Benevolence (tax) facts for kids

A benevolence, sometimes called a loving contribution or free gift, was a special type of tax used by several English kings from the 1400s to the 1600s. Even though it was presented as a helpful gift to the king, people were often forced to pay. The king would send officials or letters to towns. These explained the king's money problems and asked the richest people to give money. People found it very hard to refuse. They could only say no if they claimed the king didn't really need the money or that they were too poor. This was almost impossible to do. Benevolences allowed the king to raise money without asking Parliament, which usually had to approve any new taxes.

Edward IV first used a benevolence in 1473. It brought in a lot of money for him. He made similar demands before the invasion of Scotland in 1482, which also filled the royal treasury. However, these "gifts" were very unpopular. They gave Edward a reputation for being greedy. Richard III tried to ask for similar payments. But Parliament strongly criticized these taxes, calling them unfair and new. Richard's benevolences were not collected, and Parliament made them illegal in 1484.

Henry VII, who took the throne from Richard, ignored this law. He asked for a benevolence in 1491. Parliament supported his actions, though not everyone in the country did. He collected £48,000. Henry VIII also collected benevolences in 1525 and 1545. The first one led to a rebellion and was stopped. The second one brought in £120,000. During Elizabeth I's long rule, benevolences were only asked for a few times in the 1580s and 1590s. They were only asked from small groups of people and raised small amounts. Benevolences became more and more unpopular. Writers at the time criticized them, which made Elizabeth's government angry. The last benevolence of the Tudor period was collected in 1599.

Benevolences were used again when James I became king. His Parliament was difficult, so he used benevolences to get money without their approval in 1614. This worked well. But another benevolence in 1620, meant to help Frederick V of the Palatinate, did not work. This forced James to call Parliament the next year. No more benevolences were collected after that. However, both James and his son Charles I thought about using them again during their reigns.

Contents

How Kings Collected Benevolences

Kings collected benevolences in ways similar to how they collected forced loans. Officials, often wealthy gentlemen, would travel from town to town. They would explain why the king needed the money, usually saying it was for the safety of the country. Then, they would ask the town's gentlemen for a "gift." Sometimes, the king would send letters directly to the richest people in town, explaining the danger.

Benevolences were often presented as a way to help the king instead of serving in the military during a crisis. Legally, these payments were supposed to be voluntary. But in reality, people usually could not refuse. They could only argue about how much they would give. The only way to avoid paying was to say the king didn't really need the money or that you were too poor. This was very difficult, almost impossible, to do.

Early Benevolences: 1473–1484

Historians say the idea of giving "benevolence" to help the king started in the early 1300s. At that time, requests for taxes or loans began to emphasize both "obligation" (duty) and "benevolence" (goodwill).

The first English king to truly use a benevolence was Edward IV in 1473. He had previously used forced loans. But the word "benevolence" meant he didn't have to promise to pay his subjects back. Also, forced loans were expected to be reasonable. But goodwill towards a king was supposed to be endless. For Edward, benevolences were a new way to get money without Parliament's approval. This added to the already high taxes of the 1470s.

These benevolences were justified by saying that France was a threat to England. The king said he would lead his army himself. In total, the king raised £21,000. This was a huge amount, more than three times what he had raised with an income tax in 1450. The king made similar demands from 1480 to 1482. These were to pay for the English invasion of Scotland in 1482. This benevolence brought in even more money than in 1473, nearly £30,000.

These actions made Edward's rule very unpopular. Dominic Mancini, an Italian visitor to England, wrote that Edward gained a "reputation for avarice" (being very greedy) because he always sought more money this way. This reputation was well-known.

Richard III tried to ask for similar payments several times. But he faced strong opposition from Parliament. Parliament called benevolences "a new imposition" that made subjects pay "against their wills and freedom." They said it caused "great sums of money to their almost utter destruction." A church record, the Croyland Chronicle, also described it as "the laying of the new and unheard-of services of benevolence, where everyone gives what they want to, or more correctly do not want to." In 1484, one of the first laws passed by Richard's only Parliament made benevolences illegal.

Tudor Kings and Benevolences: 1491–1599

After taking the throne from Richard, Henry VII ignored the law against benevolences. He used them often during his rule, calling them "loving contributions." In 1491, seven years after the law was passed, he sent officials to collect these "gifts." Earlier that year, Henry had called a Great Council (a meeting of important people) to approve this benevolence. This made the "contribution" seem more legitimate and supported by the people.

Henry's chief minister, Cardinal Morton, was known for a clever argument used to collect this tax. It was called "Morton's Fork." The argument went like this: if someone lived modestly (simply), they must be saving money, so they could afford a gift for the king. If someone lived luxuriously (richly), they must have extra income, which should be given to the king. This argument became a famous saying for any difficult choice between two bad options. Officials used this argument against anyone who didn't want to pay, demanding huge amounts of money.

Henry also used reasons similar to Edward's 20 years earlier. He emphasized the threat from France. Officials announced that "Charles of France not only unfairly occupies the king's kingdom of France, but threatens the destruction of England." The king said he would personally lead the English army. The benevolence was offered as an alternative to military service.

Parliament later supported this action. A 1496 law even allowed benevolences to be enforced with the threat of death. Historians say that in the early Tudor period, benevolences were used to add to or prepare for regular taxes. They were collected from a small number of wealthy people, not to replace Parliament's grants. One record noted that this tax caused "less grumbling" than previous taxes. This was because only "men of good substance" (wealthy people) were asked to contribute. However, some historians say the benevolence was "paid only with reluctance" by those who had to pay. Henry VII collected £48,000 with this benevolence, more than any king before him.

King Henry VIII continued his father's practice. In 1525, he tried to impose the Amicable Grant. This was a compulsory benevolence (forced gift) taken at a set rate from many people. It was expected to raise a huge £333,000. This was very unpopular because it was different from earlier benevolences. Those had only been for the wealthiest people, and the amount was decided individually. It also didn't help that this "grant" came after two large forced loans in 1522 and 1523, totaling £260,000, which had not yet been repaid.

Many people opposed the Amicable Grant for legal reasons. As historian Michael Bush said, "With no assurance of repayment, and authorized neither by parliament nor church meetings but simply by commission, it smacked of novelty and illegitimacy." The main person promoting the Amicable Grant, Cardinal Wolsey, was criticized as someone who "undermined the Laws and Liberty of England." The officials collecting the Grant found people unwilling to pay. Many claimed poverty to avoid the tax. The forced part of the Grant was soon dropped. After protests started in the South East, followed by riots in Suffolk and Essex, the benevolence was completely given up.

Henry VIII again imposed a benevolence in 1545. This time, Henry was more careful to avoid rebellion. The amounts asked for were lower, and the income level for who had to pay was higher. However, Henry was still strict in enforcing this benevolence. One London official was sent to the Scottish border to fight the Scots as punishment for hesitating to pay his share. The political situation in the 1540s also helped. There was a clear French threat, shown by the 1545 Battle of the Solent. Also, a period of good harvests before 1525 had brought prosperity. This benevolence was successful, raising £120,000 for the Crown.

The first benevolence during Elizabeth I's reign was asked from the clergy (church officials) in the 1580s. To raise £21,000 needed to repair Dover Harbour, which had fallen apart since Henry VIII built it, Elizabeth's Privy Council decided to find a way to get this money. Along with taxes on those who refused to attend church (recusants), ships, and alehouses, the Privy Council sent a benevolence request to the church. They urged wealthy clergymen to donate at least one-tenth of their income for 3 years to fund the repairs. It took 5 years to collect the benevolence. The repairs ended up being mostly funded by ship tariffs (taxes on goods). However, the idea of benevolences from the clergy inspired future financial actions during Elizabeth's reign.

Because of the expensive French wars in the 1590s, Elizabeth's chief advisor, Lord Burghley, planned a benevolence in 1594. It was expected to raise £30,000, but these plans were never carried out. In 1596, another benevolence was asked from the clergy to pay for the Anglo-Spanish War. But the clergy were so unwilling that it was apparently never collected. After Lord Burghley died in 1598, it became clear that the Tudor government was almost bankrupt. A few days after his death, a rumor spread in London that the Queen only had £20,000 in her treasury. Amidst several loans to the government, a benevolence was requested in 1599 from lawyers and officials in various government offices. The government was expected to ask for another soon after. Instead, the Crown sold some of its land, which brought in a healthy sum of £212,000.

Benevolences, along with other ways kings got money without Parliament, became more and more unpopular during Elizabeth's reign. Elizabeth used benevolences much less often than the kings before her. Her government also quickly denied accusations of taking money unfairly. Lord Burghley stated that Elizabeth would never "accept any thing that had been given to her unwillingly," including benevolences "she had no need of." However, this didn't stop writers at the time from making fun of it.

Stuart Kings and Benevolences: 1614–1633

After benevolences were used less during Elizabeth's reign, they were not asked for again until near the end of James I's rule. Facing a difficult Parliament that wouldn't agree to his requests, James I brought back the practice in 1614. He had already received large donations from church leaders, showing that his wealthy subjects were ready to support him. Letters were sent out explaining how compassionate (caring) those were who had given money voluntarily to the king when Parliament wasn't raising taxes. These letters invited other gentlemen to do the same.

Only two months later, more urgent letters were sent. These described the defeat of many of England's allies in Europe. They stressed the need for contributions to the king's military fund. The benevolence faced some protests but eventually raised about £65,000. This was thanks to the support of these well-off subjects.

In 1620, James announced he would militarily support Frederick V of the Palatinate, who had recently been overthrown. However, it was clear the royal treasury was empty and couldn't pay for such a military action. So, James introduced another benevolence in February of that year. The cause of Frederick had become very popular in England. People saw it as protecting Protestantism in Europe. Many important figures made large contributions. The future king, Charles, promised to pay £10,000. Each great lord was asked for £1,000. The Secretary of State, Robert Naunton, promised to give £200 a year until the war ended.

The amount collected was apparently not enough for the king. He asked for another contribution in October and November. But an expected drop in corn prices meant many of the kingdom's wealthiest people were unwilling to give as much as they had before. In total, despite this apparent public support, James received only £30,000. This was less than half of what he had earned previously. So, he was forced to call the Parliament of 1621 to raise taxes.

However, once this Parliament was dismissed, James imposed another benevolence in early 1622. This faced opposition. One document from the time reported that people opposed it not only because they were poor but also because Parliament had previously abolished benevolences, which they still believed in. Despite this, it managed to bring in over £116,000 in total. This was almost as much as Parliament had raised the previous year.

After this, no more benevolences were collected. However, they were suggested two more times near the end of James' reign, in 1622 and 1625. In 1633, Charles I allowed a diplomat to collect a benevolence for Frederick V's recently widowed wife, Elizabeth Stuart. But a disagreement between the diplomat and one of the king's relatives caused the plans to be stopped.

Images for kids

-

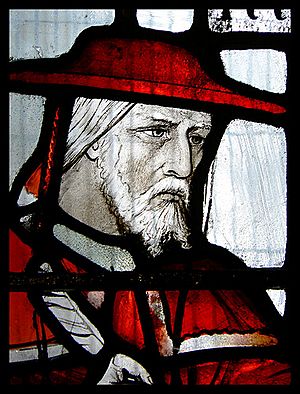

Edward IV (ruled 1461–1483) was the first English king to ask for benevolences.

-

Cardinal John Morton was known for an argument used to collect Henry VII's first benevolence. It was called Morton's Fork.

-

Elizabeth I (ruled 1558–1603) used benevolences less often than earlier kings. She only asked for a few in the 1580s and 1590s.

-

James I (ruled 1603–1625) brought back the practice of benevolences in 1614.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |