History of the New York City Subway facts for kids

The New York City Subway is a huge train system that runs underground and above ground in New York City. It serves four of the five main areas, called boroughs: the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) runs the subway, and it's part of the larger Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). In 2016, about 5.66 million people rode the subway every day. This makes it the busiest train system in the United States and one of the busiest in the world!

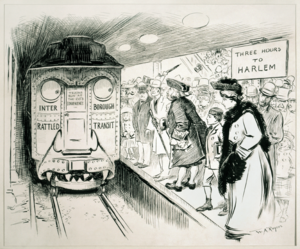

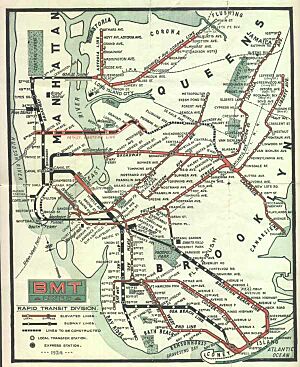

The first underground subway line opened on October 27, 1904. But New York City already had elevated (above-ground) train lines for almost 35 years before that. By the time the subway started, two big private companies ran most of the train lines: the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later called BMT) and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). After 1913, the city started building new lines and then leased them to these companies. In 1932, the city opened its own train system, the Independent Subway System (IND). It was meant to compete with the private companies and replace some of the older elevated lines.

In 1940, New York City took over all the private train systems. Some elevated lines closed right away, and others closed soon after. The IND and BMT lines were later connected and now work together as the "B Division." But the IRT lines are still separate (called the "A Division") because their tunnels and trains are too small for the B Division cars.

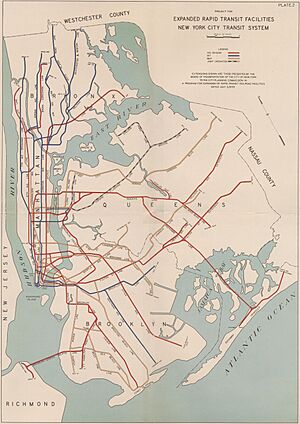

The NYCTA was created in 1953 to run the subway, buses, and streetcars. In 1968, the state-level MTA took control of the NYCTA. The 1970s were tough for New York City, and the subway faced many problems. Many elevated lines closed because they were too expensive to keep up. Graffiti, crime, and broken-down trains became common. The subway had to cut services and delay important repairs. But in the 1980s, a big $18 billion plan started to fix up the subway system.

The September 11 attacks in 2001 caused big problems for the subway, especially the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line. This line ran right under the World Trade Center. Parts of the tunnels were crushed, and trains couldn't run south of Chambers Street. By March 2002, most of the closed stations were rebuilt and reopened.

Since the 2000s, the subway has expanded again. The 7 Subway Extension opened in September 2015, and the first part of the Second Avenue Subway opened on January 1, 2017. However, at the same time, not enough money was spent on keeping the older parts of the subway in good shape. This led to a big transit crisis in 2017.

Contents

Early Train Systems

First Attempts Underground

Even before the subway, there was an underground railroad called the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel in 1844. It was built to help trains avoid street traffic. This tunnel closed in 1861, but it reopened for tours in 1982 before closing again in 2010.

The first ideas for a subway came from various elevated train lines in Manhattan and Brooklyn. These were steam-powered trains that ran above the streets. The very first elevated line was built from 1867 to 1870 by Charles Harvey. More elevated lines were built on Second, Third, and Sixth Avenues. None of these old structures are still standing today.

In Brooklyn, elevated railroads were also built by different companies. These lines later became part of the BRT and BMT systems. Many of these elevated lines were taken down, but some were rebuilt and improved. These lines connected to Manhattan using ferries and later the tracks on the Brooklyn Bridge.

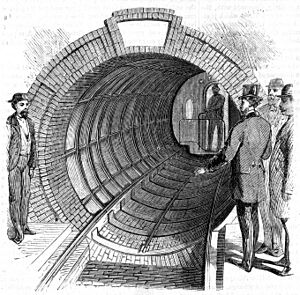

Beach's Pneumatic Subway

The Beach Pneumatic Transit was the first try at building an underground public train system in New York City. In 1869, Alfred Ely Beach started building a subway line under Broadway. He used $350,000 of his own money for the project. It was built very quickly, in just 58 days! The tunnel was 312 feet long and 8 feet wide.

It was more of a curiosity than a real subway. It only had one car that went back and forth on a single block. People would ride it just to see what a subway might be like. Many people liked it at first, but Beach had trouble getting permission to make it bigger. By the time he finally got approval in 1873, people had lost interest and money. The subway closed down.

A stock market crash in 1873 was the final blow. The tunnel entrance was sealed, and the station was used for other things. Today, no part of this original tunnel remains.

Subway Begins and Grows Fast

The First Subways Are Built

IRT System

In 1898, New York City became much bigger, combining Manhattan, Brooklyn, and parts of Queens and the Bronx. The city decided that future train lines should be underground subways. But no private company wanted to pay the huge amount of money needed to build under the streets.

So, the city created the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners in 1894. This group would plan the routes and find a company to build and run the subway. After some legal challenges, a route was chosen that went from City Hall north to Kingsbridge and another branch to Bronx Park.

The city decided to pay for the subway itself by selling special bonds. It then hired the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) to equip and operate the subway. The IRT already ran the elevated lines in Manhattan. They agreed to share profits with the city and keep the fare at a fixed five cents.

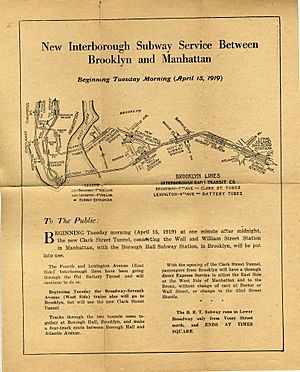

Construction officially began on March 24, 1900. The first subway line opened on October 27, 1904. It ran from City Hall to 145th Street on the West Side. Over the next few years, the line was extended further north. The first underwater subway tunnel, the Joralemon Street Tunnel, opened on January 9, 1908. It connected Manhattan and Brooklyn.

BRT System

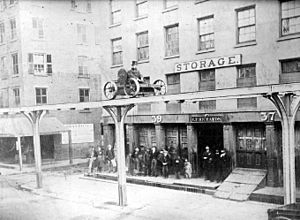

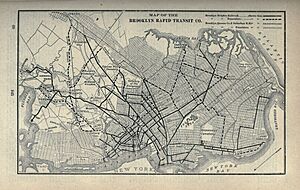

The Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT), later called the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT), also ran train lines in New York City. They started with elevated railways and later added subways.

The BRT was formed in 1896. It quickly took over many smaller train companies in Brooklyn. By 1900, the BRT controlled almost all the train and streetcar operations in its area. Most of these lines were originally steam-powered but were changed to run on electricity between 1893 and 1900.

The BRT went bankrupt in 1918, partly because of a big train crash. It was then reorganized into the BMT in 1923.

Big Expansion Plans

Original IRT and BRT Agreements

After the city was allowed to borrow more money, there were many plans for new subway lines. The "Triborough plan" included three new lines:

- An IRT line from South Ferry in Manhattan to the Bronx.

- A BRT line connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan using the Manhattan Bridge and Williamsburg Bridge.

- A BRT subway under Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, leading to Bay Ridge and Coney Island.

The BRT lines were built with wider tunnels and trains than the IRT lines. This was because the BRT wanted to carry more passengers and didn't want to use the IRT's smaller tracks.

Dual Contracts

The city made a big agreement called the "Dual Contracts" on March 19, 1913. This allowed both the BRT and IRT to expand their systems. The city would build new subway and elevated lines, fix up old ones, and then lease them to the private companies to operate. The city and the companies would share the costs.

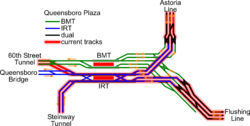

As part of these contracts, the two companies shared lines in Queens, like the Astoria Line and the Flushing Line. These lines started from Queensboro Plaza. The IRT could go directly to Manhattan, but BRT passengers had to switch trains. This was important later when the subway was extended for the 1939 World's Fair.

The Dual Contracts also changed how the original IRT system worked. Instead of a "Z" shape, it became an "H" shape. This meant two main lines (Lexington Avenue and Broadway–Seventh Avenue) connected by the 42nd Street Shuttle. This change doubled the capacity of the IRT system.

The Dual Contracts helped New York City grow. People moved to new homes built along the new subway lines. These homes were affordable, and the subway helped spread out the city's crowded areas.

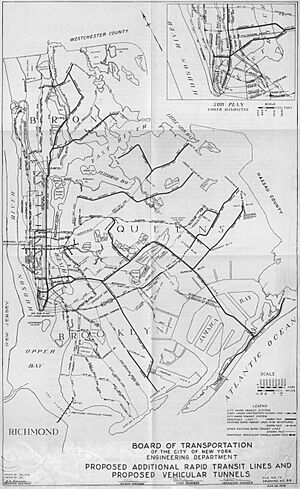

Independent System (IND)

Mayor John F. Hylan wanted the city to run the subway. He thought private companies were making too much money. He tried to make it hard for the BRT and IRT to operate. New York City also needed more subway lines because its population was growing fast.

So, the city decided to build its own subway system, called the Independent City-Owned Subway (ICOS), later known as the Independent Subway System (IND). The city wanted to build, equip, and operate this new system itself, without private companies.

The first IND line, the IND Eighth Avenue Line, opened on September 10, 1932. It ran from 207th Street in Inwood to Hudson Terminal (now World Trade Center). All of the original IND lines were underground, except for a few stations in Brooklyn.

Later, the IND Sixth Avenue Line opened in 1936. The city even bought and closed an old elevated line to make way for it. The IND Queens Boulevard Line also opened in sections, starting in 1933. This line helped take passengers away from other train lines.

In 1937, the IND Crosstown Line opened. By 1940, the Sixth Avenue line was fully open. Plans for a IND Second Avenue Line were also made, but the Great Depression and World War II caused delays. Construction on it was postponed for a long time.

The IND system was very well-built, almost entirely underground, with long platforms and special track designs. However, building it tripled the city's train debt. This led to many big expansion plans being canceled.

Unification and Changes

In June 1940, the New York City Board of Transportation took over the IRT and BMT systems. In 1953, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) took over. This takeover happened as the main period of subway building in New York City ended. The city immediately started closing elevated lines it thought were no longer needed. This included parts of the IRT Ninth Avenue and Second Avenue lines, and several BMT lines in Brooklyn.

Different Train Divisions

Even after the systems joined, they kept their differences. IRT lines (now called "A Division") use numbers for their trains, while BMT/IND lines (now "B Division") use letters. There's also a physical difference: A Division cars are narrower and shorter than B Division cars. This is because the IRT and BRT had a long-standing disagreement, and the BRT intentionally built wider cars.

A Division trains can travel on B Division lines if needed, but they don't carry passengers there. This is because there would be a dangerously wide gap between the smaller A Division cars and the wider B Division station platforms. Most new subway lines built after World War II were for the B Division because its trains can carry more passengers.

After Unification

New York City hoped that the money from the old private lines would help pay for the expensive IND lines and their debts, without raising the five-cent fare. But during World War II, prices went up. The fare had to increase to ten cents in 1947, and then to 15 cents six years later.

Ridership went way up in the late 1940s. On December 23, 1946, a record 8,872,249 people rode the subway in one day!

The NYCTA was created in 1953 to make sure the subway ran efficiently. Many old trains and tracks from the former private lines needed to be fixed. New trains were bought, and station platforms were made longer to fit more cars. Air conditioning was also added to some trains in the 1960s.

Only two new lines opened during this time: the IRT Dyre Avenue Line in 1941 and the IND Rockaway Line in 1956. Both of these were old railroad tracks that were fixed up for subway use, not completely new construction.

Decline and Comeback

The subway system was slowly neglected from the 1940s onwards. Not enough money was spent on maintenance. In the 1970s, the city faced a financial crisis. More elevated lines closed, like the IRT Third Avenue Line in Manhattan (1955) and the Bronx (1973).

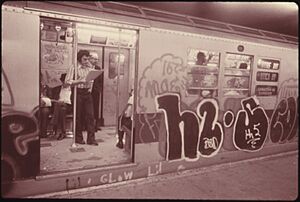

Construction and maintenance were put off. Graffiti and crime became very common. Trains often broke down, were poorly kept, and were late. Ridership dropped by millions each year. By 1980, trains were ten times less reliable than in the 1960s. Many tracks needed speed limits because they were in bad shape.

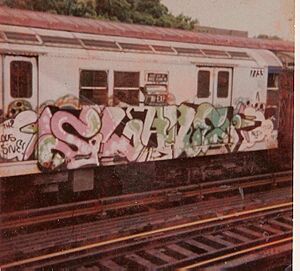

Graffiti Problem

In the 1970s, almost every subway car was covered in graffiti. The city didn't have enough money to clean it or fix the trains. Mayor John Lindsay declared a "war on graffiti" in 1972. Cleaning cars with acid solutions was tried, but it was expensive and sometimes damaged the trains.

As graffiti became linked with crime, people wanted the government to take it more seriously. In the 1980s, more police and security (like razor wire and guard dogs) were used. There were also constant efforts to clean the trains. This helped to reduce the graffiti problem. By May 10, 1989, all subway trains were finally graffiti-free.

Ridership Drops and Service Cuts

By 1975, subway ridership was as low as it had been in 1918. The MTA cut the length of trains during off-peak hours and stopped work on several projects, including the Second Avenue Subway. Ridership kept falling fast. In 1976, the MTA cut 279 train runs to save money.

In 1986, the NYCTA even considered closing 79 stations on 11 routes because of low ridership and high repair costs. Many people, including city council members, criticized these plans.

Infrastructure Problems

The subway's condition became very dangerous in the early 1980s. Structural problems were found in elevated tracks and on the Manhattan Bridge and Williamsburg Bridge. This caused frequent closures and delays. Trains often derailed, and cars caught fire 2,500 times every year. Many trains were out of service due to serious technical problems.

In 1981, officials even suggested closing parts or most of several lines, or even shutting down the subway at night to reduce crime.

Rehabilitation and Improvement

Ridership started to increase again in the late 1970s, partly because the economy was getting better. Many improvements were made, like adding air conditioning and closed-circuit television.

In 1982, the MTA started a big plan to fix the system. Old trains were repaired and replaced. New maps were added to stations. Train derailments became much less common. The tracks were almost completely renewed within ten years. The Williamsburg Bridge and Manhattan Bridge were also repaired.

The stations got fresh paint, new lights, and better signs. The MTA also tried to improve service by giving staff new uniforms and training. Crime in the subway dropped a lot in the 1990s.

Projects During This Time

Starting in the 1970s, there were plans to improve the subway. In 1978, the MTA opened three new transfer stations to make it easier to switch between lines. These included connections at 14th Street, Canal Street, and Atlantic Avenue–Barclays Center.

In 1981, the MTA started installing welded rails in some underground parts of the system to make tracks smoother.

In December 1988, three more transfers opened, making it easier to connect between stations like Lexington Avenue/53rd Street and 51st Street. Three brand-new stations also opened in Queens, as part of the Archer Avenue Lines.

New subway cars were bought between 1983 and 1989. These new trains replaced many of the older cars.

On October 29, 1989, the IND 63rd Street Line opened. It was sometimes called the "tunnel to nowhere" because it ended abruptly at 21st Street–Queensbridge. It was seen as a big waste of money at the time.

Revitalization and Recent History

The 1990s

Subway ridership continued to grow throughout the 1990s. In 1998, a large part of the New York City Subway system was nominated to be added to the National Register of Historic Places. This would help the MTA get more money from the government to fix things up.

September 11, 2001 Attacks

The September 11 attacks caused major problems for subway lines in Lower Manhattan. Tracks and stations under the World Trade Center were shut down quickly. All subway service was stopped for a few hours. After the Twin Towers collapsed, many trains lost power and had to be evacuated.

The IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line was the most damaged. Parts of its tunnel and the Cortlandt Street station were badly hurt and needed to be rebuilt. Service was stopped south of Chambers Street. Other lines also faced disruptions and flooding.

Normal service on most lines was restored by September 15, 2002. However, the Cortlandt Street station needed a complete rebuild, costing $158 million. It finally reopened on September 8, 2018.

Later 2000s

More Ridership

Ridership kept going up as the subway got better. It was cleaner, safer, and trains ran more often and on time. From 1995 to 2005, ridership grew by 36%. In 2008, with higher gas prices and more tourism, ridership reached its highest level since 1965.

By 2013, ridership was at 1.7 billion riders per year, a level not seen since 1949. In 2014, the subway had 6 million daily riders on 29 days, showing how crowded it was becoming.

New Expansions

Several new subway expansions started or opened in the 2000s. The IND 63rd Street Line was connected to the IND Queens Boulevard Line on December 16, 2001. This changed some train routes and added new transfer options.

In 2009, a new South Ferry station opened. The old station could only fit five cars of a train, but the new one could fit all ten cars. This saved passengers time and allowed more trains to run.

Talk about building the Second Avenue Subway started again in the late 1990s. Many New Yorkers were doubtful, as the line had been promised for decades. But in 2007, construction finally began.

In 2007, the 7 Subway Extension also started construction. This line would extend the IRT Flushing Line to 34th Street. It was the first project funded by the city in over 60 years and was meant to help develop the Hell's Kitchen area.

Budget Cuts

The MTA faced a big budget problem in 2009. This led to higher fares and fewer services. Two part-time subway lines, the V and W, were eliminated. Other routes were changed, and trains ran less often during off-peak hours.

2010s and 2020s

Hurricane Sandy Damage

On October 28, 2012, the subway system was completely shut down before Hurricane Sandy hit. The storm caused major damage, especially to the IND Rockaway Line. Many parts of this line were heavily damaged, cutting it off from the rest of the system. The NYCTA had to bring in 20 subway cars by truck to provide temporary service in the Rockaways. The line reopened on May 30, 2013, with new walls to protect against future storms.

Several tunnels under the East River were flooded. The South Ferry station was badly damaged and had to use its old loop station temporarily. Many tunnels were closed for repairs over the next few years.

New Expansions Open

The new South Ferry station, costing $530 million, opened on March 16, 2009. The 7 Subway Extension was supposed to open in 2014 but finally opened on September 13, 2015. The Fulton Center building, a refurbished station in Lower Manhattan, opened in November 2014.

As part of the opening of the Second Avenue Subway, the W train service was brought back on November 7, 2016. The first phase of the Second Avenue Subway officially opened on January 1, 2017.

2017 Transit Crisis

Despite the new expansions, the subway's maintenance slowly got worse. By 2017, only 65% of weekday trains were on time, the lowest rate since the 1970s. In the summer of 2017, the subway system was officially declared in a "state of emergency" because of many train derailments, track fires, and overcrowding.

To fix these problems, the MTA announced a "Genius Transit Challenge" to get ideas for improvements. They also started a $9 billion "New York City Subway Action Plan" to stabilize the system. In November 2017, The New York Times reported that the crisis was caused by bad financial decisions by politicians over many years.

Many improvements were made, including fixing signals, trains, and tracks. The MTA also plans to add elevators and ramps to 66 subway stations and install modern signaling systems. The state of emergency officially ended on June 30, 2021.

Future Plans

There are several new subway lines being considered for the future. These include a line under Utica Avenue in Brooklyn, a line connecting different boroughs, and a line to LaGuardia Airport.

The MTA is also planning Phase 2 of the Second Avenue Subway, which will extend it further north into East Harlem.

Further Upgrades

In the early 2020s, more upgrades were announced. A new fare payment system called OMNY was put in place. The MTA also plans to install platform screen doors at some stations and make 95% of subway stations accessible for wheelchairs by 2055. Even with fewer riders due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the MTA balanced its budget by 2023 and increased service on some lines.

Images for kids

-

Hurricane Sandy caused serious damage to the IND Rockaway Line and isolated one part of the line from the rest of the system, requiring the NYCTA to truck in 20 subway cars to the line to provide some interim service in the Rockaways. This shows one of the cars being loaded onto a flatbed to be carried to the Rockaways.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Metro de Nueva York para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Metro de Nueva York para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |