Bevin Boys facts for kids

The Bevin Boys were young British men who were chosen to work in coal mines during and after World War II. This happened between December 1943 and March 1948. Their job was to help produce more coal, which was very important for the war effort. Coal was needed to power ships, trains, and to make electricity.

The program was named after Ernest Bevin, a politician who was in charge of Labour and National Service during the war. About 48,000 Bevin Boys, aged 18–25, were chosen by a special lottery. They did important and often dangerous work in the mines. Even though the war ended in May 1945, the last Bevin Boys finished their service in March 1948. Most of them did not stay in mining after the war.

Many people didn't understand why these young men weren't fighting in the military. They sometimes thought Bevin Boys were avoiding the war, which wasn't true. Police would often stop them, thinking they might be deserters. Unlike soldiers, Bevin Boys did not get medals for their service until 1995, many years later.

Contents

Why the Bevin Boys Program Started

Not Enough Coal for the War

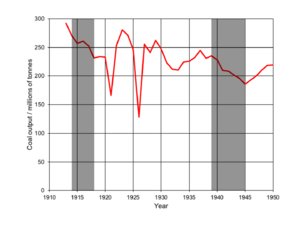

When World War II began in September 1939, Britain needed a lot of coal. It was the main fuel for ships, trains, and power plants. But coal production had started to drop.

At the start of the war, the government sent many young, strong coal miners to join the armed forces. By mid-1943, the mines had lost 36,000 workers. These workers were not replaced because other young men were also joining the military.

Miners also went on strike sometimes because of disagreements over pay. This also reduced the amount of coal being produced. To help, the government increased the minimum pay for miners and created a new department called the Ministry of Fuel, Light and Power. This ministry was in charge of making sure enough coal was produced for the war.

By October 1943, Britain was in urgent need of more coal. It was essential for factories making war supplies and for heating homes during winter.

Asking for Volunteers

On June 23, 1941, Ernest Bevin asked former miners to come back to work in the pits. He hoped to get 50,000 more miners. He also stopped more miners from being called up for military service.

Later, on November 12, 1943, Bevin spoke on the radio to high school students. He encouraged them to volunteer to work in the mines instead of joining the military. He promised they would get help for further education, just like those who served in the armed forces.

We need 720,000 men continuously employed in this industry... This is where you boys come in. Each one of you, I am sure, is full of enthusiasm to win this war. You are looking forward to the day when you can play your part with your friends and brothers who are in the Navy, the Army, the Air Force... But believe me, our fighting men will not be able to achieve their purpose unless we get an adequate supply of coal... So when you go to register and the question is put to you "Will you go into the mines?" let your answer be, "Yes, I will go anywhere to help win this war".

—Ernest Bevin, 12 November 1943

The name 'Bevin Boys' likely came from this radio speech.

Starting Conscription

On October 12, 1943, the Minister of Fuel and Power, Gwilym Lloyd George, announced that some young men would be sent to work in the mines. On December 2, Ernest Bevin explained the plan in more detail. He said they planned to send 30,000 men aged 18 to 25 to the mines by April 1944.

From 1943 to 1945, one out of every ten young men called up for national service was sent to the mines. This made many young men upset because they wanted to join the fighting forces. They felt their work as miners would not be seen as important.

The first Bevin Boys started their mining work on February 14, 1944, after finishing their training.

How the Program Worked

Choosing the Miners

To make the choice fair, one of Bevin's secretaries would pick a number from 0 to 9 each week. Any young man whose National Service registration number ended in that digit was sent to work in the mines. The only exceptions were those chosen for highly skilled war jobs, like flying planes, or those who were not physically fit for mining. Bevin Boys came from all kinds of backgrounds, from office jobs to heavy labor.

There was a way for conscripts to challenge the decision, but it was rare for it to be changed. If someone refused to work in the mines, they could be sent to prison. By May 1944, 285 young men had refused, and 135 were taken to court. Some were even sent to prison.

Training for the Mines

Young men who were almost 18 years old received a postcard telling them to report to a training center.

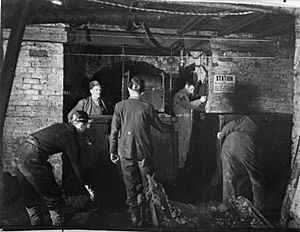

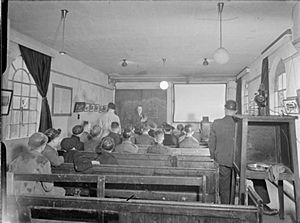

Bevin Boys who had never worked in a mine before received six weeks of training. Four weeks were in a classroom, and two weeks were at the mine they would be working in. For their first four weeks underground, an experienced miner watched over them. Most Bevin Boys did not cut coal directly. Instead, they helped by filling tubs or wagons and moving them to the shaft to be taken to the surface. They were given helmets and safety boots with steel toes.

Pay and Working Conditions

When the first Bevin Boys started training, there were complaints about their pay. An 18-year-old earned 44 shillings per week, which was barely enough to live on. Some even went on strike. Experienced miners also complained because a new 21-year-old recruit earned the same minimum wage as they did.

Bevin Boys did not wear uniforms or badges. They wore their oldest clothes. Because they were of military age and had no uniform, police often stopped them. They were questioned about avoiding military service.

How People Saw the Bevin Boys

Many Bevin Boys were teased because they didn't wear a uniform. Some people wrongly accused them of trying to avoid joining the military. Also, some people who refused to fight in the war for personal beliefs (called "conscientious objectors") were sent to work in the mines. This was a different program, but sometimes people confused the Bevin Boys with them. This led to unfair treatment.

In 1943, Ernest Bevin said in Parliament:

There are thousands of cases in which conscientious objectors, although they have refused to take up arms, have shown as much courage as anyone else in Civil Defence and in other walks of life.

—Ernest Bevin, 9 December 1943

The Program Ends

The last time young men were chosen for the Bevin Boys program was in May 1945, just before Victory in Europe Day (VE Day). However, the very last Bevin Boys were not released from their service until March 1948.

Recognizing Their Contribution

Soon after the Bevin Boys started work, people began asking for a special badge to recognize their important national service.

After the war, Bevin Boys did not receive medals. They also did not have the right to get their old jobs back, unlike some soldiers. However, they could get help from the government to pay for university fees and living costs if they wanted to study further.

The important role the Bevin Boys played in Britain's war effort was not fully recognized until 1995. This was 50 years after VE Day, when Queen Elizabeth II mentioned them in a speech.

On June 20, 2007, Prime Minister Tony Blair announced that thousands of conscripts who worked in mines during WWII would receive a special veterans badge. This badge was similar to the one given to armed forces members. The first badges were given out on March 25, 2008, by Prime Minister Gordon Brown. This marked 60 years since the last Bevin Boys finished their service.

On May 7, 2013, a memorial for the Bevin Boys was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum in Alrewas, Staffordshire. The memorial looks like the Bevin Boys Badge. It was designed by a former Bevin Boy named Harry Parkes. It is made of four stone pillars that are expected to turn black over time, just like coal.

The Bevin Boys Association is still trying to find all 48,000 Bevin Boys who served in Britain's coal mines.

Famous Bevin Boys

Some well-known people who were Bevin Boys include:

- Peter Archer, a lawyer and politician

- Stanley Baxter, an actor

- John Comer, an actor

- Eric Morecambe, a famous comedian

- Nat Lofthouse, a footballer

- Brian Rix, an actor and charity leader

- Peter Shaffer, a writer for plays

Bevin Boys Association

The Bevin Boys Association started in 1989 with 32 members. By 2009, it had grown to over 1,800 members from all over the UK and other countries. The association continues to hold meetings and reunions. They also attend events to remember the Bevin Boys' service.

See also

- Unfree labour – This is a different idea. Work done during a war or national emergency, like by the Bevin Boys, is not considered "unfree labour."

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |