Tweed Courthouse facts for kids

|

Old New York County Courthouse

|

|

The entry portico in 2010

|

|

| Location | 52 Chambers Street, Manhattan, New York, United States |

|---|---|

| Built | 1861–72 1877–81 |

| Architect | John Kellum, Leopold Eidlitz |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001277 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | September 25, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | May 11, 1976 |

The Tweed Courthouse (also called the Old New York County Courthouse) is a famous building in New York City. It is located at 52 Chambers Street in Civic Center, Manhattan. The building was designed in the Italianate style, which was popular in the mid-1800s. Its inside has a different look, called Romanesque Revival.

A powerful and dishonest leader named William M. "Boss" Tweed was in charge when the courthouse was built. He led a group called Tammany Hall, which controlled New York's government. Tweed used the building's construction to secretly take large amounts of money.

The Tweed Courthouse was used as a court building for New York County. It is the second oldest government building in Manhattan, right after City Hall.

The building has a main part with two side sections. A back wing was added later. Architect John Kellum designed the first part, built from 1861 to 1872. Work stopped in 1871 when Kellum died and the public found out about the money problems. Architect Leopold Eidlitz finished the building between 1877 and 1881. He added the back wing and completed the inside.

Newspapers often criticized the project for being too expensive. For many years, people even wanted to tear it down. The building was fixed up and made beautiful again in 2001. Today, it is home to the New York City Department of Education's main offices and some schools. The Tweed Courthouse is a National Historic Landmark, which means it's a very important historical site. Its outside and inside are also protected as New York City landmarks.

Contents

Location of the Tweed Courthouse

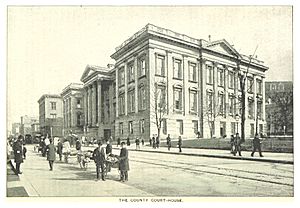

The Tweed Courthouse is in the Civic Center area of Manhattan. It sits in the northern part of City Hall Park, just north of New York City Hall. The building is bordered by Chambers Street to the north, Centre Street to the east, and Broadway to the west.

The courthouse is about 258 feet long and 149 feet wide. The park around it has shady paths and green lawns. Across Chambers Street, you can see other famous buildings like the Surrogate's Courthouse. The Manhattan Municipal Building is across Centre Street.

How the Courthouse Looks

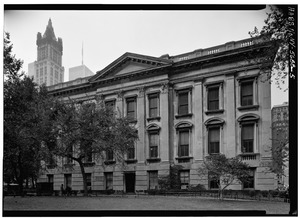

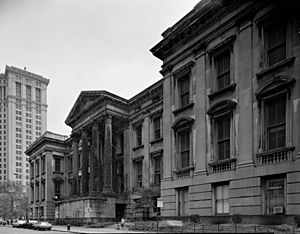

The Tweed Courthouse has a main part, two side sections, and a back wing. It is four and a half stories tall. This includes a small attic floor. The first floor is at ground level. The building sits on a low base made of granite.

The roof has been replaced three times. It was first iron, then asphalt, and now it's stainless steel and rubber. Experts say the building has "some of the finest mid-19th century interiors in New York."

Main Building Design

The first two side sections were designed by John Kellum. They were shaped like an "I". The main entrance on Chambers Street has a large porch with columns. This porch rises three and a half stories high. The outside walls are made of brick, covered with panels of granite and marble. The bottom part of the building has rough-cut stone.

Kellum designed the main part of the building in the style of a Renaissance palazzo. This is also called the "Anglo-Italianate" style. It was inspired by the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. The courthouse was meant to have a grand entrance with a large staircase and tall columns. It also had a basement with rough stone, fancy window tops, and columns between the windows. The original plan included a large iron dome, but it was never built.

Outside Walls

The main entrance is on Chambers Street, on the north side of the building. It has a large porch with four tall columns. These columns cover a section with three windows. Big wooden doors are on the second floor. The third floor has three windows.

A large granite stairway leads up to the porch. This stairway was removed in the mid-1900s to widen the street, but it was put back in 2002.

On each side of the northern wall, there are three windows per floor. This gives the northern side a total of fifteen windows on each level. All the windows have their original decorations. Each window has a decorative top and a sill below it. The windows on the side sections are even more decorated. The second and third-floor windows can be opened from both the top and bottom. The ground-floor windows are simpler. A decorative band goes around the top of the northern, western, and eastern walls.

The western and eastern sides of the building look the same. Each has three sections with three windows per floor, making nine windows on each level. The middle section on these sides has a simpler triangular top than the northern side. The wooden doors on the ground floor are simpler than the main entrance doors. The southern side looks like the northern side, but its middle section was finished later.

Southern Wing

The four-story southern wing was built in the Romanesque Revival style by architect Leopold Eidlitz. This part of the building sticks out about 48 feet to the south, towards City Hall. Kellum had planned a porch for this wing, but Eidlitz did not include it.

The outside of the southern wing has three windows across and three windows deep. It is made of stone that is similar in color to the rest of the building. The ground floor has three arched windows on the sides. The second and fourth floors have arched windows, while the third floor has decorative bands. Columns separate the windows on the third and fourth floors.

Inside the Courthouse

The inside of the Tweed Courthouse is very grand. The most important part is a large central rotunda. Many rooms have cast-iron baseboards and fancy steel lights. The ceilings in many rooms are 28 feet tall.

Rotunda

The center of the courthouse is an eight-sided rotunda, about 53 feet wide. It has brick walls with arches, cast-iron, and stone decorations. Balconies with iron railings stick out into the rotunda from the second and third floors. The rotunda mixes Kellum's and Eidlitz's styles. Kellum used classic cast iron and plaster. Eidlitz used medieval-style brick and stone. Most of the rotunda shows Eidlitz's design.

A skylight is at the top of the 85-foot-high rotunda. The original stained-glass skylight was removed in the 1940s. A new one was put in in 2001.

The four floors around the rotunda have a similar layout. Staircases or open areas are in the middle, and the old courtrooms (now offices) are along the outside. The areas to the west and east of the rotunda are the same on both sides. The ground floor has been changed several times, but the rotunda and stair halls are still in their original design. The rotunda floor is made of iron, marble, and glass. The rest of the ground floor has marble tiles and plaster ceilings. There are several hallways. Doors made of walnut wood lead to the rooms.

The second floor has the main entrance from the Chambers Street staircase. Inside the rotunda, there is a cast-iron ceiling and a marble-and-glass floor. The stair halls are just outside the rotunda. They have marble floors and plaster walls and ceilings. Like the ground floor, there are main hallways and smaller side halls.

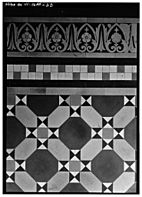

The second floor has four main rooms. One room, 201–2, is on the south side. It has a medieval design with colorful tile floors, stone arches, and a stone ceiling. It also has oak double doors with glass panels showing the seal of New York City. This room also has granite columns, stone columns, a stone fireplace, and iron heaters under the windows. There is also a small mezzanine floor above the second floor.

The third floor is similar to the first and second floors. The rotunda floor is marble tile. The rotunda has red, tan, and black brick patterns. The third floor is the top floor for the two main staircases from the rotunda. Four more stairs lead to the fourth floor. Another mezzanine is above the third floor.

The fourth floor has a similar layout. It has marble floors, plaster walls and ceilings, and corner stairs from the third floor. Stairs go up to the attic. The attic has a concrete and wood floor. It also holds the structures that support the roof and the rotunda's skylight.

Stairs and Elevators

Next to the rotunda, there are two cast iron staircases. They connect the first, second, and third floors. These staircases are mirror images of each other. Each one has a wide stairway that goes up to a small landing, then splits into two smaller stairways. The railings have fancy iron posts with lampposts on top. The stairs also have rectangular panels with circles underneath. The top parts of the stairs used to be lit by glass skylights. The iron handrails were painted to look like wood.

The third and fourth floors are connected by four staircases, one in each corner. Three of these stairs have fluted iron railings and used to have skylights. The fancy staircase in the southwest corner was replaced with a plain steel one when elevators were put in around 1910.

Between 1911 and 1913, two elevators were added on the southwest side. At first, the elevator cars were open cages. This meant people could touch the walls as the elevator moved! In 1992, the elevators were updated with glass walls and automatic controls. Before that, they were the last manually operated elevators in a New York City government building.

Architects of the Courthouse

John Kellum started as a house carpenter. He later formed a company that designed commercial buildings. Kellum began his own practice in 1860. He was hired for the Tweed Courthouse project in August 1861. He died in August 1871, around the time the "Tweed ring" lost its power.

Thomas Little was also involved in the design. He was a political appointee. Some records suggest Little might have been the first architect, and Kellum was hired later.

Leopold Eidlitz was born in Prague and came to the U.S. in 1843. He worked on churches and other important buildings like the New York State Capitol. In 1876, Eidlitz was hired to finish the courthouse. He added the building's south wing and the rotunda's dome-like skylight. Eidlitz believed that the building's materials were the most important part of its design. His Romanesque style, using a lot of brick and stone, changed how the courthouse looked.

History of the Courthouse

The Tweed Courthouse is the second oldest government building in Manhattan. In the 1600s, the land was used as public grazing areas. Later, it became a place for prisoners and a burial ground. Eight graves from the colonial era are still under the courthouse. Other government buildings were also on the site over time.

In the 1850s, New York City was growing fast. New buildings were needed around City Hall. Several courthouses had burned down in 1854. In 1858, a plan was approved to build a new courthouse north of City Hall. It would hold several courts and offices. The first plans for the building were submitted in 1859. Construction was approved in 1859. The land for the courthouse was valued at $450,000 in 1861.

"Boss" Tweed's Construction

From 1861 to 1871, William M. Tweed, known as "Boss" Tweed, was a very powerful politician. He was in charge of building the New York County Courthouse. He used this position to steal millions of dollars. Tweed was one of the most dishonest politicians in U.S. history. He and his political friends stole up to $300 million.

One way they stole money was by making the construction very slow. The historian Alexander Callow called this corruption "a classic in the history of American graft."

Construction began on September 16, 1861. Tweed bought a marble quarry to supply marble for the courthouse. This allowed him to make a huge profit for himself. Work on the courthouse also slowed down because of the American Civil War. In 1865, a reporter for The New York Times said that the outside was mostly done, but the inside was not. The reporter worried about the rising costs and delays. The New York County Court of Appeals moved into the building in March 1867, even though it was still unfinished.

In the first four years, the supervisors took 65 percent of the money from each contract. In 1866, Supervisor Smith Ely Jr. first claimed that money was being wasted. He said that "grossly extravagant and improper expenditures" were made. For example, a $350,000 bill was paid for carpeting. This was enough carpet to cover City Hall Park three times! Yet, some offices still had no carpets years later. In another case, a contractor was paid $133,180 for two days of work on window frames. About $1.3 million was spent on plaster in two years. A set of three tables and forty chairs cost the city $179,729.60.

In 1870, four new officials were put in charge of finishing the courthouse. They were loyal to Tweed. They were given $600,000 by the state. They also decided to use a slate roof instead of a dome. Each official got a 20 percent secret payment from the supply bills.

Few newspapers spoke out against Tweed's corruption, except for The New York Times and cartoonist Thomas Nast from Harper's Weekly. The New York Times published articles in July 1871, showing the huge costs for courthouse materials. Nast's cartoons were aimed at Tweed's supporters. Tweed even offered Nast $500,000 to stop making cartoons, but Nast refused.

The "Tweed ring" was broken up in 1871 when Boss Tweed was arrested. This, along with John Kellum's death, stopped construction for five years. At that time, about $11 million had been spent on the courthouse. But its real value was less than $3 million. The money spent was more than four times the cost of London's Palace of Westminster. Tweed fled the city but was caught and died in jail in 1878.

Finishing the Building

Leopold Eidlitz was hired in 1876 to finish the building. By then, many parts of the courthouse were already being used. Eidlitz was to complete the front porch, the main hall, and the rotunda. He also built a new south wing. Eidlitz changed Kellum's classic interior design to a rich, colorful Romanesque Revival style. He added decorative details like arches to connect the new wing with the rest of the courthouse. His design included a skylight in the rotunda, instead of Kellum's planned dome.

The New York Times criticized the new wing. They called it "cheap and tawdry" compared to the older parts. The American Architect and Building News said the addition was "grafted" onto the original building. They noted that the new Romanesque style clashed with the old Italian style.

The Tweed Courthouse was officially finished in 1881, more than 20 years after work began. The total cost was estimated to be between $11 and $13 million.

Court Use and Changes

After it was finished, the Tweed Courthouse was always linked to William Tweed's crimes. Many people and newspapers saw it in a bad light. A poem called "The House That Tweed Built" was even published in 1871. It made fun of the corruption. However, a guidebook in 1872 described the courtrooms as "large, airy, unobstructed by columns." It wasn't until the 1950s that writers began to appreciate the courthouse for its history.

Because of its bad reputation, city leaders were slow to tear down the building, even when they needed more space. There were many attempts to demolish the courthouse for almost a century. In 1938, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia thought about tearing it down. But the courts inside refused to move. By the 1950s, the courthouse was seen as old-fashioned. Plans were made in 1955 to tear it down. These plans continued until 1974.

Changes were made to the courthouse over time. By 1908, the rotunda's original colors had been painted over with gray. Between 1911 and 1913, elevators were added. The roof was replaced with an iron roof. The original skylight was removed by World War II. The grand steps leading to Chambers Street were removed in the mid-1900s to widen the street. This meant people had to enter through the ground floor.

The building's use also changed. In 1927, the County Court moved out. The City Court then used the building. After 1961, other county offices and the New York Family Court moved in. By the 1980s, it housed city offices. The building became run down, and by 1981, only about fifty people worked there.

By 1974, the city was planning to tear down the courthouse. The cost of a new building was estimated to be $12 million. This was more than renovating the old one. But architectural preservationists opposed the plan. The Tweed Courthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in October 1974. This made it eligible for federal money, but it didn't stop demolition. The plan to destroy it was canceled because of the 1975 New York City financial crisis. The city simply couldn't afford to tear it down or build a new one. In 1984, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission made the building's exterior and interior official city landmarks. This protected it from being changed or torn down without approval.

Saving the Courthouse

In 1978, another report said the courthouse needed $3 million for small repairs or $9 million for a full restoration. The city began restoring each room. The roof was repaired in the late 1970s. The iron roof was replaced with asphalt. The skylight's wooden supports were replaced with cast-iron ones. The inside was repainted, but the outside remained worn. By 1986, after some repairs, 250–300 people worked there.

A major $6.3 million renovation began in 1990. It was supposed to finish by 1994. The city planned a $21 million project to fully restore the building. During this work, architects found serious damage to the front porch and other parts. This caused the Chambers Street entrance to close temporarily. The old, open elevators were updated with glass walls and automatic systems.

The city then planned a full restoration. The cost went from $39 million to $59 million, then to $89 million, as more damage was found.

In May 1999, a company began a complete restoration. They carefully removed up to 18 layers of paint to find the original colors. The skylights and roof over the rotunda were replaced. Marble and glass floors were fixed. New details were carved into the columns. The original ventilation systems were updated with modern heating and cooling. The front steps to Chambers Street were also put back. The restoration was finished in December 2001. After the September 11 attacks happened nearby, the park around the building was closed for security. It reopened in 2007.

The New York Daily News looked into why the renovation cost so much. They found that the original design was very fancy. For example, the outside walls cost $13 million to restore. Reproducing the skylights, stone, and doors cost another $3.2 million. Officials wanted to make it look as close to the original as possible. They even asked for materials from the original companies, which raised costs. Marble for the restoration came from Tweed's old quarry in Massachusetts. Old stone from the building was reused for other parts of the outside.

New York City Department of Education

The building was restored to become the new home for the Museum of the City of New York. But Mayor Michael Bloomberg canceled these plans. Instead, he decided to move the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) into the building. This was to show his focus on education. The building was empty and costing the city $20,000 a month for electricity and security. Most of the building would be offices for the NYCDOE. The ground floor would have classrooms for different schools. A cafeteria in the basement would serve both employees and students. Some NYCDOE employees preferred to stay in their old offices, but others liked the idea of moving to the newly renovated courthouse.

In June 2002, Bloomberg wanted school officials to move in by that fall. The city spent $6.5 million to get the upper floors ready for the NYCDOE. By late 2002, the offices were set up. The building continues to be the NYCDOE's headquarters today.

The ground floor was used as a place for new schools to start. The first was City Hall Academy in 2003. It offered two-week programs for third and seventh graders. City Hall Academy moved out in 2006. Then, a charter school called Ross Global Academy used the space until 2009. The Spruce Street School used the ground floor temporarily until 2011. Another school, Innovate Manhattan Charter School, was there for the 2011–2012 school year. An elementary school, the Peck Slip School, used the ground floor for three years until 2015.

Important Designations

The Tweed Courthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. It was called the "Old New York County Courthouse." Two years later, it was named a National Historic Landmark because of its connection to William Tweed's history. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission made the building's exterior and interior official city landmarks in 1984. They called it "one of the city's grandest and most important civic monuments." The Tweed Courthouse is also part of the African Burial Ground and the Commons Historic District, a city landmark area created in 1993.

See also

In Spanish: Antiguo Palacio de Justicia del Condado de Nueva York para niños

In Spanish: Antiguo Palacio de Justicia del Condado de Nueva York para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |