Roland Barthes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

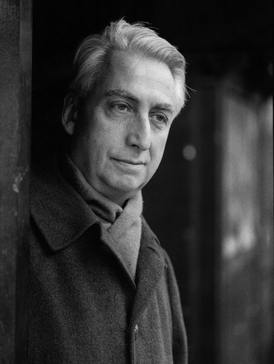

Roland Barthes

|

|

|---|---|

Roland Barthes

|

|

| Born |

Roland Gérard Barthes

12 November 1915 |

| Died | 26 March 1980 (aged 64) |

| Education | University of Paris (BA, MA) |

|

Notable work

|

Writing Degree Zero (1953) Mythologies (1957) The Death of the Author (1967) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Structuralism Semiotics Post-structuralism |

| Institutions | École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Collège de France |

|

Main interests

|

Semiotics (literary semiotics, semiotics of photography, comics semiotics, literary theory), narratology, linguistics |

|

Notable ideas

|

texte Lisible vs texte texte scriptible Structural analysis of narratives Effect of reality |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Roland Gérard Barthes (born November 12, 1915 – died March 26, 1980) was a French writer, philosopher, and semiotician. He studied how different "sign systems" work, especially in everyday popular culture. His ideas helped shape many areas of study, like structuralism (looking at how things are built) and post-structuralism (questioning those structures).

Barthes is famous for his book Mythologies (1957), which looked at popular culture. He is also known for his essay "The Death of the Author" (1967). This essay changed how people thought about literary criticism (studying books). He taught at important schools in France, like the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and the Collège de France.

Contents

About Roland Barthes

Early life and education

Roland Barthes was born on November 12, 1915, in Cherbourg, Normandy, France. His father, Louis Barthes, was a naval officer who died in World War I before Roland's first birthday. Roland was raised by his mother, Henriette Barthes, along with his aunt and grandmother. They lived in the village of Urt and the city of Bayonne. In 1924, his family moved to Paris.

Barthes was a very bright student. From 1935 to 1939, he studied at the Sorbonne. He earned a degree in classical literature. During these years, he often suffered from tuberculosis, a serious illness. This meant he had to spend time in special hospitals called sanatoria. His health problems sometimes stopped him from finishing his studies and taking exams. Because of his health, he did not have to serve in the military during World War II.

From 1939 to 1948, he continued his studies, focusing on grammar and philology (the study of language in historical texts). He also published his first writings. In 1941, he received another degree from the University of Paris for his work on Greek tragedy.

Starting his career

In 1948, Barthes began working in academics again. He held several short-term jobs in France, Romania, and Egypt. During this time, he wrote for a newspaper in Paris called Combat. This led to his first full book, Writing Degree Zero, published in 1953.

In 1952, Barthes joined the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. Here, he studied words and how societies work. For seven years, he wrote a popular series of essays for a magazine called Les Lettres Nouvelles. In these essays, he looked closely at the "myths" of popular culture. These essays were later collected in his famous book Mythologies, published in 1957.

Mythologies had 54 short essays, mostly written between 1954 and 1956. They were sharp observations about French popular culture. He wrote about everything from soap to wrestling. In 1957, Barthes taught at Middlebury College in the United States. He met Richard Howard there, who would later translate many of his books into English.

Becoming well-known

In the early 1960s, Barthes explored semiology (the study of signs) and structuralism. He held different teaching jobs across France and wrote more books. Many of his ideas challenged the usual ways of studying literature. This led to a disagreement with Raymond Picard, a well-known literature professor. Picard criticized Barthes's new ideas, saying they were unclear and didn't respect French literature. Barthes replied in his book Criticism and Truth (1966). He argued that the old way of criticism ignored language and new theories like Marxism.

By the late 1960s, Barthes was famous. He traveled to the United States and Japan, giving talks. During this time, he wrote his most famous essay, "The Death of the Author" (1967). This essay was important because it explored new ideas about how we understand texts.

Later work

Barthes continued to write for an avant-garde (new and experimental) literary magazine called Tel Quel. In 1970, he wrote S/Z, a detailed study of Balzac's story Sarrasine. Throughout the 1970s, Barthes kept developing his ideas about literary criticism. He thought about new ways to understand texts and how stories are told. In 1971, he was a visiting professor at the University of Geneva. He was mainly connected with the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

In 1975, he wrote a book about his own life called Roland Barthes. In 1977, he was chosen to lead the study of literary semiology at the Collège de France. That same year, his mother, Henriette Barthes, passed away at age 85. They had lived together for 60 years, and her death deeply affected him. His last major book, Camera Lucida, is partly about photography and partly a reflection on pictures of his mother.

Death

On February 25, 1980, Roland Barthes was hit by a laundry van in Paris. A month later, on March 26, he died from his injuries.

Barthes's ideas

Early thoughts on writing

Barthes's first ideas were a response to existentialist philosophy, which was popular in France in the 1940s. He especially reacted to Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre believed that both old and new ways of writing made readers feel distant. Barthes wanted to find what was truly unique and creative in writing.

In Writing Degree Zero (1953), Barthes said that language and style follow certain rules. So, neither is completely new or creative on its own. Instead, the truly creative act is how a writer chooses to use these rules to get a certain effect. He called this "writing." However, once a writer's style is shared, it can become a new rule itself. This means that being creative is a constant process of change and new reactions.

Semiotics and myths

Barthes's essays in Mythologies (1957) often looked at specific cultural things. He wanted to show how society used these things to spread its values. For example, he looked at how wine was presented in French society. It was often described as a healthy habit, even though it can be unhealthy.

He found semiotics, the study of signs, very helpful. He developed a theory to show how this "deception" worked. He said that myths create two levels of meaning. The first level is the direct, literal meaning (like a picture of a bottle of wine). The second level is the hidden, cultural meaning (like the idea that wine means a healthy, relaxing experience). Barthes called these hidden meanings "second-order signs" or "connotations." These ideas connected Barthes to similar Marxist theories.

In The Fashion System, Barthes showed how words could also be loaded with these hidden meanings. For example, if a fashion magazine says a "blouse" is perfect for a certain look, this idea quickly becomes accepted as truth. Barthes realized that his Mythologies became popular, and people started asking him to explain cultural things. This made him wonder if trying to "demystify" culture for everyone was truly useful. It pushed him to search for more individual meaning in art.

Structuralism and its limits

As Barthes studied structuralism, he focused on how important language is in writing. He felt this was often ignored by older critics. In his "Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative," Barthes looked at how a story's structure is like a sentence's structure. He divided stories into three levels: 'functions', 'actions', and 'narrative'. 'Functions' are small parts, like a descriptive word. That word helps create an 'action', which is a character. These 'actions' then make up the 'narrative'. This allowed Barthes to see how certain words help form characters. For example, words like 'dark' or 'mysterious' can create a certain type of character. By breaking down a story this way, Barthes could see how realistic the story was.

While Barthes found structuralism useful, he didn't think it could be a strict science. In the late 1960s, new ideas like post-structuralism and deconstruction (from Jacques Derrida) challenged structuralism. Derrida pointed out that structuralism relied on a "transcendental signifier"—a symbol with a constant, universal meaning. Without such a fixed point, a system that only looks at the work itself couldn't be truly useful. But since there are no truly universal symbols, the idea of structuralism as a way to judge writing was seen as flawed.

The "Death of the Author"

These thoughts led Barthes to think about the limits of signs and symbols, and how Western culture relies on ideas of things being constant. He traveled to Japan in 1966 and wrote Empire of Signs (1970). In this book, he reflected on how Japanese culture seemed okay with not searching for a single, ultimate meaning. He noticed that in Japan, there wasn't one big central point to judge everything by. He described the Emperor's Palace in Tokyo as quiet and not a huge, powerful symbol. Barthes felt that in Japan, signs could exist for their own sake, with only their natural meaning. This was very different from the society he wrote about in Mythologies, where things always had deeper, more complex meanings added to them.

After this trip, Barthes wrote his most famous essay, "The Death of the Author" (1968). Barthes believed that thinking about the author's intentions forced a single, ultimate meaning onto a text. But he argued that language has many meanings, and we can never truly know what an author was thinking. So, trying to find one "ultimate explanation" for a book is impossible. He felt that the idea of a "knowable text" was just another illusion of Western culture. He also thought that giving a book one final meaning made it like a product to be used up and replaced. "The Death of the Author" is seen as a post-structuralist work because it moved beyond simply trying to measure literature. Barthes said, "the death of the author is the birth of the reader."

Readerly and writerly texts

Since Barthes believed that the author's intentions don't give a text its meaning, he wondered where meaning comes from. He decided that meaning is actively created by the reader through analyzing the text. In his book S/Z (1970), Barthes applied this idea to a story by Balzac called Sarrasine. He found that the story had many possible meanings, but it was also limited by its strict order of events.

From this, Barthes said that an ideal text is "reversible," meaning it's open to many different interpretations. A text can be reversible by avoiding things that limit meaning, like strict timelines. He called this the difference between a "writerly text" and a "readerly text." In a writerly text, the reader is active and creative. In a readerly text, the reader just reads passively. This helped Barthes understand what he wanted from literature: openness to interpretation.

Photography and his mother

Barthes was always interested in photography and its ability to show real events. In his Mythologies essays, he showed how photos could have hidden meanings and be used to suggest "natural truths." But he still thought photos had a special power to show a truly real image of the world.

When his mother, Henriette Barthes, died in 1977, he started writing Camera Lucida. He wanted to explain why a picture of her as a child was so important to him. He thought about the obvious meaning of a photo (which he called the studium) and the purely personal feeling it gives someone (which he called the punctum). He realized that a photo creates a false idea of "what is," when "what was" is more accurate. His mother's childhood photo showed "what has ceased to be" because she had died. This made the photo uniquely personal to him, reminding him of his constant feeling of loss. Camera Lucida was one of his last works. It was a deep look at how personal feelings, meaning, and culture connect, and a touching tribute to his mother.

Impact and legacy

Roland Barthes's ideas helped develop important ways of thinking like structuralism, semiotics, and post-structuralism. His influence is found in many areas that deal with how information is shown and how we communicate. This includes computers, photography, music, and literature.

Because Barthes's work was always changing and questioning fixed ideas, there isn't one single "Barthesism" or group of followers who think exactly like him. Instead, his legacy is about encouraging people to always question and explore new ways of understanding the world.

Key ideas explained

Readerly text

This is a text that doesn't ask the reader to create their own meanings. The reader can just find meanings that are already there. Barthes said these texts follow a rule of "no contradiction." They don't challenge what people commonly believe or the "Doxa" (the usual way of thinking) of a culture. Most classic books are "readerly texts." They are like a cupboard where meanings are neatly stored away.

Writerly text

This is a text that aims to make the reader active, not just a consumer. It wants the reader to "produce" or create their own meanings. Barthes believed that we should never just accept culture and its texts as they are. Unlike "readerly texts" which are like products, the "writerly text" is like us writing. It's open to many different ways of understanding, not limited by one single idea or system. So, for Barthes, reading becomes a "form of work" where the reader is actively involved.

The Author and the Scriptor

Barthes used the terms "Author" and "scriptor" to describe different ways of thinking about who creates texts. The "Author" is the traditional idea of a single genius who creates a work from their own imagination. Barthes felt this idea was no longer useful.

Instead of the Author, Barthes introduced the "scriptor." A scriptor's only power is to combine existing texts in new ways. Barthes believed that all writing uses ideas, rules, and styles that already exist. He said the scriptor has no past; they are "born with the text." This means the writer's life story is less important than the text's own rules and traditions. Barthes argued that without the idea of an "author-God" controlling meaning, readers have much more freedom to interpret a work. He famously said, "the death of the author is the birth of the reader."

Criticism

In 1964, Barthes wrote an essay called "The Last Happy Writer," referring to Voltaire. In it, he talked about the challenges for modern thinkers who realize that ideas and philosophies are not always absolute. However, some, like Daniel Gordon, felt that Barthes completely misunderstood Voltaire.

The writer Simon Leys criticized Barthes's diary from a trip to China. Leys said Barthes seemed not to care about the Chinese people's situation. He also suggested that Barthes managed to "say nothing at great length" in his writings.

See also

In Spanish: Roland Barthes para niños

In Spanish: Roland Barthes para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |