William M. Tweed facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William M. Tweed

|

|

|---|---|

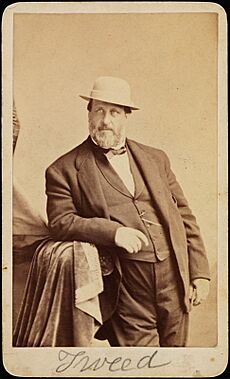

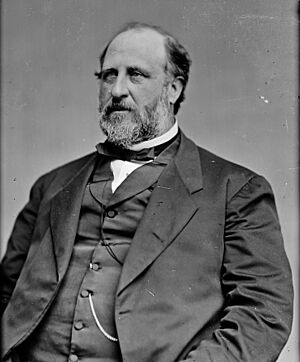

Tweed in 1870

|

|

| Member of the New York Senate from the 4th district |

|

| In office January 1, 1868 – December 31, 1873 |

|

| Preceded by | George Briggs |

| Succeeded by | John Fox |

| Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall | |

| In office 1858–1871 |

|

| Preceded by | Fernando Wood |

| Succeeded by | John Kelly and John Morrissey |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 5th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 |

|

| Preceded by | George Briggs |

| Succeeded by | Thomas R. Whitney |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Magear Tweed

April 3, 1823 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | April 12, 1878 (aged 55) New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Jane Skaden

(m. 1844) |

| Profession | Bookkeeper, businessman, political boss |

William Magear "Boss" Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878) was an American politician. He is best known for being the powerful leader of Tammany Hall. This was a political group linked to the Democratic Party in New York City during the 1800s.

Tweed had a lot of power and influence. He was one of the biggest landowners in New York City. He also held important positions in many companies, like the Erie Railroad and the Brooklyn Bridge Company.

He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1852. In 1858, he became the head of Tammany Hall. He was also elected to the New York State Senate in 1867. Tweed's biggest power came from controlling jobs and projects in New York City. This helped him gain loyalty from many voters.

Tweed was found responsible for taking a lot of money from New York City taxpayers. Estimates of the amount stolen range from $25 million to $200 million. He was sent to jail but escaped once. He was caught again and died in prison.

Contents

Early Life and Start in Politics

Tweed was born on April 3, 1823, in New York City. His family had Scottish roots. His father was a chair-maker. Tweed left school at age 11 to learn his father's trade. He also worked as a bookkeeper and brushmaker. In 1844, he married Mary Jane C. Skaden.

Tweed joined a volunteer fire company called Americus Fire Company No. 6. It was also known as the "Big Six." This group used a snarling red Bengal tiger as its symbol. This tiger became a symbol for Tweed and Tammany Hall for many years. Volunteer fire companies were important for politics back then. Tweed's actions caught the attention of Democratic politicians.

In 1850, Tweed ran for Alderman, a city council position. He lost that election but won the next year. This was his first political job. He then became connected with a group of aldermen known for their dishonest actions.

In 1852, Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives. His time there was not very special. In 1858, he was appointed to the New York County Board of Supervisors. This board became his first way to make a lot of money dishonestly. Tweed and others on the board forced businesses to pay extra money to work with the city.

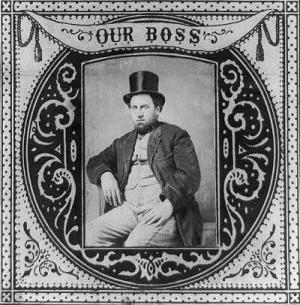

Tweed opened a law office, even though he was not a trained lawyer. He became the head of Tammany Hall in 1863. He was then called "Boss." He made his power stronger by creating a small group to run the club.

Tweed found ways to increase his income. He used his law firm to get money, pretending it was for legal work. He also bought the New-York Printing Company, which became the city's official printer. This company and others he owned overcharged the city government for goods and services. He also became one of the biggest landowners in the city.

He started a group called the "Tweed Ring." He helped his friends get elected to important city jobs. This included the City Comptroller and District Attorney. These friends helped him control city money and projects.

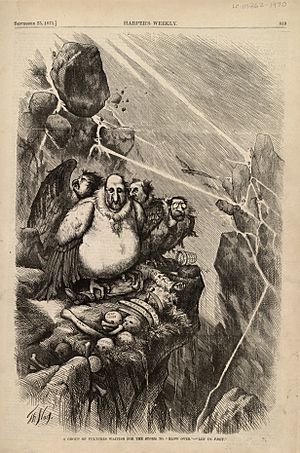

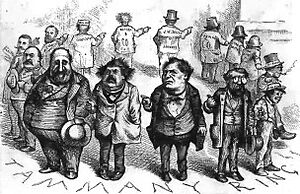

Tweed began to show off his wealth. He wore a large diamond on his shirt. This became a famous detail in cartoons by Thomas Nast. Nast's cartoons in Harper's Weekly often criticized Tweed. Tweed also bought a fancy house in a fashionable part of New York City.

Tweed was involved in early professional baseball. He helped the New York Mutuals team. He is even credited with starting the idea of "spring training" in 1869.

From 1868 to 1873, Tweed was a member of the New York State Senate. He helped powerful financiers take control of the Erie Railroad. In return, Tweed received a large amount of stock and became a director of the company.

City Corruption and Control

After the 1869 election, Tweed gained even more control over New York City's government. A new city charter was passed in 1870. This charter put control of the city's money in the hands of a Board of Audit. This board included Tweed, the Mayor, and the City Comptroller, all of whom were Tammany men.

This gave the Tweed Ring very strong control over the city. They used this power to take money from taxpayers. Contractors working for the city, who were friends of the Ring, would greatly increase their bills. These inflated bills would then be paid by the city. The extra money was then divided among Tweed and his associates.

For example, the cost to build the Tweed Courthouse grew to nearly $13 million. This was almost twice the cost of the Alaska Purchase! A carpenter was paid over $360,000 for one month's work in a building with little woodwork. A plasterer received over $133,000 for just two days of work. Tweed even bought a marble quarry to supply marble for the courthouse at a huge profit for himself.

Tweed and his friends also made large profits from developing areas like the Upper East Side. They would buy undeveloped land. Then, they would use city resources to improve the area, like adding water pipes. This made the land much more valuable, and they would sell it for a big profit.

Despite the dishonest actions, Tweed and Tammany Hall did help develop parts of upper Manhattan. However, this came at a high cost, tripling the city's debt.

Tweed also played a role in the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. To ensure the project moved forward, money was paid to city officials. Tweed and two others from Tammany received a large share of the Bridge Company's private stock. This meant they had control over the project, even though the cities of Brooklyn and Manhattan paid most of the costs.

By 1871, Tweed was on the board of many important companies. He was also president of the Guardian Savings Bank. He and his partners even set up the Tenth National Bank to better manage their money.

Arrest, Escape, and Final Days

Tweed was arrested but released on $1 million bail. He was re-elected to the state senate in November 1871. However, Tammany Hall did not do well in general elections. Members of the Tweed Ring began to leave the country.

Tweed was arrested again. He was forced to leave his city jobs and was replaced as Tammany's leader. He was released on bail again, this time for $8 million.

Tweed's first trial in 1873 ended with no verdict. His second trial in November led to convictions on many counts. He was fined and sentenced to prison. A higher court later reduced his sentence to one year.

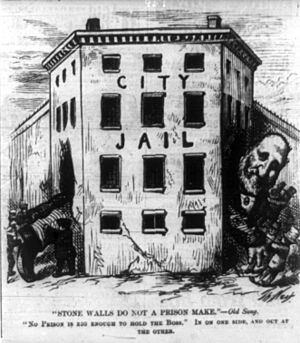

After his release, New York State sued Tweed to get back $6 million in stolen money. He could not pay the $3 million bail and was sent to the Ludlow Street Jail. During a home visit on December 4, 1875, Tweed escaped. He fled to Spain and worked as a sailor.

The U.S. government found him. He was recognized from Nast's political cartoons. He was returned to New York City on November 23, 1876, and put back in prison.

Tweed was desperate. He agreed to tell a special committee about the Tweed Ring's operations in exchange for his release. However, the governor of New York refused to honor the agreement. Tweed remained in jail.

He died in the Ludlow Street Jail on April 12, 1878, from severe pneumonia. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. The mayor did not allow the flag at City Hall to be flown at half-mast.

Understanding Tweed's Legacy

Historians have different views on William Tweed. Many focus on the dishonesty and how he and his friends took money from the city. They believe his actions were very wrong and overshadow any good he might have done.

However, some historians argue that Tweed was also a modernizer. He helped improve city management. Much of the money he took from the city treasury went to people in need. He provided free food at Christmas and jobs on city projects. This helped him gain support from his voters.

As a politician, Tweed worked to expand welfare programs. He supported private charities, schools, and hospitals. He also fought for state funding for Catholic schools and hospitals. Under Tweed's influence, New York State spent more on charities in a few years than in the previous decade and a half combined.

During Tweed's time, Broadway was widened. Land was secured for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Upper East Side and Upper West Side were developed with necessary services. These projects benefited the city, even if they also benefited the Tweed Ring.

Some historians believe that the negative image of Tweed was partly created by newspapers like Harper's Weekly and The New York Times. These papers had ties to the Republican party and may have used the campaign against Tweed to distract from other political issues.

Tweed himself did not want a statue built in his honor while he was alive. He said, "Statues are not erected to living men." Today, Tweed is often seen as the classic example of a powerful, dishonest city boss.

Tweed's Middle Name

Tweed always signed his middle name as "M." People often mistakenly thought his middle name was "Marcy." His real middle name was Magear, which was his mother's maiden name. The confusion came from a cartoon by Thomas Nast that included a quote from William L. Marcy, a former governor.

Images for kids

-

A Group of Vultures Waiting for the Storm to "Blow Over"—"Let Us Prey." by Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly newspaper, September 23, 1871. "Boss" Tweed and members of his ring, Peter B. Sweeny, Richard B. Connolly, and A. Oakey Hall, weathering a violent storm on a ledge with the picked-over remains of New York City.

-

Thomas Nast depicts Tweed in Harper's Weekly (October 21, 1871)

-

Nast depicts the Tweed Ring: "Who stole the people's money?" / "'Twas him." From left to right: William Tweed, Peter B. Sweeny, Richard B. Connolly, and Oakey Hall. To the left of Tweed in the background are James H. Ingersoll and Andrew Garvey, city contractors involved with much of the city construction.

-

"Stone Walls Do Not a Prison Make": Editorial cartoon by Thomas Nast predicting Tweed could not be kept behind bars (Harper's Weekly, January 6, 1872)

See also

- Elbert A. Woodward

- Timothy "Big Tim" Sullivan

- Tweed law

- William J. Sharkey (murderer)