New York Port of Embarkation facts for kids

The New York Port of Embarkation (NYPOE) was a very important command for the United States Army. Its main job was to move soldiers and supplies from the United States to places overseas. This command had huge facilities in New York and New Jersey, covering much of what is now the Port of New York and New Jersey. It also had smaller ports in other cities under its control.

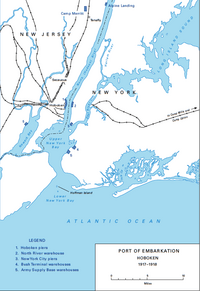

During World War I, this port was first known as the Hoboken Port of Embarkation. It was set up in buildings taken from a German shipping company in Hoboken, New Jersey. The Army's Quartermaster Corps was in charge back then. Smaller ports in Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even Canadian cities like Halifax and Montreal helped out. After World War I, the Hoboken port was closed, and operations moved to a new army terminal in Brooklyn.

Even between the wars, the idea of a "port of embarkation" continued. It served as the home base for Army ships in the Atlantic. When war started in Europe in 1939, the New York Port of Embarkation was formally brought back. It became the main port on the Atlantic coast, helping to create new ways to manage these huge operations.

In World War II, the NYPOE was managed by the new Transportation Corps. It was the biggest of eight such commands. The San Francisco Port of Embarkation was the second largest overall, and Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation was the second largest on the East Coast. At first, Charleston, South Carolina was a smaller sub-port under NYPOE, but it later became its own command. The cargo port in Philadelphia stayed under NYPOE's command throughout the war.

By the end of World War II, an amazing 3,172,778 passengers (including 475 from Philadelphia) and 37,799,955 tons of cargo had passed through the New York port. Its Philadelphia sub-port handled an additional 5,893,199 tons of cargo. This means the NYPOE moved about 44% of all troops and 34% of all cargo that went through Army ports during the war!

Contents

What is a Port of Embarkation?

The idea of a Port of Embarkation (POE) grew a lot from World War I to World War II. The NYPOE was the first and largest POE in World War I, so it became the model for how these ports should work. Even when the formal command was stopped after World War I, the main ideas and functions continued at the Army's big ports in Brooklyn and San Francisco.

When war began in Europe in 1939, New York was the only active port of embarkation on the Atlantic coast. As the United States got ready for war, other facilities became POEs or sub-ports. For example, New Orleans became a POE, and Charleston became a sub-port of New York.

An Army "Port of Embarkation" was much more than just a shipping dock. It was a complete system! It included a command structure, land transportation, supply centers, and housing for troops. All of this was designed to load ships efficiently for overseas travel.

The Army had rules (AR 55-75) that explained what a POE commander did. They were in charge of everything at the port:

- Receiving, supplying, and moving troops.

- Receiving, storing, and moving supplies.

- Making sure ships were ready for their missions.

- Managing military traffic between the port and overseas bases.

- Commanding all troops at the port, including those waiting to ship out.

- Giving instructions to people and groups moving through the port.

- Making sure troops and supplies moved smoothly.

A main POE could have smaller sub-ports or cargo ports, even in other cities. These could be used for specific movements to overseas commands. For example, in World War I, ports in Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even Canada were sub-ports to the NYPOE.

One special job was handling mail. The POE had to make sure all mailbags were labeled correctly and sent on the earliest possible ship. They also had to spread mail out so that if one ship was lost, not all mail for a unit would be destroyed.

For troop movements, the most important thing was having ships ready and knowing their sailing dates. To avoid delays, the POE controlled when troops moved from their home bases to the port. They also made sure troops were properly equipped and ready for overseas duty.

Most troops went to assembly points overseas. But if they were going to fight, the ports would "combat load" them. This meant troops and their equipment were loaded in a special way for efficient unloading during a battle. Combat teams would even stay together at the port.

The POE's command even extended to the troops and cargo once they were on the ships! This was done through "transport commanders" and "cargo security officers" on Army-controlled ships. These officers were appointed by and reported to the POE. Troops on all ships (except U.S. Navy transports) remained under the port commander's overall command until they arrived overseas. The transport commander was responsible for all passengers and cargo, but not for operating the ship itself.

World War I Operations

The Hoboken Port of Embarkation was officially started on July 27, 1917. The Army quickly realized that moving huge amounts of supplies and troops overseas for World War I needed a single, strong command. This new organization would report directly to the War Department in Washington, D.C..

The first headquarters was in Hoboken, New Jersey. It used piers and facilities that were taken from German shipping companies on the Hudson River. Major General David C. Shanks took command on August 1, 1917, and played a big role in its operations.

In the early days of World War I, cargo was handled in Brooklyn and New Jersey. Troops mostly moved out of Hoboken and nearby Manhattan piers that had passenger facilities.

By the end of the war, the NYPOE had grown huge. It had a staff of 2,500 officers, special camps for soldiers, hospitals, twelve piers, and seven warehouses in Hoboken. In Brooklyn, it had eight piers and 120 warehouses. It also had three piers in Manhattan.

Three large camps for troops came under the port's direct command:

- Camp Merritt could hold 38,000 temporary troops.

- Camp Mills could hold 40,000 troops.

- Camp Upton could hold 18,000 troops.

Camp Dix also served as an embarkation camp for the port. The command also included several hospitals for soldiers.

The ports of Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and the Canadian ports of Halifax, Montreal, and St. John's were all smaller sub-ports under the NYPOE.

The Army realized it needed a permanent, large facility for shipping. So, the Brooklyn Army Base (later called the Brooklyn Army Terminal) was built starting in 1918. It was located in Owls Head, Brooklyn, near Fort Hamilton.

The port managed the return of American soldiers from France after the war (1919) and from Germany (1919–1923). It also helped support forces in Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone. In December 1919, a ship called the USAT Buford transported 240 people, including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, who were considered Communists and radicals, from the NYPOE to Finland.

General Shanks' command and the NYPOE were officially stopped on April 24, 1920. Its jobs were given to the Army Transport Service at the Brooklyn Army Base. Even though the command changed, the terminal was still often called the New York Port of Embarkation.

Between the Wars

After World War I, the port became a place for supplies and personnel for overseas bases. It didn't have the same coordinating functions as before. It was managed by a Superintendent who reported to the Quartermaster General.

On May 6, 1932, the New York Port of Embarkation was officially reactivated. Its command was at the Army Base in Brooklyn. It combined the Atlantic branch of the Army Transport Service, the New York General Quartermaster Depot, and the Overseas Replacement and Discharge Service.

World War II Operations

Major General Homer M. Groninger took command on November 7, 1940, and stayed in charge throughout the war in Europe. He greatly expanded the port's role in supplying overseas commands. The NYPOE became the model for how other Army Ports of Embarkation would operate. Most of the basic system for handling requests from overseas, planning shipments, and loading cargo was developed there.

In 1939, when war broke out in Europe, NYPOE was the only active port of embarkation on the Atlantic. Before the United States entered the war, two sub-ports were set up under NYPOE:

- Charleston: This port was created to help ease the pressure on NYPOE. It mainly supported the West Indies and Caribbean areas. After the U.S. entered the war, Charleston became its own POE.

- New Orleans: This started as a sub-port to support the Panama Canal. Later, it helped support commands in the Caribbean, South Atlantic, and Pacific as the New Orleans Port of Embarkation.

By December 17, 1941, all depots and ports of embarkation came under the Chief of the Transportation Branch. Central control became very strict and coordinated. A Transportation Control Committee managed all movements of troops and freight, including Lend-Lease supplies, through the ports. This committee included all military services, the War Shipping Administration (WSA), and even the British Ministry of War Transport.

Later in the war, Boston and Hampton Roads became full ports of embarkation. A cargo sub-port under NYPOE was also set up in Philadelphia. Even with the success of other ports, NYPOE remained the single port with the most passengers and cargo. Only the San Francisco Port of Embarkation came close in its importance for supporting the war.

The biggest challenge for the command was the availability and movement of ships. This was coordinated with the port but not fully controlled by it. Troops and supplies had to be ready to meet ship schedules, convoy cycles, and sailing dates. Adjustments were often needed due to mechanical issues, weather, or other demands. Convoy schedules were controlled by the Navy, and all ship sailings needed Navy approval.

Major Facilities

Embarkation Camps

Embarkation camps were special areas where troops stayed and got ready for about one to two weeks before going overseas. At NYPOE in 1944, troops usually stayed between 7.1 and 11.7 days. These camps were directly under the Port Commander. Their job was to finish training, equip, and prepare troops, making sure they matched the troopship and convoy schedules.

Key camps included:

- Camp Kilmer in New Jersey: This camp could hold over 37,500 troops. Soldiers usually traveled by train to Jersey City, New Jersey, then took ferry boats to the piers to board their ships.

- Camp Shanks in Orangeburg, New York: Nicknamed "Last Stop USA," this camp could hold over 34,600 troops. About 1.3 million troops passed through here. They traveled by train to Jersey City or marched to Piermont, New York, then took a ferry to the piers.

- Fort Hamilton: This fort could hold 5,700 troops and was used when needed.

- Fort Slocum: This served as a training center for Transportation Corps officers and a staging area for NYPOE when needed.

Subports

Boston was a sub-port under New York until July 1942, when it became its own port. Philadelphia was set up and remained a cargo port under New York's command. About 475 passengers boarded ships in Philadelphia in 1943 and 1944, and their numbers were included in the NYPOE total. Philadelphia was very important for shipping explosives. Its original two explosives berths were expanded to six, matching New York's Caven Point terminal.

Terminals

The port had ten main terminals:

- Brooklyn Army Base: Located at 58th Street, Brooklyn, this was the headquarters. It had piers, 3.8 million square feet of storage, and train tracks for 450 rail cars.

- Bush Terminal: Near the Brooklyn Army Base, this terminal had eight piers, 1.5 million square feet of storage, and tracks for 150 rail cars.

- Staten Island Terminal: In Stapleton, this had ten piers, 4.5 million square feet of storage, tracks for 235 rail cars, and large outdoor storage areas.

- Howland Hook Terminal: On Staten Island, this handled petroleum products.

- Fox Hills: On Staten Island, this was a training area for Army Port Battalions and housing for port staff.

- Port Johnson: In Bayonne, New Jersey, this had open storage and was key for preparing combat vehicles for shipment.

- North River, Manhattan: This was the main place for troops to board ships. It had seven piers where troops arrived by ferry from rail terminals.

- Army Postal Terminal: This included an Army Post Office in Manhattan and a Postal Concentration Center in Long Island City. Most mail for the European Theater went through NYPOE. The port made sure mailbags were addressed correctly and loaded safely. During the Christmas rush of 1944, NYPOE handled about 2.6 million mailbags!

- Special Services Supply Terminal: With facilities in Brooklyn and Manhattan, this shipped items like 4 million magazines and 5 million booklets to troops overseas.

- Caven Point: In Jersey City, New Jersey, this was a facility for loading ammunition and explosives directly from rail cars onto ships. It was built as an expansion of the Lehigh Valley Railroad Claremont terminal.

Associated Facilities

- Camp Mitchel at Mineola.

- Camp Upton at Yaphank on Long Island.

- Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania: This was a Transportation Corps facility where port troops were trained, though not directly under NYPOE command.

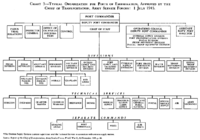

General Organization

By the end of the war, most ports had a similar structure:

- Overseas Supply Division: Handled supply requests from overseas, ordered supplies, and scheduled their movement to ships.

- Port Transportation Division: Managed troop and cargo movements to and within the port, coordinating loading and unloading.

- Troop Movement Division: Controlled troop movement through the port, including processing, housing, and coordinating with other divisions.

- Initial Troop Equipment Division: Managed the movement of equipment for units and oversaw the final outfitting of troops.

- Water Division: Responsible for loading/unloading vessels, their operation, maintenance, repair, and conversion. They also managed piers, docks, and marine repair shops.

Supply

Managing supplies was complex, especially with limited shipping space. Sometimes, the ports would load materials that weren't immediately needed just to fill available space. For example, NYPOE continued to send ammunition to North Africa even when it wasn't requested, leading to too much ammunition there in early 1943.

This issue was resolved in early 1943. Supply and transportation teams began working closely together under the Commanding General, Army Service Forces. Theater commands placed supply orders through the ports, a system largely developed at NYPOE. The supply schedule was tied to convoy sailings, which the Navy controlled. NYPOE coordinated with the Navy and managed supply movement from depots to ships, even coordinating with production schedules.

For storing materials, 60 temporary warehouses with over 3 million square feet of space were built at Fort Jay on Governors Island.

The Army was responsible for most explosives shipping, including large bombs for its air forces and Lend-Lease shipments to Britain and the Soviet Union. New York was a key point for this. Due to past disasters like the Black Tom explosion in Jersey City, there was great concern about handling such dangerous cargo. When the Navy took over the terminal at Bayonne, the Army had to build an explosives terminal closer to Manhattan at Caven Point. Work began in August 1941 and finished in June 1942. Despite safety efforts, there was an incident at Caven Point where the ship El Estero caught fire and had to be sunk in the harbor. To reduce the concentration of munitions at NYPOE, the Army expanded Philadelphia's munitions capability and spread out these facilities among all ports.

Troop Movements

Just like with supplies, the most important factor for troop movements was having ships ready and knowing their sailing dates. To avoid delays, NYPOE controlled troop movements from their home bases to the port. The port had the final responsibility to ensure troops were properly equipped and ready for overseas deployment.

Large troop movements were kept secret to prevent sabotage and to avoid alerting enemies about big ship sailings. After some early problems, strict secrecy was put in place. Details were shared through secure communications between the Army's Traffic Control Division, the port, and Army railroad stations.

A complicated part of preparing troops was matching them with equipment not issued at their home base. This equipment arrived at the port from specialized depots or even manufacturers. The NYPOE even made a film showing the important steps for "Preparation for Overseas Movement." About a week before departure, the overseas destination was told generally about the troops expected on a ship. Once the ship sailed, the destination received a "sailing cable" with the actual date and an airmailed list of the final troops and cargo.

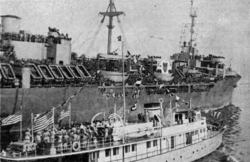

Other military services and civilians traveling on Army-controlled ships were also handled by the port. For example, a Navy group (SNAG 56) traveled by train from Long Island to Jersey City, then took a ferry to Pier 86 in Manhattan. There, they boarded the Aquitania (NYPOE code "N.Y. 40") on January 29, 1944, with about 1,000 Navy and 7,000 Army personnel, arriving in Greenock, Scotland on February 5.

Other Functions

Staging Areas

The embarkation camps, or staging areas, were a key part of the port. They became very important because it was decided not to send troops directly from their home bases to the ships. The main reason was to make sure ships, which were in short supply, didn't leave empty or delayed. Having troops at the port before departure was crucial. Also, the port was responsible for making sure units were at full strength, healthy, and fully equipped before boarding. They even had replacement pools for missing or unfit troops. Command of the troops passed to the port commander once they arrived at the staging area, and then to the port's transport commander until they arrived overseas. These camps were also used for returning troops and prisoners of war.

Medical

The port was responsible for final medical checks in the staging areas. This included physical exams to find infectious diseases that could spread on crowded troop ships or other conditions that would make a person unfit for overseas duty. The ports, working with the Medical branch, tried to make troops fit for duty if they had minor issues, providing medical care, dental care, and even eyeglasses.

In spring 1943, NYPOE issued instructions for transport surgeons (Medical Corps officers on the transport commander's staff). These instructions detailed the care of both arriving and departing troops and their responsibilities for transferring patients from ships to the port. By the end of 1943, all ports adopted these instructions.

Early in the war, wounded soldiers from Atlantic war zones were brought back to the U.S. on returning troop ships. Transport surgeons sent patient lists to the port commander before arrival. When the ship arrived, NYPOE was responsible for unloading patients and sending them to hospitals like Tilton General Hospital or Lovell General Hospital. If needed, patients stayed in the port's own hospitals during waiting periods. The port continued to handle patients returning on regular transports even after special hospital ships began operating.

Ship Maintenance and Conversion

One of the port's jobs was maintaining Army transports and planning changes to them, including converting them into hospital ships. Plans for converting six Liberty ships were made by naval architects. The rest of the ship plans were done by the Maintenance and Repair Branch of the Water Division, working with the Surgeon General's Office.

Debarkation, Redeployment, and Repatriation

After VE Day (Victory in Europe Day), the port also became a place for people to arrive. Before VE Day, this was a smaller operation, mostly for members of other services, Allied forces, civilians, and prisoners of war. Throughout the war, patients had been returned home by troop ships and later hospital ships, with the port responsible for getting them off the ships and to hospitals.

After the war in Europe ended, the port's job shifted from sending troops overseas to receiving them back home. General Groninger was transferred to command the San Francisco Port of Embarkation. The priority was to send troops directly from Europe to the Pacific. However, many troops returned to the U.S. Some would get leave, some would leave the service, and others would head to the Pacific. The Pacific war ended unexpectedly quickly, so the focus shifted to bringing troops and even the remains of those killed back home. This created even more traffic than during the war. The ports were responsible for processing units for inactivation. On April 11, 1945, a conference was held at NYPOE about the big changes Atlantic ports would need to make.

Accomplishments

The NYPOE was by far the largest of the Army Ports of Embarkation. By the end of 1944, besides the embarkation camps, it controlled:

- Piers with berths for 100 ocean-going ships.

- 4,895,000 square feet of transit shed space.

- 5,500,000 square feet of warehouse space.

- 13,000,000 square feet of open storage and working space.

By August 1945, 3,172,778 passengers and 37,799,955 tons of cargo had passed through NYPOE. Its Philadelphia cargo sub-port handled an additional 5,893,199 tons of cargo. The total for all Army ports was 7,293,354 passengers and 126,787,875 tons of cargo. This means the NYPOE handled 44% of all troops and 34% of all cargo that went through Army Ports of Embarkation!

During the war, 85 percent of men and materials going to the European theater passed through the NYPOE.

One amazing example of its speed happened on July 13, 1942. The British urgently needed tanks and artillery to fight Rommel after the fall of Tobruk. A convoy of six fast cargo ships was loaded at NYPOE with armor and ammunition for Egypt. When one ship, the SS Fairport, was sunk, NYPOE found replacement armor and ammunition. They loaded and sent the Seatrain Texas within 48 hours! This ship sailed alone and arrived in Suez in time for its cargo to help defend Cairo.

Post War

The New York Port of Embarkation continued its operations under the Chief of Transportation. The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation became a sub-port on March 31, 1954. On September 28, 1955, the New York Port of Embarkation was renamed the Atlantic Transportation Terminal Command, Brooklyn, starting October 1. Its headquarters were at the Brooklyn Army Base. This new command was responsible for all Army terminal activities on the Atlantic coast, from Canada south to Miami, Florida. The Brooklyn Army Base itself was separated and renamed the Brooklyn Army Terminal. On April 1, 1965, the Brooklyn Army Terminal and other remaining facilities of the old ports of embarkation were transferred to the Military Traffic Management and Terminal Service.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |