Commissioners' Plan of 1811 facts for kids

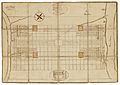

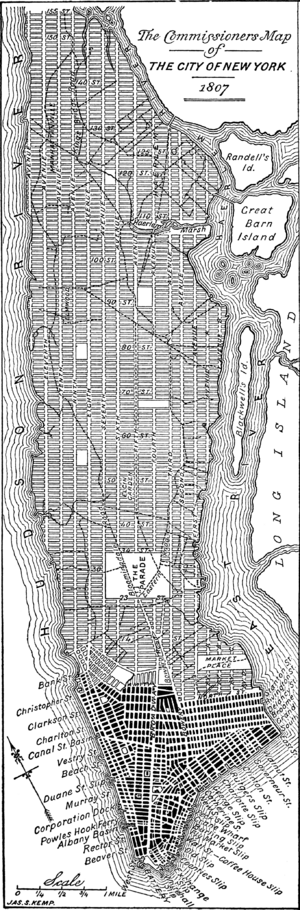

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 was the first design for the streets of Manhattan. It covered the area from Houston Street up to 155th Street. This plan created the rectangular grid plan of streets and building lots that Manhattan still uses today. People have called it "the single most important document in New York City's development." The plan was designed to bring "beauty, order and convenience" to the city.

The idea for the plan came from the Common Council of New York City. They wanted to organize the land in Manhattan between 14th Street and Washington Heights. But they faced political issues and objections from landowners. So, they asked the New York State Legislature for help. In 1807, the legislature appointed a special group called a commission. This commission had a lot of power, and they presented their plan in 1811.

The Commissioners were Gouverneur Morris, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States; John Rutherfurd, a lawyer and former U.S. Senator; and Simeon De Witt, the state's top surveyor. Their main surveyor was John Randel Jr., who was only 20 years old when he started this big job.

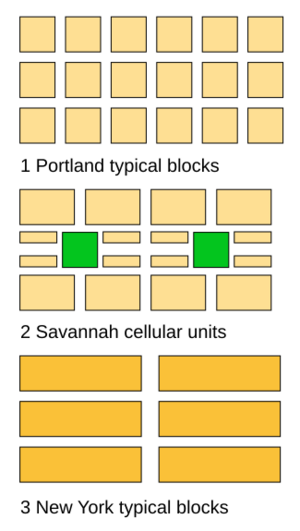

The Commissioners' Plan is probably the most famous example of a grid plan or "gridiron" layout. Many historians see it as a very important and forward-thinking idea. While some people have criticized the plan for being boring and too strict, urban planners today often view it more positively.

The plan did include a few public spaces. One was the Grand Parade, a large open area between 23rd and 33rd Streets. This later became Madison Square Park. There were also four other squares and a market complex. Central Park, the huge green space in Manhattan, was not part of this original plan. It was only thought of much later, in the 1850s.

Contents

What is a Grid Plan?

A grid plan is a city layout where streets cross each other at right angles, like a checkerboard. This design is very old and has been used in cities around the world for thousands of years.

History of Grid Cities

Grid layouts have been found in Ancient Egypt and in cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley. Some historians think the grid plan was invented there. The Greek city of Miletus was rebuilt on a grid plan after being destroyed. Hippodamus of Miletus, often called "the father of European urban planning", helped spread this idea in Greece.

The Romans also used grid plans for their military camps. Many of these camps later grew into towns and cities. Pompeii is a great example of a Roman city built with a grid system. This idea spread across Europe during the Renaissance.

In the United States, the grid plan is very common. Spanish cities like St. Augustine, Florida and Santa Fe, New Mexico used grids. French settlers also built New Orleans on a grid. Some early English colonial cities like Philadelphia and Savannah, Georgia were also designed with grids from the start. For example, William Penn planned Philadelphia's grid in 1682.

By the late 1700s, the grid plan was well-known in the U.S. The federal Land Ordinance of 1785 even required new states in the west to have straight borders and be divided into rectangles. This led to many American cities like Anchorage, Alaska and Miami using grid layouts.

Grid sizes can vary a lot. Carson City, Nevada, has very small blocks, while Salt Lake City has much larger ones. A common size is a 300-foot square block with streets 60 to 80 feet wide.

How New York City's Streets Grew

The streets in lower Manhattan grew without much planning. They were a mix of country paths, short streets, and old Native American trails. These paths were shaped by history and land ownership, not by a grand design. Around 1800, the Common Council of New York started to take control. They made rules to keep streets clear and required new streets to be approved.

Early Grid Ideas

Before the Commissioners' Plan, some private landowners tried to create grids in New York.

- In the 1750s, Trinity Church planned a small grid near King's College (now Columbia University).

- In the 1760s, the De Lancey family laid out a grid of streets around "De Lancey Square." Even after their land was taken after the American Revolution, these streets remained. They became important streets in the Lower East Side.

- In 1788, the Bayard family hired a surveyor to plan streets on their land west of Broadway. These streets are now part of SoHo and Greenwich Village.

- Petrus Stuyvesant, a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, also planned a small grid for his estate. Only one street from his plan, Stuyvesant Street, was actually built. It is still the only street in Manhattan that runs almost perfectly east-west.

Surveying the Common Lands

The city owned a lot of land in the middle of Manhattan, called the Common Lands. This land was not good for farming and was hard to reach. To sell it, the city hired surveyor Casimir Goerck in 1785. He divided the land into lots and planned roads. His work was not a perfect grid, but it was a step towards one. He created a middle road that later became Fifth Avenue.

In 1794, Goerck surveyed the area again, making the lots more uniform. He also planned roads to the west and east of the middle road. These later became Fourth and Sixth Avenues. His cross streets became the numbered east-west streets of the future plan. Goerck's work was difficult because of the rocky and swampy land. But his surveys were the foundation for the Commissioners' Plan.

The Mangin–Goerck Map

In 1797, the city asked Goerck and another surveyor, Joseph-François Mangin, to map Manhattan's streets. Goerck died during the project, but Mangin finished it. The map, presented in 1803, showed not only existing streets but also where Mangin thought future streets should go. It included new grids and parks.

The city council first accepted this map. But later, due to political reasons, they said it was inaccurate. They even tried to buy back copies of the map. However, as the city grew, Mangin's ideas for future streets were often used anyway. When the Commissioners' Plan came out in 1811, it was very similar to Mangin's ideas for the undeveloped areas.

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811

The city council wanted a clear plan for New York's growth. They hoped to improve public health by organizing the city. At the time, people believed bad air caused diseases.

In 1807, the state legislature appointed the three Commissioners: Gouverneur Morris, John Rutherfurd, and Simeon De Witt. They were given special power to plan streets, roads, and public squares in Manhattan north of Houston Street. They had four years to survey the island and create a map. Streets had to be at least 50 feet wide, and main avenues at least 60 feet wide.

The Commissioners decided on a simple grid plan. They believed straight streets and right-angled buildings were the cheapest and most convenient. This choice also fit the idea of equality in the new American republic.

Surveying the Island

The Commissioners needed an accurate map of Manhattan. Their first surveyor, Charles Frederick Loss, was not very good. So, in 1808, John Randel Jr. took over. He was only 20, but he was very skilled.

Randel spent years mapping the island's hills, swamps, and existing features like houses and fences. He also precisely located Goerck's earlier roads. This helped the Commissioners decide where to place their new grid. Randel faced lawsuits from landowners who didn't like surveyors on their property. The state legislature passed a law in 1809 to protect the surveyors, requiring the city to pay for any damages.

By late 1810, the Commissioners had decided on the grid plan. Randel then drew the final maps, which were huge, almost nine feet long when put together. His work was praised for its accuracy.

The Plan Details

The Commissioners published their plan in March 1811. It included a large map and a pamphlet. The grid had 12 main north-south avenues and many cross streets. The grid was tilted 29 degrees east of true north, matching the angle of Manhattan island. This simple rectangular layout was chosen because it was practical and easy to build on.

The avenues were numbered from First Avenue in the east to Twelfth Avenue in the west. Some avenues, like Twelfth Avenue, were planned for land that didn't exist yet but would be created by filling in the rivers. Broadway, an existing road, was not part of the original grid but was added later.

There were 155 numbered cross streets running east-west. They were 60 feet wide, with about 200 feet between each pair of streets. This created about 2,000 long, narrow blocks. Fifteen of these cross streets, like 14th and 42nd Streets, were made 100 feet wide.

The blocks between avenues were not all the same width. They were shorter near the Hudson and East River waterfronts. The Commissioners expected more businesses and development there, as water transport was important. The avenues were wide enough for horse-drawn vehicles.

Manhattan's blocks are long rectangles, longer east-west than north-south. This was different from the square grids in many other cities. The grid made land easier to buy and sell in equal-sized units.

Public Spaces

The plan included very few parks or public squares. The main one was the Grand Parade, a large military drill ground. It was later reduced and became Madison Square Park.

Other smaller squares were planned, like Manhattan Square, which is now Theodore Roosevelt Park around the American Museum of Natural History. Most of the other planned public spaces were either reduced or removed over time. For example, a large market complex in the East Village was scrapped, though part of it later became Tompkins Square Park.

The Commissioners believed the public would always have access to the Hudson and East Rivers. They thought this made large inland parks unnecessary. However, over time, docks and buildings blocked river access until much later.

Changes and Extensions

Over the years, the original 1811 grid has been changed many times. By 1865, 38 state laws had modified it.

Central Park and Other Changes

The biggest change to the plan was the creation of Central Park. This huge park, covering 843 acres, was built between 59th and 110th Streets and Fifth and Eighth Avenues.

People started discussing the need for a large park in the 1840s. They felt New York needed parks like those in London and Paris. In 1853, the state allowed the city to buy the land for the park. Construction began in 1857. The park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

Andrew Haswell Green, who led the Central Park Commission, was a critic of the grid. He managed to make changes to the grid above 59th Street. He created Morningside Park and Riverside Park, which follow the natural hills. He also laid out a wide "Boulevard" (now Broadway) on the West Side.

Because there was no single group protecting the original plan, other changes happened. The Grand Parade and the marketplace were removed. New squares like Union, Tompkins, and Stuyvesant were added. Lexington and Madison Avenues were also added later.

Many other buildings and places also interrupt the grid today. These include college campuses like Columbia University, hospitals, churches, housing projects, and major transportation hubs like Grand Central Terminal.

Above 155th Street

The 1811 plan stopped at 155th Street. As New York City grew, a plan was needed for Upper Manhattan. This area had very steep hills and deep valleys, making a simple grid difficult.

In 1860, a new commission was formed to plan Upper Manhattan. They wanted a plan that respected the natural landscape, not just a grid. However, due to pressure from businesses, the plan they created in 1863 mostly extended the original grid. By 1865, Andrew Haswell Green's Central Park Commission took over this task.

Green's commission studied the area carefully. In 1868, they published a plan that included grids in the valleys but also streets and parks that followed the land's natural shape. This is why Upper Manhattan looks different from the grid below 155th Street. New avenues like Riverside Drive and Saint Nicholas Avenue were added.

The Bronx

As New York City expanded into the Bronx in the late 1800s, the street numbering system also extended there. However, it wasn't always uniform. Some areas used existing street systems, and the spacing between streets was different from Manhattan.

Avenues and Streets Today

Most of the east-west streets from the Commissioners' Plan are still there, except for those replaced by Central Park. While some streets are blocked by parks or buildings, the east-west grid is largely intact.

The north-south avenues have changed more. Their number has increased, and many have been renamed.

- In the 1830s and 40s, Lexington Avenue and Madison Avenue were added. These were needed because the original plan left large gaps between some avenues.

- Only First, Second, Third, and Fifth Avenues, and Avenues C and D, have kept their original names.

- Sixth Avenue was renamed "Avenue of the Americas" in 1945, but most New Yorkers still call it Sixth Avenue.

- Other avenues like Fourth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Avenues have also been renamed in parts.

Broadway

Broadway was originally a main road in the colonial city. It ended at 10th Street and then became the Bloomingdale Road, which wound its way north. The Commissioners' Plan initially kept Broadway but intended to remove the uptown sections. However, Bloomingdale Road was gradually restored and straightened over time. By 1899, the entire road was named Broadway.

Broadway's angled path below 59th Street creates famous public spaces like Times, Herald, Madison, and Union Squares. These are sometimes called "happy accidents" because they weren't planned.

How People Felt About the Plan

The Commissioners' Plan received mixed reactions from the start.

Criticism

Many people criticized the plan. They said it ignored the island's natural hills and valleys. They also thought it was boring and lacked beauty. Some believed it was only made for making money.

- Writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Alexis de Tocqueville found it "monotonous."

- Poet Walt Whitman called the straight streets and right angles "the last thing in the world consistent with beauty."

- Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed Central Park, was a big critic. He joked that the grid might have been created by placing a mason's sieve on a map. He also said that New York was "unfortunately planned" and would become "monotonous straight streets."

- Clement Clarke Moore, author of "Twas the Night Before Christmas," strongly objected. He said the plan destroyed nature and was a "tyranny." However, he later made a lot of money developing his own land using the grid.

- Writer Henry James complained about New York's "inconceivably bourgeois scheme" and its lack of "stately square or goodly garden."

- Architect Julius Harder said the plan ignored "economy of intercommunication, future financial economy, sanitation, healthfulness and aesthetics."

- Historian Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes felt the plan lacked "sentiment and charm" and destroyed Manhattan's "primitive beauty."

- Architecture critic Lewis Mumford called it "blank imbecility" and a "straight-jacket."

- Urban activist Jane Jacobs noted the "endless amorphous repetitions" of the streets.

- French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre felt "lost" in the "numerical anonymity of streets and avenues."

Praise

Despite the criticism, many people praised the grid plan.

- In 1814, the Citizens and Strangers Guide called it "an important legacy to posterity."

- An official in 1836 said the plan was "magnificent" and showed "prophetic views" for the city's growth.

- Legal scholar James Kent called the plan "brilliant" and a "monument of the stability and wisdom of the measure."

- Diarist George Templeton Strong loved how the city was "marching northward" and how "wealth is rushing in."

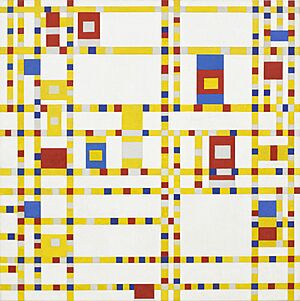

- Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas called the grid "the most courageous act of prediction on Western civilization." He said it created "undreamed-of freedom for three-dimensional anarchy" and made "all previous lessons of urbanism irrelevant."

- Modernist architect Le Corbusier liked the "right-angled intersections."

- Architect Wendy Evans Joseph said the grid "embodies something uniquely American, a democratic transparency."

- Uruguayan architect Rafael Viñoly called it "the best manifestation of American pragmatism." He said it allowed "mediocrity to coexist with greatness."

- Niels Gron, a Danish observer in 1900, argued that New York's purpose was power and magnificence, not traditional beauty.

- Journalist James Traub said the grid's "utilitarian street plan has made possible the helter-skelter, pell-mell life of the city."

- Hilary Ballon, a curator, noted the grid's "remarkable flexibility" over 200 years. She said it makes the city easy to navigate and serves as a "metaphor for the openness of New York itself!"

- Author David Owen wrote that grid plans are "self-explanatory" and make walking in Manhattan "like walking on a map."

- Economist Edward Glaeser said the grid "imposes clarity" and makes the city "manageable."

- Architect Lance Hosey pointed out that the grid is well-adapted to its setting. Because it's tilted, "every building on every street can receive direct daylight every day of the year."

- French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote that New York's geometry makes "each individual... 'poetically' the owner of the capital of the world."

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 shaped Manhattan into the famous city it is today. It created a clear, organized framework that allowed for massive growth and change, even if it wasn't always seen as beautiful.

Images for kids

-

Central Park is the largest interruption of the Commissioners' grid.

-

Theodore Roosevelt Park, part of Central Park, is the only planned public space from the Commissioners' Plan that still exists.

-

Frederick Law Olmsted, a strong critic of the Commissioners' Plan (around 1860).

-

Clement Clarke Moore objected to the Plan, but later made money from it (1897).

-

Henry James (1910).

-

Jean-Paul Sartre (around 1950).

-

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (1987).

-

Rafael Viñoly (2011).

See also

In Spanish: Plan de los Comisionados de 1811 para niños

In Spanish: Plan de los Comisionados de 1811 para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |