Bonneville Speedway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Bonneville Salt Flats Race Track

|

|

A Phoenix diesel truck racing at Bonneville in August 2003

|

|

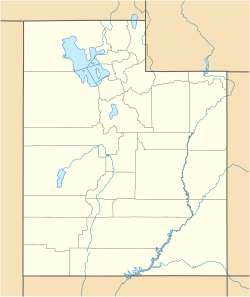

| Nearest city | Wendover, Utah |

|---|---|

| Area | 36,650 acres (14,830 ha) |

| Built | 1911 |

| NRHP reference No. | 75001826 |

| Added to NRHP | March 16, 1984 |

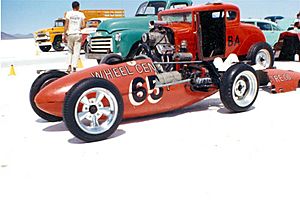

The Bonneville Speedway is a famous racing area located on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Wendover, Utah. It's a huge, flat, white desert made of salt, known worldwide as the perfect place for setting amazing land speed records. Imagine cars, motorcycles, and even special vehicles going incredibly fast! The Bonneville Salt Flats Race Track is so special that it's listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

People first started racing here in 1912. But it became really popular in the 1930s when famous racers like Ab Jenkins and Sir Malcolm Campbell came to try and break speed records.

Sadly, the racing surface has gotten smaller and the salt layer thinner over the years. This has sometimes led to races being cancelled, like Speed Week in 2014 and 2015. Today, the main racing area is much shorter than the long tracks racers used to enjoy.

Contents

How the Race Tracks Are Made

Every summer, special teams get the Bonneville Speedway ready for racing. In the past, the Utah Department of Transportation would mark out the tracks. They used to make two main tracks: a straight one about 10-mile (16 km) long for speed tests, and a big oval track for longer distance races. The oval track could be 10 and 12 miles (16 and 19 km) long, depending on how good the salt surface was.

Since the 1990s, the groups that organize the races have taken over track preparation. Weeks before an event, they find the best spot on the flats. Then, they smooth out the tracks. Experts use special tools to measure the exact distances for timing the vehicles. The day before racing starts, they put out flags and cones to mark the track edges.

Long ago, a thick black line was painted down the middle of the straight track. But this line wore away too fast. So, they started painting lines along both sides instead. Now, painting lines is very expensive. Most events use flags and cones to mark the tracks. The last time black lines were used was for Speed Week in August 2009.

The number of tracks and how they are timed can change for each event. Big events like Speed Week might have up to four tracks. They often time speeds over several miles, usually from the second mile to the fifth mile. Smaller events, often for world record attempts, might use just one track. This track would have one timed mile and one timed kilometer in the middle. Extra markers and cones show where the track ends and where the timing equipment is.

Why the Salt Flats Are Changing

The Bonneville Salt Flats are facing some challenges. Speed Week, a major annual race, was cancelled in both 2014 and 2015. Many other speed racing events were also called off. This happened because the track conditions were not good enough.

Heavy rains caused mud from the nearby mountains to wash onto the flats. This mud covered about 6 mi (9.7 km) of the racing track. Usually, racers could use another part of the flats. However, nearby salt mining has made this alternative area much smaller.

The salt layer itself has also been getting thinner. In the 1940s and 50s, the salt crust was as thick as 3 ft (0.91 m). By 2015, it was only about 2 in (0.051 m) deep. Scientists think the salt might be dissolving into underground saltwater.

Experts have been studying these changes since the 1960s. The exact reasons are still not fully clear. But it seems to be a mix of local weather changes and the salt mining operations. Some ideas, like pumping salt back onto the flats, have been tried but haven't worked yet.

Exciting Racing Events

Many exciting events happen at the Bonneville Speedway each year.

In August, the Southern California Timing Association and Bonneville Nationals Inc. put on Speed Week. This is the biggest event of the year. Hundreds of drivers come to compete and try to set the fastest speeds in many different vehicle types. Speed Week has been a tradition since 1949.

Later in August, the Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials take place. This event is all about motorcycles trying to go as fast as possible.

In September, the Utah Salt Flats Racing Association (USFRA) hosts the World of Speed. This event is similar to Speed Week. The USFRA also has a "Test-n-Tune" event earlier in the summer. This allows racers to practice before the main competition.

In October, the Southern California Timing Association holds the World Finals. This is a smaller version of Speed Week. The weather is usually cooler, and the salt surface is often drier. This event attracts serious racers. It's their last chance to break a land speed record and get their name in the SCTA record book for that year.

Besides these big public events, there are usually a few private races each year. These are not widely advertised but are still important for testing and setting records.

Amazing Land Speed Records

The Bonneville Speedway is famous for the many land speed records set there. These records are for the fastest speeds ever achieved by vehicles on land.

In 1960, Mickey Thompson became the first American to go faster than 400 miles per hour (640 km/h). He reached 406.60 miles per hour (654.36 km/h)! This beat John Cobb's record from 1947.

Many other incredible records have been set. Here are a few examples:

- 1935: Sir Malcolm Campbell reached 301.129 miles per hour (484.620 km/h) in his Blue Bird car.

- 1963: Craig Breedlove hit 407.447 miles per hour (655.722 km/h) in his Spirit of America.

- 1965: Craig Breedlove pushed even further, reaching 600.601 miles per hour (966.574 km/h) in Spirit of America — Sonic 1.

- 1967: Burt Munro set a motorcycle record of 184.037 miles per hour (296.179 km/h) on his Indian Scout V-Twin.

- 1970: Gary Gabelich achieved an amazing 622.407 miles per hour (1,001.667 km/h) in his rocket-powered Blue Flame.

- 2006: Andy Green set the "World's Fastest Diesel" record at 350.092 miles per hour (563.418 km/h) in the JCB Dieselmax.

- 2008: Karlee Cobb became the youngest person at the time to hold a land speed record, reaching 109.867 miles per hour (176.814 km/h) on a Buell Blast motorcycle.

- 2016: Roger Schroer drove the Venturi Buckeye Bullet 3, the fastest electric vehicle, at 341.4 miles per hour (549.4 km/h).

- 2018: Shigeru Yamashita set a record of 209.442 miles per hour (337.064 km/h) on a Kawasaki Ninja H2, making it the fastest street-legal production motorcycle.

- 2020: George Poteet reached 470.733 miles per hour (757.571 km/h) in his Speed Demon 715 streamliner.

Bicycle Speed Records

It's not just cars and motorcycles that set records at Bonneville! Cyclists have also tried to achieve incredible speeds. They often do this by riding behind a special vehicle with a large shield. This shield helps block the wind, allowing the cyclist to go much faster.

- In 1985, American cyclist John Howard set a world record of 244 km/h (152 mph).

- On October 15, 1995, Dutch cyclist Fred Rompelberg reached 268.831 km/h (167.044 mph).

- In 2016, Denise Mueller-Korenek set a women's bicycle land speed record at 147 mph (237 km/h). John Howard, the previous record holder, coached her!

- In 2018, Mueller-Korenek broke her own record and the men's record. She reached an amazing speed of 183.9 miles per hour (296.0 km/h)!

See Also

- Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials (BMST)

- Black Rock Desert

- Land speed record

- List of vehicle speed records

- The World's Fastest Indian - a movie about a man who raced at Bonneville.

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Tooele County, Utah

External Links

- Speed Record Club

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |