History of New York City (1898–1945) facts for kids

New York City changed a lot between 1898 and 1945. It became a huge center for communication, trade, and money in the United States. It also became a leader in popular culture and art. By 1920, more than a quarter of the 300 biggest companies in the country had their main offices in New York.

This important time started in 1898 when New York City officially joined its five main areas, called boroughs, into one big city. Back then, about 3.4 million people lived there. New ways to travel, especially the New York City Subway which opened in 1904, helped connect all parts of this growing city. Many new people came from Southern and Eastern Europe, bringing more workers. This immigration slowed down when World War I started in 1914. During the war, there weren't enough workers, so many Black Americans moved north from the Southeast. This big move, called the Great Migration, helped create the Harlem Renaissance, a time when Black artists and writers celebrated their culture.

The 1920s, known as the Roaring Twenties, were a time of excitement and wealth. Many tall buildings, called skyscrapers, were built, making the city's skyline famous. New York's financial area became very important for the country and the world. The city's economy grew steadily after 1896, with only a few small slowdowns. But then, the Great Depression hit, starting with a Wall Street stock market crash in late 1929. The economy got better by 1940 and did very well during World War II. The main parts of the economy were building, shipping, making clothes, tools, and printing. Labor unions also became stronger. New York had the best financial system in the country, many rich people who bought luxury goods, and a thriving art scene thanks to museums, galleries, universities, artists, and writers.

Local political groups, often called "machines," usually controlled politics in the boroughs. However, in 1933, reformers took over. They elected Fiorello La Guardia as mayor, and he was re-elected many times. The federal government helped the city a lot, making it a strong supporter of the New Deal Coalition. This also made New York a good example of how government spending could improve things like roads and buildings.

Contents

New York City's Growth: 1890s–1920s

The five modern boroughs of New York City joined together in 1898. At that time, the cities of New York (which included today's Manhattan and the Bronx) and Brooklyn combined with the mostly rural areas of Queens and Staten Island. The city's population was 3.4 million in 1900. It jumped to 5.6 million by 1920 and reached 7.9 million in 1950. The people living in the city came from many different backgrounds, races, religions, and social classes.

The city grew a lot in terms of people, industries, and wealth. Big projects included building the subway system, which was done by private companies. The city also paid for large new bridges connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn and Queens. These bridges made it easier for people to travel to work and helped industries grow in those areas. New York also improved its port, traffic system, built many new schools, and started big public health programs. Many early skyscrapers, some of the tallest in the world, were built in Manhattan during this time.

Politics and Reformers

New York City's politics often involved fights between political "machines" and reformers. During calm times, the machines had strong support and usually controlled city matters. They also had a big say in the state government. Tammany Hall, a famous Democratic machine, built a strong network of local clubs. These clubs attracted ambitious people from different ethnic groups.

However, during tough times, like the economic problems in the 1890s and 1930s, reformers often took control of important offices, especially the mayor's office. Reformers were not always united. They worked through many different groups, each focusing on its own goals. These groups included educated middle-class men and women, often experts in their fields. They strongly disliked the corruption of the political machines. When the city consolidated in 1898, it gave these reform groups more power, especially when they agreed on a common goal.

There wasn't one single citywide machine. Instead, Democratic machines were strong in each borough, with Tammany Hall in Manhattan being the most well-known. They usually had strong local groups, called "political clubs," and a powerful leader, often called "the boss." Charles Francis Murphy was a very effective but quiet boss of Tammany Hall from 1902 to 1924. Republican groups were much weaker. They often looked to the state or national government for their influence. Seth Low, the president of Columbia University, became the reform mayor in 1901. He wasn't very good at connecting with everyday people and lost support when he tried to stop the alcohol business.

The idea of the Progressive Era influenced New York politics. Reformers wanted to stop waste and corruption. They focused on using experts and scientific methods for big projects. Tammany Hall, under Charles Francis Murphy, even tried to look like a reform group. They supported reformers for mayor and tried to hide obvious corruption. The Irish still controlled Tammany. Leaders found ways to make money, like getting special deals on building projects, without breaking laws.

Three reformers became mayor. Seth Low, a businessman and Columbia University president, won in 1902 with support from reformers and Republicans. Tammany Hall returned in 1904 with George B. McClellan Jr., a respected politician. William Jay Gaynor, a reform judge, won in 1909. John Purroy Mitchel, a favorite of President Woodrow Wilson, was elected in 1913. Mitchel had strong support from progressives. He reorganized city offices, fought against crime, and made taxes more efficient. However, his support for the Allies in World War I upset Germans, and his plans for job training worried working-class people. He lost in 1917 to John Francis Hylan. Hylan was re-elected in 1921 but was later removed by Al Smith and Tammany in 1925.

Tammany knew it needed reformers on its team, but it was hard for them to work together. They needed McClellan to run again in 1905 to beat the strong challenge from publisher William Randolph Hearst. But in 1906, Tammany made a deal and supported Hearst for governor, so McClellan broke away from the machine. Gaynor turned out to be more independent than expected and was not chosen to run again.

Transportation in the City

When the boroughs joined together, it led to more physical connections between them. The New York City Subway opened its first line in 1904. At first, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) systems were separate. A third system, the Independent Subway System (IND), was added in 1925. These subways quickly helped the population spread out and encouraged new development.

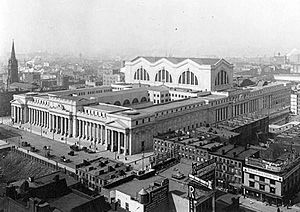

The Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903 and the Manhattan Bridge in 1909. These bridges further connected Manhattan to Brooklyn, which was quickly growing as a place where people lived and traveled to work. The famous Grand Central Terminal opened on February 1, 1913. It was the world's largest train station at the time, replacing an older one. Pennsylvania Station, another large and grand train station, opened in 1910. It was sadly torn down in 1963.

Immigrant Life in New York

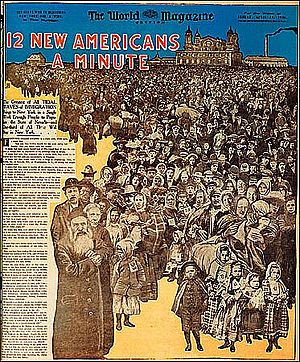

Many people from Europe moved to New York in the early 1900s. This rapid increase stopped in 1914 because of World War I and new laws that limited immigration. The new arrivals were mostly Italian and Polish Catholics, and Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe. Smaller groups continued to arrive from Ireland, Britain, and Germany. The German neighborhood, now called the East Village, saw its residents move to richer areas. More poor immigrants then moved into the Lower East Side.

Jewish Communities

In 1850, about a third of the 50,000 Jewish people in America lived in New York. They spoke German, were part of Reform synagogues, and were important in the city's banking, finance, and clothing industries. A different group of 1.4 million poor Yiddish-speaking Jews came from Russia and Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1914. They were escaping violence and unfair treatment. Over a million of them lived in New York. By 1910, they made up a quarter of the city's population. Many started small shops. Most worked in the city's many small clothing factories, often operating sewing machines.

Conflicts between different ethnic groups were common. Local gangs controlled their neighborhoods and fought with boys who crossed into their areas. Each ethnic group had youth gangs, and Irish gangs were known for being very aggressive. One serious event happened in 1902 during the funeral procession for Jacob Joseph, a chief rabbi. As thousands of Jewish people marched past the Hoe factory, workers or boys threw things from the factory windows. The Jewish marchers fought back and surrounded the factory, breaking its windows. The police, mostly Irish, broke up the fight and arrested some people from both sides. Some Jewish stories blamed the Irish factory workers and police for being unfair. However, later research showed that the factory workers were mostly German, not Irish, and the police were just following normal procedures to stop a riot. Overall, the police generally kept a close watch on violence between groups.

Education in New York

Reformers during the Progressive Era strongly supported free public schooling up through high school. They believed that education was important for personal growth and for gaining skills needed in a modern society. Public school enrollment grew from 553,000 in 1900 to 1.1 million in 1930. The school system included elementary, junior high, and different types of high schools. It also had special schools for music, arts, science, and other trades, as well as programs for children with disabilities and large evening classes for adults. Free public education was especially appealing to poor Jewish immigrants, who valued learning highly.

Other ethnic groups, like Italians, often valued owning a home more. This meant that boys and girls often started working around age 14 to earn money. In Italian communities, girls often left school early to work at home or in factories. This changed in the 1930s, as more Italian girls stayed in school, though still at a lower rate than Jewish girls. Some historians believe this was because American culture was changing their views. Others say it was due to new job opportunities for all young women in New York.

Catholic priests strongly encouraged Catholic schools, especially for elementary students. The Catholic high school system also grew quickly, mainly for German and Irish youth whose families had lived in the city for many years. The Catholic school system grew from 79,000 students in 1900 to 286,000 in 1930. Private schools also did well, along with training schools for adults, like dance or music schools. Many adults also took courses through the mail.

Jewish boys and young men did very well in New York's public schools. However, there were challenges for Jewish girls attending high school. Some Jewish men still had doubts about educating girls, and poor families needed the money girls could earn from full-time jobs. Girls who came to America when they were young learned English quickly. But the older they were when they arrived, the harder the language seemed. Many young Jewish women still tried, which helped them get office and white-collar jobs. Most probably saw their dreams come true through their children rather than themselves.

Higher Education

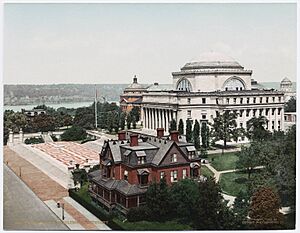

Columbia University became known worldwide as a major research center for many subjects, including arts, sciences, humanities, and medicine. New York University in 1890 was mainly for undergraduate students and had a strong Protestant background. However, it started adding graduate programs, law and medical schools, and business and education schools. It became one of the largest universities in the country, with 9,300 students in 1917 and 40,000 by 1931.

Fordham University led among Catholic colleges, adding medical, law, and business schools. Its football team was nationally famous. Fordham became coeducational (allowing both men and women) in 1964. There were also many smaller specialized schools like Wagner College (Lutheran), Yeshiva University (Jewish), St. John's University (Catholic), Pratt Institute, Juilliard School of Music, Parsons School of Design, Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, and The New School for Social Research. Many medical and law schools also existed.

The city's wealthy Protestant families sent their sons to special preparatory schools in New England and then to Ivy League colleges. Their daughters went to Seven Sisters colleges or finishing schools. After 1900, Columbia was seen as very academic and less appealing to upper-class young men. Jewish student enrollment reached 40% at Columbia College in 1914. A system was then put in place to reduce this to 20%. The public universities, City College and Hunter College, were about 80% Jewish.

Newspapers and Journalism

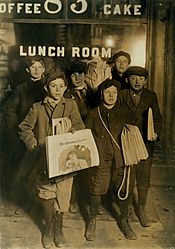

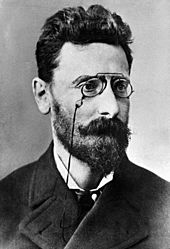

Around 1900, New York City had 15 to 20 daily newspapers and many weekly ones. Most newspapers were sold at newsstands or by newsboys, rather than through subscriptions. The Wall Street Journal gave detailed news about business. The New York Times had almost disappeared by the 1890s. But after Adolph Ochs bought it in 1896, it became popular with a wealthier audience by providing fair and detailed news. There were also many newspapers for different ethnic groups. These ethnic papers helped immigrants stay connected to their home countries. More importantly, they taught them how to become Americans and understand American culture.

Starting in 1895, William Randolph Hearst, a wealthy heir from San Francisco, competed with Joseph Pulitzer from St. Louis for newspaper sales. Both Hearst's Journal and Pulitzer's World supported the Democrats. They both tried to sell more papers by using yellow journalism, which meant sensational stories, sports news, scandals, and features like comic strips, puzzles, recipes, and advice columns. By 1898, both papers sold over a million copies a day. Hearst became a leader of the Democratic Party's left wing. He almost became mayor in 1905 and governor in 1906. He had big disagreements with Al Smith over control of the Democratic Party, losing to Smith in 1925. He then moved his main base to California. After strongly supporting Franklin Roosevelt for president in 1932, he disagreed with Roosevelt and became a critic of the New Deal. He used his national magazines and New York Journal to oppose Roosevelt's plans.

City Disasters

On June 15, 1904, over 1,000 people, mostly German immigrants, died when the steamship General Slocum caught fire in the East River. This was a huge loss for the German-American community.

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Greenwich Village killed 145 young women, mostly Italian and Jewish garment workers. This tragedy led to big improvements in the city's fire department, building safety rules, and workplace laws. The disaster also helped the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union grow, as part of a larger union movement.

On the night of April 14–15, 1912, the ocean liner RMS Titanic sank in the North Atlantic while on its way to New York. About 1,500 of the 2,200 people on board died. On April 18, the rescue ship RMS Carpathia arrived in New York and was met by about 40,000 people. Groups like the Women's Relief Committee and the Travelers Aid Society of New York quickly provided help, including clothes and transportation to shelters. Two memorials for the Titanic are in Manhattan. On April 13, 1913, the 60-foot Titanic Memorial Lighthouse was built on the roof of the Seamen's Church Institute of New York and New Jersey. Straus Park, on the Upper West Side, honors Isidor Straus and his wife Ida Straus, who both died in the disaster.

The Malbone Street Wreck, the worst accident in the history of any rapid transit system in the United States, happened on November 1, 1918. Many subway workers went on strike, so the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) put an office worker in charge of a train. This worker had almost no training and was recovering from the 1918 flu pandemic, which had just killed his daughter. During rush hour, he made several mistakes, lost control, and crashed at a sharp curve near Prospect Park station. The Malbone Street Wreck killed 93 of the 650 passengers and seriously injured over a hundred more. This event became a major issue in the upcoming state election, leading to Al Smith being elected governor.

On September 16, 1920, a terrorist attack, known as the Wall Street bombing, happened outside the headquarters of the House of Morgan. Dozens of people were killed and hundreds injured. Officials blamed anarchists and communists, which fueled ongoing investigations, but the people responsible were never caught.

Gambling in the Early 1900s

Around 1900, gambling was against the law but very common in New York City. Popular games included cards, dice, and numbers games, as well as betting on sports, especially horse racing. For the wealthy, gambling happened secretly in expensive private clubs. The most famous was run by Richard Albert Canfield. Another top club, called the "Bronze Door," was run by a group of gamblers connected to the Democratic political machine. These fancy places were illegal and paid off police and politicians when needed. Working-class people gambled in hundreds of neighborhood parlors, playing card games or betting small amounts on daily numbers. Betting on horse racing was only allowed at the tracks themselves, where rules were strict. Belmont Park was the most famous race track. Middle-class people could go to race tracks, but many in the middle class were strongly against all forms of gambling. The reform movement against gambling was strongest in the 1890s. It was led by people like Reverend Charles H. Parkhurst and reform mayor William L. Strong, whose police commissioner was Theodore Roosevelt. Reformers passed laws against gambling, which were enforced in smaller towns but not in New York's larger cities, where political machines controlled the police and courts.

New York City: 1920s to 1945

Politics and Leadership

The Democrats, led by Al Smith and Robert F. Wagner, supported reforms in the 1910s and 1920s, especially to help working-class people. Smith became governor in the 1920s but lost the presidential election in 1928, even though he did very well in Catholic areas. Wagner served in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1949. He was a leader of the New Deal Coalition and strongly supported labor unions.

The 1924 presidential election, where most New Yorkers voted for Calvin Coolidge, was the last time a Republican presidential candidate won New York City.

After 1928, City Hall faced scandals. The flashy Mayor Jimmy Walker resigned and left for Europe after investigations showed he had taken bribes. This, along with the difficulties of the Great Depression, gave reformers a chance. They won in 1933 with a combined ticket led by Fiorello La Guardia. He was a liberal Republican Congressman with strong Italian and Jewish connections, and he appealed to people from different political parties. La Guardia was the main political figure as mayor from 1934 to 1945. He supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. In return, Roosevelt gave the city a lot of money and stopped supporting La Guardia's political enemies. La Guardia brought new life to New York and made people trust City Hall again. With help from Robert Moses, he oversaw the building of affordable public housing, playgrounds, parks, and airports. He reorganized the police, defeated the powerful Tammany Hall machine, and brought back a system where jobs were given based on skill, not political favors. La Guardia was a strong leader who sometimes seemed bossy, but his reforms were carefully designed to meet the needs of the city's diverse population. He defeated a corrupt Democratic machine, led the city during the Depression and World War II, made New York a model for New Deal programs, and supported immigrants and ethnic minorities. He succeeded with the help of a supportive president who also disliked Tammany Hall. He is remembered as a tough reform mayor who helped clean up corruption, brought in talented experts, and made the city responsible for its citizens. His administration included new groups in the political system, gave New York its modern buildings and roads, and raised hopes for what a city could achieve.

Ethnic Groups Come of Age

Immigrant families continued to settle down, and more started moving to neighborhoods outside Manhattan. In a sign of the city's growth, the 1920 census showed Brooklyn for the first time had more people than Manhattan. But the big period of European immigration, which had just passed its peak, was suddenly stopped by the Immigration Act of 1924. This law greatly limited new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Harlem Renaissance

After 1890, Black people began moving into the neighborhood of Harlem in Manhattan, which used to be mostly Jewish. Many more arrived during World War I as the Great Migration brought Black people north to fill jobs when immigration was paused. Harlem became the political center for Black America, with Marcus Garvey as a controversial leader in the early 1920s. Civil rights activism continued in the 1930s and 1940s, often led by Baptist minister Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who was elected to Congress in 1942. Unemployment was a big problem during the Depression, but New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration provided many jobs equally. Much of the organized protest was about demanding jobs and stores in Harlem that were owned and run by white people.

The Harlem Renaissance, from 1920 to 1940, brought worldwide attention to African American literature. For many years, especially in the 1920s, Harlem was a vibrant place for social thought and culture among many Black artists, musicians, writers, poets, and playwrights. Famous writers included Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Claude McKay, and Zora Neale Hurston.

The Jazz Age in New York

The Jazz Age was a time of famous people and exciting times. Some notable figures in New York City included jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald, dancer Martha Graham, publisher Henry Luce of Time magazine, writer Dorothy Parker, and sports heroes like Babe Ruth and Bill Tilden.

Fun-loving Tammany Mayor Jimmy Walker was in charge during a time of prosperity for the city. Many secret bars, called speakeasies, opened during Prohibition.

Tin Pan Alley, a center for music publishers, moved closer to Broadway. The first modern musical, Jerome Kern's Show Boat, opened in 1927, as the theater district moved north of 42nd Street.

During this period, New York City became known for its bold and impressive buildings, especially the skyscrapers that changed the skyline. The race to build the tallest building ended with two Art Deco icons: the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building. These two skyscrapers were completed when their great heights seemed a bit too hopeful. The construction of the Rockefeller Center also happened then, becoming one of the largest private building projects ever at that time. The city also grew outwards, with homes replacing most of the farms in eastern Brooklyn, eastern Bronx, and much of Queens.

The Great Depression's Impact

The Great Depression, which affected the whole world, began with the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The recently finished Empire State Building was known as the "Empty State Building" for many years because it couldn't find enough renters in the bad economy. When New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt became president, shacks called "Hoovervilles" (named after the previous president) appeared in city parks. The city became a showcase for New Deal spending, especially through the Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration. There were huge building projects, including highways, bridges, public housing, new schools, and expanding the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Parkway planner Robert Moses was in charge of building many bridges, parks, public housing, and parkways, mostly with federal money. Moses strongly supported building things for cars. His many construction projects are still debated today. He was against the huge subway expansions planned in 1929 and 1939. However, the last big expansion of the subway system, along with the city taking over the private subway companies, made the subway system mostly what it is today.

New York During World War II

New York, already a great American city with many immigrants, became a culturally international city. This happened as smart people, musicians, and artists from Europe came as refugees starting in the late 1930s. The 1939 New York World's Fair, celebrating 150 years since George Washington became president in Federal Hall, was a highlight of hope for technology. It was meant to mark the end of the Depression. But after World War II began, the fair's theme changed from "Building the World of Tomorrow" to "For Peace and Freedom." The war in Europe made the event less joyful.

The war turned New York into a major center for the United States home front during World War II. Over 900,000 New Yorkers served in the war. About 63 million tons of supplies and more than 3 million soldiers shipped out from New York Harbor. During the busiest times of the war, a ship left every 15 minutes. Efforts were made to protect New York from attack. Famous places like Times Square and Broadway had their lights dimmed to protect the city from air raids. Posters were put up everywhere to tell people how to react to an air raid or naval attack. Despite these efforts, enemy forces did enter the city during the war. On the evening of January 14, 1942, a German submarine, U-123, entered New York’s Lower Bay. Its crew saw the New York skyline. The U-Boat Captain, Reinhard Hardegen, later wrote about seeing the skyline:

"I cannot describe the feeling with words, but it was unbelievably beautiful and great...I would have given away a kingdom for this moment if I had one. We were the first to be here, and for the first time in this war a German soldier looked upon the coast of the U.S.A."

While U-Boats threatened from the outside, parts of the Nazi Duquesne Spy Ring and Operation Pastorius operated inside the city. New York City's economy got a boost from the war, but not as much as cities with heavy industries like Pittsburgh or Detroit. The clothing industry made uniforms, and machine shops focused on war materials. The Brooklyn Navy Yard again increased its production of warships. The large printing industry was barely affected. The port facilities again played their role in shipping supplies and soldiers to Europe. The Port of New York handled 25% of the nation's exports. By the end of the war, the Navy Yard was the world's largest shipyard with 75,000 workers. When peace came in 1945, New York was clearly the most important city in the world, as it was the only major world city not damaged by the war.

Economy of New York City

Finance and Business

Lower Manhattan in 1931. The American International Building, which would become lower Manhattan's tallest building in 1932, is only partially completed.

|

New York became the financial center of the United States before the Civil War, focusing on railroad investments. By 1900, it became even more powerful and started to rival London as a world financial center. There were thousands of successful bankers and financiers. A key figure was J.P. Morgan, whose company, the House of Morgan, set up national funding for the steel, farming tools, shipping, and other industries. It also helped fund much of Britain's and France's war efforts in World War I. John D. Rockefeller, from Standard Oil, expanded from oil into other industries and banking. Andrew Carnegie was a leader in steel until he sold his company to Morgan in 1901. After 1900, Rockefeller and Carnegie mostly focused on giving money to good causes, as did Morgan to some extent. When the Federal Reserve System was created in 1913, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York became very important under its strong president Benjamin Strong Jr.. By 1917, New York was funding the war efforts of Britain, France, and other Allies. By the 1920s, New York had become a bigger world banking center than London. The New York Stock Exchange was the national hub for making money and investing until its shares suddenly crashed in late 1929, starting the worldwide Great Depression.

The Garment Industry

The garment industry involved making ready-to-wear clothes for men and women, and selling these products to stores across the country. New York City was the main center for this industry in the nation. It started in the 1800s with Jewish tailors, cutters, and sellers. By 1900, Jewish people largely owned and ran the industry, and most workers were Jewish, though other new immigrants were also hired. The Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe strongly supported labor unions, which were linked to their socialist ideas from Europe.

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) formed in 1900 and was a major part of the American Federation of Labor. It grew quickly in its first 20 years. It helped stop sewing work in crowded apartments, set up a six-day, 54-hour work week, created union contracts that favored ILGWU members for jobs, and set up ways to settle disagreements. The union was much larger and stronger than the hundreds of small shops it dealt with. However, in the 1920s, the ILGWU was torn apart by fights between its leaders and Communists. By 1928, the original leaders won. The Communists only controlled the Furriers union, which they ran with violence. ILGWU membership dropped to 40,000 (most of whom were women). The early years of the Great Depression further weakened the union. Under David Dubinsky's leadership, the ILGWU strongly supported Roosevelt's New Deal. Its membership grew quickly in the late 1930s and during World War II.

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America was a more radical group that broke away in 1914. It focused on ready-made clothes for men. It also provided banks, recreation, medical care, and even restaurants and housing for its members. It removed its Communist members in the 1920s. Led by Sidney Hillman, it played a key role in forming the strong Congress of Industrial Organizations in the mid-1930s, giving Hillman a powerful voice in the New Deal Coalition. After 1970, both unions lost members and merged in 1995.

With the Democratic Party in the city mostly controlled by conservative Irish leaders, Dubinsky, Hillman, and their unions formed a new political party in 1936, the American Labor Party. It ran candidates only in New York State, where it strongly supported Roosevelt's three re-elections. When Communists joined the Party in 1944, the ILGWU left and formed the Liberal Party of New York. The Liberal party was led for many years by Alex Rose, who was the leader of the hatters' union, a small garment industry union.

On the Waterfront

The Port of New York and New Jersey was by far the largest American port, serving both passenger and cargo ships. The port was the main place where U.S. troops left for Europe during World War I. The crowded conditions at the port made experts realize the need for a port authority to manage the complex system of bridges, highways, subways, and port facilities in the New York-New Jersey area. The Port of New York Authority was created in 1921, overseen by the governors of New York and New Jersey. By selling its own bonds, it was financially independent of either state. The bonds were paid off from tolls and fees, not from taxes. It became one of the main agencies in the New York metropolitan area for handling large projects, especially under the leadership of Austin Tobin.

Passenger ships were very popular before transatlantic airplanes became common in the 1960s. One type of business served wealthy tourists traveling both ways, with American and British lines competing. Passenger steamships also carried passengers traveling in steerage (a cheaper, crowded part of the ship) at low prices. Most of these were immigrants coming to the United States, though some were immigrants returning to Europe. Two German companies controlled the immigrant traffic to New York from Central and Eastern Europe: the Hamburg-America line and the North German Lloyd. They built large networks of ticket agencies in Europe, offering cheap one-way trips. Immigrants going to other cities usually had tickets paid for by relatives who were already settled in America. Most new arrivals already had some idea of what to expect from family letters and widely available pamphlets. The vast majority of travelers from Europe came through New York City, and immigrants completed their paperwork at Ellis Island. A small percentage were turned away because of obvious diseases. The steamship companies had to pay for their return fare, so they checked for sick passengers in Europe beforehand.

World War I and New York

New York City played a big role in promoting and funding World War I. It also produced uniforms and warships. There was a fear of German sabotage, especially after the Black Tom explosion in 1916.

The Bronx's Story

The history of the Bronx after 1898 has several clear periods. The first was a boom time from 1898 to 1929. The population grew six times, from 200,000 in 1900 to 1.3 million in 1930. The Great Depression brought a lot of unemployment, especially for working-class people, and slowed down growth. The middle to late 20th century were tough times, as the Bronx changed from a mostly middle-income area to a mostly lower-income area with high rates of crime and poverty from the 1950s through the 1970s. An economic comeback began in the late 1980s and continued through the 1990s.

Politics in the borough from 1922 to 1953 were tightly controlled by the Democratic organization, led by Edward J. Flynn. He was often called "the boss." He ran the political machine like a business, carefully choosing his top assistants and providing services to voters who then supported him. Unlike the leaders of Tammany, he worked very well with Franklin Roosevelt, both as governor and as president.

Images for kids

-

Mulberry Street, on the Lower East Side, around 1900

| Preceded by History of New York City (1855–1897) |

History of New York City (1898–1945) |

Succeeded by History of New York City (1946–1977) |

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva York (1898-1945) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva York (1898-1945) para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |