History of transportation in New York City facts for kids

New York City's transportation system has a long and interesting history! It started with the Dutch in the 1600s, grew a lot during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, and then changed even more with big projects led by people like Robert Moses. Today, New York City, the biggest city in the United States, has a huge transportation network. It includes one of the world's largest subway systems, the first vehicle tunnel with mechanical ventilation, and even an aerial tramway (like a cable car in the sky!).

Contents

How New York City's Transport Began

Long before Europeans arrived, parts of what is now Broadway were important paths for the Lenape people. In the 1700s, the main road to far-off places was the Eastern Post Road. It went through the East Side of Manhattan and out of its northernmost point. Another important road, now Broadway, was called Bloomingdale Road. Other streets like Lafayette Street, Park Row, and St. Nicholas Avenue also follow old Lenape paths. The Dutch called the main Lenape path running through Manhattan the Heere Wegh. The first paved street in New York was built in 1658 on what is now Stone Street, ordered by Peter Stuyvesant.

Lenape paths weren't just in Manhattan. Jamaica Avenue, which connects Brooklyn and Queens today, also follows an old trail through Jamaica Pass.

The early Dutch city, Nieuw Amsterdam, used the surrounding rivers a lot. They built canals, including one on what is now Broad Street, called the Heere Gracht. A city pier was built on what is now Moore Street, on the East River. The first road built out of Nieuw Amsterdam connected it to Nieuw Haarlem (Harlem). This "wagon-road" was built in 1658 by order of Peter Stuyvesant to help Nieuw Haarlem grow and protect Nieuw Amsterdam.

In 1661, the Communipaw ferry started. This began a long history of ferries and later trains and roads crossing the Hudson River.

Transportation in the 1800s

The New York colony improved the old Native American trails. Roads good for wagons included the King's Highway in Kings County and the Boston Post Road.

As the city grew, new streets were planned. The areas near the rivers were developed first, with streets running parallel and perpendicular to the water. By the early 1800s, the city had grown north to about Houston Street. With more world trade, New York was growing fast. So, a special group created a big plan for the rest of Manhattan.

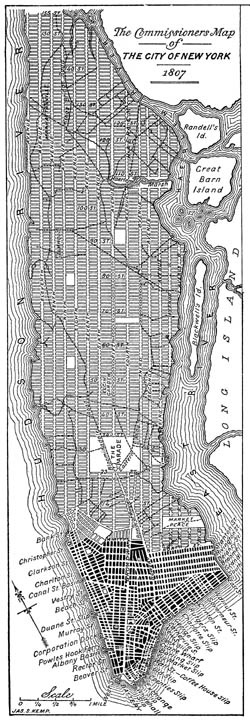

New York decided to use a special plan called the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 to develop Manhattan north of 14th Street with a regular street grid. This plan completely changed the city's look and economy. It called for twelve numbered avenues running north-south and 155 cross streets. The idea was that this regular grid would make it easy to build new properties and help businesses grow.

By the mid-1800s, most streets were still unpaved. But tracks allowed smooth public transport using horse cars, which later became electric trolleys. In 1854, the Jennings streetcar case helped end racial discrimination on public transport.

Water Travel Expands

Water transport grew quickly in the 1800s, partly thanks to Robert Fulton's steamboat inventions. Steamboats offered fast and reliable connections from New York Harbor to other ports along the Hudson River and coast. Later, local steam ferries allowed people to live further from their jobs. The world's first steam ferry service started in 1812 between Paulus Hook and Manhattan, cutting travel time to just 14 minutes.

In 1825, the Erie Canal was finished, connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie. This made New York the most important link between Europe and the American interior. Canals like the Gowanus Canal were built to handle the extra traffic. The Morris Canal and Delaware and Raritan Canal also brought coal and other goods to the city. However, the "Canal Age" soon gave way to the "Railway Age."

New York's ports kept growing fast, becoming America's main entry point for manufactured goods and immigrants, and sending out grains and raw materials. By the mid-1800s, more passengers and products came through the Port of New York than all other U.S. harbors combined, thanks to the new oceanic steamships.

Streetcars found steam power difficult, so they usually went straight from horse power to electricity. In the suburbs, true trolley cars with overhead wires were used. But in Manhattan, overhead wires were not allowed. Heavy Traffic congestion and the high cost of underground power collection slowed down streetcar development there.

New York's waterways, which were so helpful for trade, became obstacles for railroads. Freight cars had to be carried across the harbor by car floats (barges that carry trains). This added to the already busy harbor traffic.

Because the Harlem River was not too wide, three railroads agreed to build a shared Grand Central Terminal. But disagreements among New Jersey railroad companies stopped plans for a big new rail bridge across the Hudson. So, the Pennsylvania Railroad built the New York Tunnel Extension for its new Pennsylvania Station. Passengers from other companies would switch to the Pennsylvania Railroad or continue to cross the Hudson by ferries and the Hudson Tubes.

The Gowanus Canal was too small for the large barges of the late 1800s. So, Newtown Creek was also made into a canal. This helped serve new gas works and later refineries and chemical factories. These changes turned Greenpoint, Bushwick, Maspeth, and other nearby towns into industrial areas, which later became part of the City of Greater New York.

Waterways weren't just for work. People also enjoyed pleasure trips. Mark Twain's Innocents Abroad describes early cruise ship voyages for wealthy people in the 1860s. The 1904 General Slocum disaster reminds us of the many day trips organized for ordinary people. Some trips went to amusement parks, while others just went to a dock with a path to a meadow for dancing and picnics, away from the busy city. Some people visited the Great Falls of the Passaic River by train or even bicycle tours. The Hudson River Day Line was the last company offering regular day trips from West 42nd Street, closing in the 1970s.

The Brooklyn Bridge

Designed by John Roebling, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first connection between Manhattan and Long Island. It was famous for its size, beauty, and business importance. When it was finished in 1883, its main span of 1,596 feet 6 inches was the longest of any bridge in the world. This period helped establish the idea of combining smaller cities and towns into what became the City of Greater New York.

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883. Thousands of people and many ships attended the opening ceremony. President Chester A. Arthur and New York City Mayor Franklin Edson crossed the bridge with celebratory cannon fire. They were greeted by Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low when they reached the Brooklyn side. John Roebling's son, Washington Roebling, who oversaw much of the construction, was unable to attend the ceremony due to illness. He held a celebration at his home. The festivities included a band, gunfire from ships, and fireworks.

On that first day, 1,800 vehicles and 150,300 people crossed the bridge. Emily Warren Roebling, Washington's wife, was the first to cross. The bridge cost $15.5 million (in 1883 money) to build, and about 27 people died during its construction.

Other bridges across the East River were built soon after, including the Williamsburg Bridge (1903), the Queensboro Bridge (1909), and the Manhattan Bridge (1909).

The Rise of Rails

Steam railroads, which started in places without many waterways, soon reached New York. They became important for competition among port cities. New York, with its New York Central Railroad, became the most important city for international trade with the U.S. interior. As the West and East sides of Manhattan became more crowded, local railroads were built above or below ground to avoid street traffic. Intercity railroads moved their stations from Downtown Manhattan to other areas. Soot and sparks from steam locomotives became a problem, so the railroads switched to electric power. A network of roads and elevated railroads grew, connecting and developing Long Island, especially its western parts.

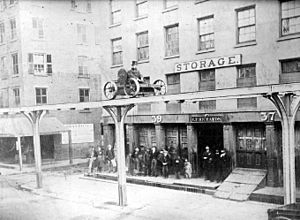

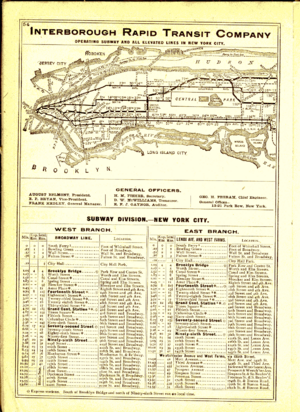

New York wasn't the first U.S. city to have rapid transit, but it quickly caught up. Elevated trains started modestly on 9th Avenue in 1867-70. By the 1880s, they covered much of Manhattan and western Brooklyn. These early elevated lines were built on Second, Third, and Sixth Avenues. None of these original structures remain today. They later shared tracks with subway trains as part of the IRT system.

In Brooklyn, elevated railroads were also built on Lexington, Myrtle, Third, and Fifth Avenues, and Fulton Street and Broadway. These also later shared tracks with subway trains and even ran into the subway, as part of the BRT and BMT systems. Most of these structures have been taken down, but some rebuilt parts still exist. These lines connected to Manhattan by ferries and later by tracks on the Brooklyn Bridge.

In 1898, New York, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and parts of Queens and Westchester were combined into the City of Greater New York. During this time, the expanded city decided that future rapid transit should be underground subways. However, no private company wanted to pay the huge cost of building tunnels under the streets.

The City decided to use special bonds to build the subways itself. It then hired the IRT (which already ran the elevated lines in Manhattan) to run the subways. They would share the profits, and the fare was set at a fixed five cents.

Transportation in the 1900s

The first bike lane in the United States was created by the City of Brooklyn in 1894. Cycling in New York City grew quickly in the early 1900s. But soon, new technology brought even faster vehicles.

Air Travel Takes Off

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia helped build an airport in Brooklyn and two larger ones in Queens. One was named after him, LaGuardia Airport, and the other after President John F. Kennedy. The Queens airports grew and became very successful. Floyd Bennett Field eventually stopped regular passenger service.

The Age of Cars

John D. Hertz started the Yellow Cab Company in 1915, which operated taxis in many cities, including New York. Hertz chose yellow for his cabs because he read that it was the most visible color from a distance.

In the late 1910s, Mayor John Francis Hylan allowed a system of "emergency bus lines." These were later ruled illegal by courts, and those that continued to operate got special permits from the city.

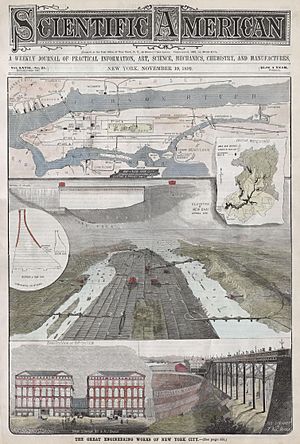

More and more private automobiles greatly changed transportation projects built after 1930. In 1927, the Holland Tunnel, built under the Hudson River, was the world's first vehicle tunnel with mechanical ventilation. The Holland and Lincoln tunnels were built instead of bridges to allow large ships to pass freely in the port, which was still very important for New York City's industry. Other 20th-century bridges and tunnels crossed the East River, and the George Washington Bridge was built higher up the Hudson.

In 1967, New York City ordered all "medallion taxis" (licensed cabs) to be painted yellow.

Water Transport Continues

In the early 1900s, the Department of Dock and Ferries built a series of piers south of 23rd Street to handle the growing traffic of large passenger steamships. These piers were later called Chelsea Piers.

The Port of New York Authority took charge of Hudson River crossings, freight piers, and built an Inland Freight Terminal in Lower Manhattan. The Port Authority helped the ocean cargo industry switch from loading individual items to using containerization (large metal boxes), mostly at ports on Newark Bay. They also built a Downtown truck terminal and a Midtown bus terminal. They took over the struggling Hudson Tubes that carried commuters from New Jersey to Manhattan. Plans for a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel to replace train-carrying barges didn't happen. Instead, most land freight switched to trucks. The Port Authority also took over and expanded the major airports owned by New York City and Newark, New Jersey.

During World War II, the New York Port of Embarkation handled about 44% of all military personnel and 34% of all cargo shipped out to war.

Subway System Grows

Rapid transit grew even faster under the Dual Contracts of 1913. Most of today's subway system was built or improved under these contracts. They created new lines and added tracks and connections to existing ones. The Astoria Line and Flushing Line were built then. Under these contracts, the city would build new subway and elevated lines, improve old ones, and lease them to private companies to operate. The cost was shared almost equally by the City and the companies.

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia oversaw the building of the Independent Subway System, which his predecessors had started. The City decided it would build, equip, and operate a new system itself, without private companies sharing the profits. This led to the building of the Independent City-Owned Subway (ICOS), also called the Independent Subway System (ISS) or simply The Eighth Avenue Subway. After the City bought the BMT and IRT in 1940, the Independent lines were called the IND. The original IND system was mostly underground, except for the Smith–Ninth Streets and Fourth Avenue stations on the Culver Viaduct over the Gowanus Canal in Gowanus, Brooklyn.

Building new subways almost stopped between the 1950s and the 2000s. Planned expansions were delayed and then made smaller.

The original IND system was completed after World War II. But then, the system entered a period where maintenance was put off, and the infrastructure got worse. In 1951, a half-billion dollar bond was approved to build the Second Avenue Subway. However, this money was used for other things and to build short connecting lines. These included a ramp extending the IND Culver Line to Coney Island (1954), the 60th Street Tunnel Connection (1955), and the Chrystie Street Connection (1967).

Soon after, the city faced a money crisis. Construction and even maintenance of existing lines were delayed. Graffiti and crime were very high. Trains often broke down, were poorly maintained, and were late. Millions of riders stopped using the subway each year. Elevated lines continued to close. These included the entire IRT Third Avenue Line in Manhattan (1955) and the Bronx (1973), as well as parts of the BMT Lexington Avenue Line (1950), BMT Fulton Street Line (1956), BMT Myrtle Avenue Line (1969), and the BMT Culver Shuttle (1975), all in Brooklyn. Only a few parts of the big 1968 "Program for Action" were ever opened: the Archer Avenue Lines and 63rd Street Lines in the late 1980s.

Robert Moses's Influence

Mayor La Guardia appointed a powerful young man named Robert Moses as Commissioner of Parks. In the West Side Improvement project, Moses separated the freight train service of the West Side Line from street life, which helped both the trains and the parks. Later, Moses extended parkways (special roads for cars) even further. After 1950, the federal government focused on freeways, and Moses worked hard on building those.

Robert Moses was a key figure in changing New York's landscape, adapting it for cars after 1930. He designed many limited-access parkways in four boroughs, which were meant to connect New York City to its more rural suburbs. Moses also created many public institutions and large parks. With only one exception (the East River Drive), Moses planned every major highway, parkway, expressway, tunnel, or road in and around New York City. He designed all 416 miles of parkways. Between 1931 and 1968, seven bridges were built between Manhattan and the surrounding land, including the Triborough Bridge and the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island, was the longest suspension bridge in the world when it was finished in 1964. Moses was also important in designing several tunnels, including the Queens–Midtown Tunnel (the largest non-federal project in 1940) and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1950.

Late 1900s Changes

In the 1960s, the State took over two struggling suburban commuter railroads and combined them, along with the subways and various agencies Moses had created, into what was later named the MTA. In the 1970s, the modern New York Passenger Ship Terminal replaced the Chelsea Piers, which were no longer useful for the new, larger passenger ships.

Transportation in the 2000s

Since the early 2000s, many ideas for improving New York City's transit system have been discussed, planned, or started. As part of PlaNYC 2030, a long-term plan for the city's environmental sustainability, Mayor Michael Bloomberg suggested ways to increase public transit use and improve overall transportation.

The city's two major airports are being improved. LaGuardia Airport started a $4 billion renovation in 2016, set to finish by 2021. Terminals are being rebuilt and connected. An AirTrain LGA (a people mover) will also be built. John F. Kennedy International Airport is also undergoing a $10.3 billion redevelopment, one of the largest airport projects in the world. Terminals 1, 4, 5, and 8 have been rebuilt recently. In 2007, the Port Authority approved plans to buy a lease for Stewart International Airport in Newburgh, New York, to add more airport capacity.

The subway has also received several major expansions. The Fulton Center, a $1.4 billion project near the World Trade Center, improved access and connections between PATH and subway lines. It started construction in 2005 and opened in November 2014. The nearby World Trade Center Transportation Hub for the PATH train opened on March 4, 2016, costing $3.74 billion. The 7 Subway Extension extended the 7 <7> trains line from Times Square to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center/Hudson Yards area at the 34th Street station. Tunnel construction began in 2008, and service started on September 13, 2015. Finally, the Second Avenue Subway, a new north-south line, was proposed to run from 125th Street in Harlem to Hanover Square in lower Manhattan. The first part, from Lexington Avenue–63rd Street to 96th Street, opened on January 1, 2017.

There have also been efforts to rebuild and improve commuter rail. The Moynihan Station project will expand Penn Station into the James Farley Post Office building across the street. The first part opened in June 2017, and the second phase began in August 2017. The East Side Access project will send some Long Island Rail Road trains to Grand Central Terminal instead of Penn Station, and is planned to be finished by 2023. The Gateway Project, set for completion by 2026, will add a second pair of railroad tracks under the Hudson River, connecting an expanded Penn Station to NJ Transit and Amtrak lines. This project replaces a similar one called Access to the Region's Core, which was canceled in 2010. One idea that didn't happen was the Lower Manhattan–Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project, which would have created a new LIRR line from John F. Kennedy International Airport to Lower Manhattan.

Although New York City does not have light rail (like a modern streetcar), a few ideas exist. The most likely planned light rail route is the Brooklyn–Queens Connector, a streetcar route proposed for the western shore of Long Island. The city officially supported it in 2016, and it is planned for completion after 2024. There are also plans to turn 42nd Street into a light rail area, closed to all vehicles except emergency ones. This idea was planned in the early 1990s and approved in 1994, but it stalled due to lack of money. It is also opposed by the city government because it runs parallel to the Flushing/42nd Street subway line (7 <7> trains). Staten Island light rail proposals for the North and West Shores have political support but are not funded. The Brooklyn Historic Railway Association is also planning light rail in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

Mayor Bloomberg's other ideas included adding bus rapid transit, reopening closed LIRR and Metro-North stations, new ferry routes, better access for cyclists and pedestrians, and a congestion pricing zone for Manhattan south of 86th Street. The bus rapid transit system, Select Bus Service, started in 2008. The city's cycling network grew, and Citi Bike, a citywide bike share, opened in 2013. NYC Ferry, a citywide ferry system, started its first routes in May 2017. Penn Station Access, which would reopen several Metro-North stations, was considered for the MTA's 2015–2019 Capital Program but can't happen until East Side Access is finished.

Although Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan was initially rejected in 2008, Governor Andrew Cuomo reconsidered the idea in 2017. Cuomo appointed a group that released recommendations for a congestion pricing plan in January 2018.

The Regional Plan Association released its fourth Regional Plan in November 2017. One part of this plan included four lists of ideas to improve the city's transit system. The first list focused on improving regional transport by building a new bus station, digging more railroad tunnels under the East and Hudson Rivers, renovating Penn Station, and combining the Metro-North, LIRR, and NJ Transit railroads. The second list, about the subway, included building eight new subway lines, renovating stations with elevators and platform screen doors, and automating the subway. The third list covered vehicle transport, suggesting more light rail and bus rapid transit, making streets more pedestrian-friendly, adding more ridesharing company services, improving highways, and removing or covering highways that harm neighborhoods. The fourth list dealt with national and international transit, detailing modernizing JFK and Newark Airports, expanding seaports and freight railroads, and making the Northeast Corridor a fast, reliable railroad route. The RPA has a history of publishing plans that actually get built, unlike some other regional planning groups.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |