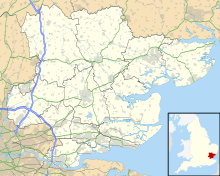

| Location |

51°49′N 1°02′E / 51.81°N 1.03°E |

|||

| Caused by | Opposition to the live export of cattle from the UK to mainland Europe | |||

| Goals | Halting of live export through Brightlingsea port | |||

| Methods | Picketing, Sit-in, Civil resistance | |||

| Status | Ended | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

|

||||

| Lead figures | ||||

|

||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Arrested | 598 | |||

The Battle of Brightlingsea was a series of protests in Brightlingsea, England. These protests happened between 16 January and 30 October 1995. People gathered to stop animals like cattle and sheep from being sent alive from the town's port to other countries. The media first used the name "Battle of Brightlingsea" after the police used special crowd control methods against the protesters.

By 1995, many people in the UK were worried about how farm animals were raised, moved, and killed. Animals like cattle, young calves, and sheep were being sent to mainland Europe. Before this, large ferry companies had stopped carrying live animals. This was because people were very concerned about the suffering of animals packed into trucks for long trips. Two big animal welfare groups, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) and Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), wanted to stop all live exports. They suggested that animal journeys should be no longer than eight hours. At that time, European rules allowed journeys up to 24 hours without food or water. Because the big ferries stopped, exporters started using smaller ports like Brightlingsea.

The protests were mostly made up of people who lived in Brightlingsea. They ended on 30 October 1995. The exporters announced they would no longer send animals through the town. This was because the daily protests caused too much trouble and cost them extra money. Live animal exports continued from other small ports until February 1996. At that time, the European Union stopped all meat exports from Britain. This was due to worries about "mad cow disease" entering the food chain. This ban was lifted in 2006.

Contents

Why People Protested

Long Journeys for Animals

In the early 1990s, many places where animals were slaughtered (called abattoirs) in Britain closed down. This meant animals had to travel much longer distances by road. For some farmers, it became cheaper to send their animals to Europe to be slaughtered. Under European rules, animals could travel for up to 24 hours without food or water. However, investigations showed that even these long travel times were often ignored.

Animal welfare groups in Britain, like CIWF and the RSPCA, spoke out against live exports. They were worried about the suffering of cattle during these very long journeys. The RSPCA believed that "All animals should be slaughtered as close as possible to where they are reared." The British Veterinary Association agreed, saying animals should be killed near where they were raised.

People were also concerned about the export of hundreds of thousands of young calves each year to Europe. There, they were kept in dark, small pens called "veal crates." They were fed a special diet to make their meat pale. Veal crates had been banned in Britain since 1990. However, there were no rules to stop calves from being sent to other countries that still used these crates.

After 1993, live animals were seen as "agricultural products" in Europe. This meant that trying to limit their travel times was seen as stopping trade, which was against the law.

Making More Money

Sending live animals to France cost more than sending meat. But British lambs killed in French abattoirs got a French meat stamp. This meant the meat could be sold as "French produced" for a higher price. This extra money made up for the higher transport costs.

A similar thing happened in Spain. Animals were sent there to be "fattened." This got around a British ban on sending animals to Spanish abattoirs. The ban was because people were upset about the standards there. After a few days in Spain, the animals were called "Spanish-reared" and then slaughtered.

Live animals also brought extra profit to slaughterhouses. They could sell parts like organs, hides (skins), and wool (from sheep), which were called the "fifth quarter."

Government Response

In April 1994, Nicholas Soames, a government minister, said that a complete ban on live exports was not possible. He explained it would break European Union law. He said the government knew how strongly people felt. However, their legal experts said they could not stop trade just to have higher animal welfare standards. This news disappointed many people who cared about animal suffering.

Ferry Services Stop

Public Pressure Works

In August 1994, a newspaper reported that British Airways (BA) was flying live sheep. Within a day, BA stopped carrying live animals meant for slaughter. Then, Brittany Ferries announced they would no longer export live animals. Protesters also gathered at ferry terminals in Kent. The offices of Stena Sealink ferries were even attacked.

As a result, Stena Sealink also stopped transporting live animals. A company director said they did it for business reasons. He explained that thousands of customers had written to them, saying they did not want to travel on ferries carrying livestock. P&O also said they would stop carrying animals from October 1994. They said they would only restart if European Union standards improved.

Even ferry companies that did not carry livestock felt they needed to speak out. Sally Ferries UK announced they had not carried live animals for over 13 years.

Exporters Find New Ways

By October 1994, when the ferry bans started, exporters looked for new ways. Smaller companies applied to take over the trade. These new companies planned to carry only animals and cargo. This way, they hoped to avoid public disapproval. One company planned to sail from Harwich, Essex, to France. This was an eight-hour journey, much longer than the usual route.

They also asked to use old East European military transport planes to fly animals to Europe. Campaigners were against this because these planes were not pressurized. Flights using these planes were approved from Humberside Airport to the Netherlands. However, these flights stopped in November 1994 because of strong public feeling. Other flights took place from airports in Belfast, Glasgow, Bournemouth, and Coventry.

In October 1994, a ferry carrying 3,000 lambs sailed from Grimsby to Calais. This journey took about 18 hours. The animals then traveled for 10 hours by road to a slaughterhouse in France. The RSPCA said this was "appalling" and "simply not necessary." In November 1994, another company announced they would transport livestock from Sheerness in Kent to the Netherlands. After the first shipment, they delayed more sailings due to threats.

By January 1995, Dover had also banned livestock. The only places still available for live exports were Coventry Airport, Plymouth, and Shoreham-by-Sea. Shoreham became a place of daily protests. Protesters tried to stop animal trucks from entering the harbor.

Exports Through Brightlingsea

On 11 January 1995, it was announced that exporters planned to use Brightlingsea. Everyone knew that an attempt to load animals at the town's wharf was coming soon. Newspapers warned that Brightlingsea might become the next Shoreham-by-Sea.

Brightlingsea was perfect for protesters and the media. The road to the wharf was very narrow and easy to block. This also meant people on the roadside could get close to the trucks and touch the animals. The police described the wharf as being at "the wrong end of a narrow three mile road in a medieval town."

First Protest

On 16 January, a Danish ship called the Caroline was set to sail from Brightlingsea. It was carrying 2,000 sheep going to Belgium. Local residents quickly formed a protest group called Brightlingsea Against Live Exports (BALE). About 1,500 people, mostly locals, gathered. When the first truck arrived, carrying 400 sheep, the protest was mostly peaceful. People sat and lay in the road to block the truck.

The police decided the truck should turn around because the situation was dangerous. A BALE organizer said they were happy the truck was turned back. However, they were not sure it would be the last one. Exporters complained that the police should have made sure the animals reached the wharf.

Storms Delay Sailings

Plans to try loading the Caroline again were delayed on 17 January. Strong winds meant sailings from Brightlingsea were cancelled. BALE gave out leaflets to every home in the town. They asked people to come to the protest planned for 18 January. They also said they would use boats to stop the Caroline if the roadside protest failed.

Police Actions and Protester Reactions

An exporter named Roger Mills threatened to sue the police. He said they failed to escort his sheep on 16 January. He also warned he would transport animals on 18 January "with or without police support." In response, the police planned a very large operation, called Operation Gunfleet.

On 18 January, trucks carrying 2,000 sheep drove through the town. About 500 protesters tried to block them. The police sent about 300 officers, many in riot gear. Police dragged away the first protesters who sat in the road. They also pushed or hit anyone trying to take their place. By 10:00 AM, the animals were loaded onto the Caroline. The ship left the harbor successfully, despite protesters in inflatable boats. The exporter said the police did a "super operation."

Essex Police received over 200 complaints. People said the police used "excessive riot-style violence." One protester said they were sitting peacefully when police in riot gear "just steamed in." She said they were treated "like the worst kind of football hooligans." The mayor of Brightlingsea, Rick Morgan, said:

I saw nothing but a peaceful protest. The reaction by the police was just over the top. The town is united against this live animal trade and these were local people attempting to make a peaceful protest. They included pensioners, children and mothers with babies.

Another protester described the police actions as "frightening and sinister." He said the police seemed "excessively aggressive." Later in the campaign, the situation became more violent. Fights broke out between protesters and police. Objects like bottles and stones were used.

Who Were the Protesters?

One interesting thing about the Brightlingsea protests was who the protesters were. Most were local people. Many had never protested about anything before. Surveys showed that:

- 82% of the protesters were women.

- 81% had never protested before.

- 73% were between 41 and 70 years old.

- 71% lived in Brightlingsea.

- 38% were retired.

Both the media and the police were surprised by how much support the protest received. The presence of so many older people and mothers with young children challenged the usual idea of an animal rights protester. The media expected to see typical activists. Instead, they found many middle-class adults protesting. One newspaper described the protesters as "middle class, moral and mad as hell."

Legal Challenges

Some legal cases came from the protests.

Court Orders

On 29 August 1995, an exporter named Roger Mills asked the High Court to ban 12 named protesters from blocking his trucks. This was thought to be the first time such an order was asked for against regular members of the public. The judge did not grant the immediate ban.

On 22 September 1995, the case was heard again. Mills also asked for £500,000 in costs and damages from the protesters. He claimed the large number of arrests (583 at that point) and the actions of BALE were a "conspiracy." He said the protesters were breaking the law and encouraging others to do the same. The judge replied that sometimes "unlawful activities gained the admiration of law-abiding citizens." He mentioned that what Mahatma Gandhi did was against the law, but most people approved of it. The court order was not granted.

Tilly Merritt's Case

In January 1996, Tilly Merritt, a 79-year-old woman from Brightlingsea, was found guilty of a minor offense. She had sprayed a police officer with water from a garden hose during a protest in February 1995. She was sentenced to two days in prison when she refused to pay a fine of £302. However, people who supported her paid the fine while she was waiting to go to prison, and she was released.

Roger Mills' Case

On 1 March 1996, Roger Mills was found guilty of dangerous driving. This happened during the 1995 protests when he deliberately drove his vehicle into a group of protesters. He was fined £1000 and banned from driving for 12 months.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |