History of New York City (1946–1977) facts for kids

After World War II, New York City became a very important city worldwide. But after 1950, its population started to shrink. Many people moved to the suburbs, like Levittown. Businesses also left because it was cheaper to operate elsewhere. Crime went up, and the city had to spend a lot on welfare. All these problems led to a big money crisis in the 1970s. The city almost went bankrupt.

Contents

New York After World War II (1940s-1950s)

When many big cities were destroyed after World War II, New York City became very important globally. It became the home of the United Nations headquarters, built between 1947 and 1952. New York also became a major center for art, especially with a style called Abstract Expressionism. It even started to compete with London in international finance and art.

However, the city's population began to drop after 1950. More and more people moved to the suburbs around New York, like the new communities built in Levittown, New York.

In Midtown Manhattan, there was a huge building boom thanks to the good economy after the war. New glass and steel office buildings, in a style called International Style, replaced older buildings. The eastern part of the East Village also changed a lot. Many old apartment buildings were torn down and replaced with large public housing projects. In Lower Manhattan, new building plans started around 1960, led by David Rockefeller with the One Chase Manhattan Plaza building.

Building new things often means tearing down old ones. When the old Pennsylvania Station was destroyed, people became worried about losing historic buildings. This led to the Landmarks Preservation Commission Law in 1965. The city's other famous train station, Grand Central, was also almost torn down but was saved.

Meanwhile, New York City's highway system grew under the leadership of Robert Moses. This led to more traffic jams. But in 1962, community activists led by Jane Jacobs stopped Moses's plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway. This showed that Moses would not have as much power as he used to.

New York in the 1960s

The 1960s brought a slow decline in New York's economy and social life. The city lost its two longtime baseball teams, the Dodgers and the Giants, to California in 1957. A new team, the Mets, was formed in 1962. They played at the Polo Grounds before moving to Shea Stadium in 1964.

A new law, the federal Immigration Act of 1965, changed how people could immigrate to the U.S. This led to more people coming from Asia, which helped create New York's modern Asian American community.

On November 9, 1965, New York experienced a huge power blackout along with much of eastern North America. The city's problems during this blackout were even shown in a 1968 movie. The shift of people to the suburbs after the war caused many traditional industries, like textile manufacturing, to decline in New York. These factories were also very old. With the arrival of container shipping, that industry moved to New Jersey, where there was more space. Blue-collar neighborhoods started to get worse and became centers of crime.

In 1966, the U.S. Navy closed the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which had been operating since the early 1800s. The city bought it, and shipbuilding continued there for another eleven years.

From November 23 to 26, 1966, New York City was covered by a major smog. The air was filled with harmful pollutants. This was the third big smog event in New York City, after similar ones in 1953 and 1963.

Mayor Lindsay's Time

John Lindsay, a Republican, was a very noticeable and popular mayor from 1966 to 1973. New York City became a national hub for protest movements. People protested for civil rights for Black citizens, against the Vietnam War, and for new feminist and gay rights movements.

The city also faced big economic problems as the good times after the war ended. Many factories and entire industries closed down. The population changed a lot, with hundreds of thousands of African-Americans and Puerto Ricans moving in. At the same time, many European-Americans moved out to the suburbs. Labor unions, especially for teachers, transit workers, sanitation workers, and construction workers, had conflicts due to major strikes and racial tensions.

Strikes and Riots in the 1960s

The Transport Workers Union of America (TWU), led by Mike Quill, shut down the city with a complete stop of subway and bus service on Mayor John Lindsay's first day in office. As New Yorkers dealt with the transit strike, Lindsay famously said, "I still think it's a fun city." He walked four miles from his hotel to City Hall to show it. A newspaper columnist, Dick Schaap, then used the sarcastic term "Fun City" to point out that it wasn't.

The transit strike was just the first of many labor problems. In 1968, the teachers' union (the United Federation of Teachers, or UFT) went on strike because several teachers were fired in schools in Ocean Hill and Brownsville.

That same year, 1968, also saw a nine-day sanitation strike. Life in New York became very difficult during this strike. Piles of garbage caught fire, and strong winds blew trash through the streets. With schools closed, police working slowly, firefighters threatening to strike, and the city full of garbage, Lindsay later called the last six months of 1968 "the worst of my public life."

The Stonewall riots were a series of protests against a police raid. They happened in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. These events are often seen as the start of the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world. They showed that people in the gay community were fighting back against unfair treatment.

New York in the 1970s

By 1970, New York City was known for high crime rates and other social problems. A popular song in 1972, "American City Suite," described the decline in the city's quality of life. The city's subway system was seen as unsafe due to crime and often broke down. Homeless people lived in empty, abandoned buildings. The New York City Police Department was investigated for widespread corruption, most famously by police officer Frank Serpico in 1971. In June 1975, a group of labor unions even gave out pamphlets to visitors, warning them to stay away.

However, the opening of the huge World Trade Center complex in 1972 was a bright spot. Planned by David Rockefeller, the Twin Towers were built by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in Lower Manhattan. They became the world's tallest buildings, taking the title from the Empire State Building. But they were soon surpassed by Chicago's Sears Tower in 1973.

New York City's Money Crisis

The U.S. economy struggled in the 1970s, and New York City was hit especially hard. Many middle-class residents moved to the suburbs, which meant less tax money for the city. In February 1975, New York City faced a serious money crisis. Under Mayor Abraham Beame, the city ran out of money for its daily expenses. It couldn't borrow more and was close to not being able to pay its debts, which meant declaring bankruptcy.

The city admitted it had a deficit of at least $600 million, but its total debt was over $11 billion. The city couldn't get loans from banks. There were many reasons for this crisis. The city had guessed it would get more money than it did, didn't save enough for pensions, used money meant for building projects for daily costs, and had poor money management. Also, New York City offered many welfare programs and benefits, including nineteen public hospitals, public transportation, and free higher education. The city government was also slow to deal with labor unions. For example, a "hiring freeze" was announced, but then 13,000 more people were hired in one quarter.

The first idea to fix the problem was the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC). It was set up in June 1975 to manage the city's money and help pay off its huge debts. Felix Rohatyn was its chairman. But the crisis continued to get worse.

The MAC demanded that the city make big changes. These included freezing wages, laying off many workers, raising subway fares, and charging tuition at the City University of New York. The New York State Legislature helped the MAC by changing city sales and stock transfer taxes into state taxes. These taxes then helped secure the MAC bonds. The State of New York also created an Emergency Financial Control Board to watch the city's money. It required the city to balance its budget within three years and follow proper accounting rules. Even with these steps, the value of MAC bonds dropped, and the city struggled to pay its employees. The MAC sold $10 billion in bonds.

When the MAC didn't fix things fast enough, the state came up with a stronger solution: the Emergency Financial Control Board (EFCB). This was a state agency, and city officials had only two votes on its seven-member board. The EFCB took full control of the city's budget. It made big cuts to city services and spending. It cut city jobs, froze salaries, and raised bus and subway fares. Welfare spending was also cut. Some hospitals, branch libraries, and fire stations were closed.

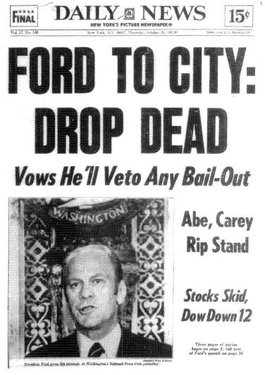

Labor unions helped by using much of their pension funds to buy city bonds. This put their pensions at risk if the city went bankrupt. Mayor Beame had a statement ready to release on October 17, 1975, saying the city couldn't pay its debts. But Albert Shanker, the teachers' union president, finally provided $150 million from the union's pension fund to buy MAC bonds, so the statement was never released. Two weeks later, President Gerald R. Ford made New Yorkers angry by refusing to give the city a bailout.

Ford later signed a bill that gave the city $2.3 billion in federal loans for three years. In return, Congress told the city to charge more for services, cancel a wage increase for city employees, and greatly reduce its workforce.

Rohatyn and the MAC directors convinced banks to delay when the city's bonds were due and to accept less interest. They also convinced city and state employee pension funds to buy MAC bonds to help pay off the city's debts. The city government cut 40,000 employees, delayed agreed-upon wage increases, and kept them below inflation. The loans were paid back with interest.

A mayor focused on careful spending, Democrat Ed Koch, was elected in 1977. By 1977–78, New York City had paid off its short-term debt. By 1985, the city no longer needed the MAC's help, and it closed down.

The 1977 Blackout

The New York City blackout of 1977 happened on July 13 of that year and lasted for 25 hours. During this time, some neighborhoods experienced destruction and looting. Over 3,000 people were arrested, and the city's jails became very crowded.

The money crisis, high crime rates, and damage from the blackouts made many people believe that New York City was in a permanent decline. By the end of the 1970s, nearly a million people had left the city. It would take twenty years for the population to recover. One writer called it a "spiritual crisis" rather than just a "fiscal crisis."

Chronology

| Preceded by History of New York City (1898–1945) |

History of New York City (1946–1977) |

Succeeded by History of New York City (1978–present) |

Images for kids

-

Pennsylvania Station in 1962, two years before it was torn down. This event helped start the historic preservation movement.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva York (1946-1977) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva York (1946-1977) para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |