Greek tragedy facts for kids

Greek tragedy is one of the three main types of plays from Ancient Greece, along with comedy and the satyr play. This style of drama became very popular in Athens during the 5th century BC. The plays from this time are often called Attic tragedy.

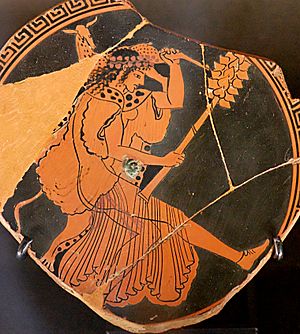

Greek tragedy started as part of festivals honoring Dionysus, the god of wine and theatre. These plays had a big influence on the theatre of Ancient Rome and later, the Renaissance. The stories in tragedies were usually based on old myths and epic poems. But instead of just being told, these stories were brought to life by actors on a stage.

The three most famous writers of Greek tragedies were Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Their plays explored big questions about human nature and life. This helped the audience connect with the stories and think about their own lives.

Contents

- What Does 'Tragedy' Mean?

- The Start of Greek Tragedy

- The Three Great Tragedians

- How a Greek Tragedy Was Structured

- A Big Event for the Whole City

- Famous Surviving Plays

- Ideas About Greek Tragedy

- Greek Tragedy as a Big Event

- The Tragedies We Still Have

- How Actors Connect with the Audience

- Greek Tragedy as a Performance

- Deus Ex Machina: A Special Trick

- Aeschylus: Connecting with Characters

- Images for kids

- See also

What Does 'Tragedy' Mean?

The word tragedy comes from the Greek word tragōidía. This word is made of two parts: tragos, which means "goat," and ōidē, which means "song." So, tragedy literally means "goat-song."

No one is completely sure why it was called this. One popular idea comes from the philosopher Aristotle. He thought tragedy grew out of songs and dances performed by a chorus dressed as satyrs, who were mythical creatures that were half-man and half-goat.

Another idea is that the word came from the prize given at early play competitions. The legendary first actor, Thespis, might have won a goat for his performance. Over time, the name stuck.

The Start of Greek Tragedy

From Songs to Plays

According to Aristotle, tragedy began with the dithyramb. This was a special hymn sung and danced by a large chorus of men and boys to honor Dionysus. At first, these performances were wild and fun, much like a satyr play.

Over time, the dithyramb became more serious. A huge change happened when a person named Thespis stepped out from the chorus and began speaking as a character. He became the very first actor. The Greek word for actor, hypokrites, means "answerer," because the actor would answer the songs of the chorus. This created a dialogue and turned the song into a story.

Tradition says Thespis was the first person to act out a character in a play in 534 BC. This was during a big festival in Athens called the Dionysia.

Early Playwrights

After Thespis, other writers began creating tragedies. A playwright named Phrynichus was one of the first to use stories from history in his plays, not just myths. He also added female characters to the stage for the first time. Around this time, playwrights also started writing plays in groups of three, called a trilogy.

The Three Great Tragedians

The most important and famous writers of Greek tragedy were Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Most of the surviving Greek tragedies were written by them.

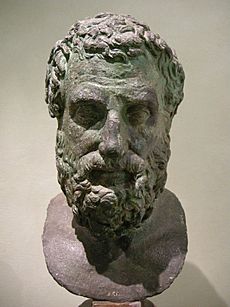

Aeschylus: The Father of Tragedy

Aeschylus made some of the biggest changes to tragedy. He is most famous for adding a second actor to the stage. Before Aeschylus, a play could only have one actor talking with the chorus. With two actors, characters could talk to each other, creating conflict and more exciting drama.

Aeschylus also created the trilogy, where three plays told one long story. His most famous trilogy is the Oresteia, which tells the story of King Agamemnon and his family. His plays often dealt with themes of justice and religion.

Sophocles: Master of Storytelling

Sophocles was a very talented playwright who won many competitions, even beating Aeschylus. His biggest innovation was adding a third actor. This allowed for even more complex stories and character relationships.

He also increased the size of the chorus and began using painted scenery to make the stage look more realistic. In Sophocles' plays, the chorus became less involved in telling the story. Instead, the plays focused more on the characters and their personal struggles. His most famous play is Oedipus Rex, a story about a king who discovers a terrible secret about his past.

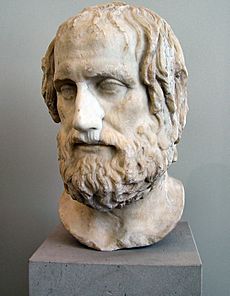

Euripides: A Focus on Realism

Euripides was known for creating very realistic and emotional characters. His heroes were not always perfect or brave. They were often troubled people with real-life problems and feelings, which made them easy for the audience to relate to.

He was also famous for his strong female characters, like Medea and Andromache. Euripides often used a special trick called the deus ex machina (which means "god from the machine"). At the end of a play, a god would suddenly appear to solve a problem that seemed impossible.

How a Greek Tragedy Was Structured

Greek tragedies followed a clear and predictable structure.

- Prologue: The play usually began with a prologue. One or two characters would come on stage to explain the background of the story.

- Parodos: After the prologue, the chorus would enter the stage, singing and dancing.

- Episodes: The main part of the play was made up of several episodes. In these scenes, the actors would interact with each other and the chorus, moving the story forward.

- Stasimon: Between each episode, the chorus would perform a song and dance called a stasimon. These songs commented on the events of the play and the themes of the story.

- Exodus: The play ended with the exodus. This was the final scene, where the chorus would exit the stage, singing a final song that wrapped up the story.

A Big Event for the Whole City

Attending a tragedy in ancient Greece was not like going to the movies today. It was a major community event and a religious ritual. The plays were performed in huge outdoor theaters that could hold thousands of people. The theatre of Dionysus in Athens, for example, could seat around 17,000 spectators.

The theater was built in a semicircle on a hillside. The audience sat in the theatron, or "seeing place." Below them was a circular area called the orchestra, or "dancing place," where the chorus performed. In the center of the orchestra was an altar for the god Dionysus.

The actors performed on a raised platform called the proskenion. Behind them was a building called the skene, which served as a backdrop. It usually looked like a palace or a temple and had doors for actors to enter and exit.

Plays were performed during the Dionysia, a big festival held every March. For three days, the city would watch plays from sunrise to sunset. It was a competition, and at the end of the festival, a jury would vote for the best playwright, actor, and chorus. The winners were celebrated as heroes. The city of Athens even helped poorer citizens pay for tickets so that everyone could attend.

Famous Surviving Plays

Even though hundreds of tragedies were written, only 32 have survived in full. Here are some of the most famous ones.

Aeschylus

- The Persians: A play about the Persian defeat at the Battle of Salamis.

- Seven Against Thebes: A story about the two sons of Oedipus fighting for control of a city.

- The Oresteia: A trilogy of plays about the murder of King Agamemnon and its aftermath.

Sophocles

- Ajax: A tragedy about a proud warrior.

- Antigone: A play about a young woman who defies the king's orders to honor her brother.

- Oedipus Rex: The famous story of a king who unknowingly fulfills a terrible prophecy.

Euripides

- Medea: The story of a woman who seeks revenge on her husband.

- The Trojan Women: A powerful play about the suffering of the women of Troy after their city is destroyed.

- The Bacchae: A tragedy about what happens when a king disrespects the god Dionysus.

Ideas About Greek Tragedy

Mimesis and Catharsis

Aristotle wrote the first big study of tragedy, called the Poetics. He used two main ideas to explain what tragedy does: mimesis (meaning "imitation") and catharsis (meaning "cleansing").

He wrote: "Tragedy is, therefore, an imitation (mimēsis) of a noble and complete action [...] which through compassion and fear produces purification of the passions."

- Mimēsis means that tragedy imitates human actions and life.

- Catharsis means a kind of emotional cleansing for the audience.

What exactly "emotional cleansing" means has been debated by scholars for a long time. Some think it means that the strong feelings of pity and fear we feel during a tragedy are transformed into something enjoyable and helpful. It's like an "education for the emotions," teaching us what to feel pity or fear about.

The Three Unities

Aristotle also talked about three "unities" for plays:

- Unity of action: A play should have only one main story, with few or no side stories.

- Unity of place: A play should happen in only one physical location. The stage shouldn't try to show many different places.

- Unity of time: The events in a play should happen within a short period, usually no more than 24 hours.

Aristotle believed a play needed to be complete, with a clear beginning, middle, and end. He also said that tragedies should be shorter than epic poems, ideally taking place within "one revolution of the sun" (one day). These unities were important in theater for many centuries, even though some famous writers like Shakespeare didn't always follow them.

Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche's Ideas

Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosopher from the late 1800s, pointed out a contrast in tragedy.

- The Dionysian part is about strong passion and emotions that take over a character.

- The Apollonian part is about the clear, beautiful images and structure of the play.

Nietzsche believed that ancient Greek culture had a conflict between these two ideas. The Apollonian was about visual arts (like sculptures), and the Dionysian was about music and emotion. He said that these two different forces worked together, often clashing, until they finally combined in Attic Tragedy. He saw Greek tragedy as a mix of both Dionysian passion and Apollonian order.

Greek Tragedy as a Big Event

Greek tragedy was more than just a show; it was a big community event for the polis (city-state). It happened in a special, sacred place, with an altar to the god Dionysus in the middle of the theater.

Imagine being a spectator in a Greek theater around the 5th century BC:

- You would sit in the theatron, a curved area of seats shaped like a horseshoe.

- Below you, in the best spot, was the throne for the priest of Dionysus, who oversaw the performance.

- The theater in Athens, at the theatre of Dionysus, was huge! It could hold about 17,000 people.

- In front of you was a flat, circular area called the orchestra, which means "dancing place." An altar stood in its center. The chorus would dance and sing here.

- On the sides of the seating area were the parodoi, paths used by both the audience and the actors/chorus to enter and exit.

- Behind the orchestra was the skene (scene building). This building usually looked like the front of a house, palace, or temple.

- The skene usually had three doors for actors to enter and exit.

- Right in front of the skene was a raised platform called the proskenion or logeion, where much of the acting happened.

The theater was a place where ideas and problems from Athens's democratic, political, and cultural life were discussed. Tragedies often used Greek myths as a way to talk about the big issues facing Athenian society at the time. For example, Aeschylus's The Persians was performed in 472 BC, just eight years after the Battle of Salamis, when the war with Persia was still going on. The play allowed Athenians to see the war from the Persian side and feel sympathy for them.

Other tragedies, especially those by Euripides, also brought the past into the present. They included ideas from Athenian politics and society of the 5th century BC. For example, Euripides's Orestes talks about political groups, which was very relevant to Athens in 408 BC.

Tragedy performances happened in Athens during the Great Dionysia, a festival honoring Dionysus in March. The government organized it, and three wealthy citizens were chosen to pay for the plays. This was a common practice in Athenian democracy, where rich citizens funded public services.

During the Dionysia, there was a contest between three playwrights. Each playwright had to present a tetralogy (a group of four plays: three tragedies and one satyr play). Each tetralogy was performed in one day, so the tragedies lasted three days. The fourth day was for comedies. At the end, a jury of ten citizens chose the best chorus, actor, and author. The winning author, actor, and chorus were chosen partly by chance and partly by votes.

The Greeks loved tragedy so much that people said Athens spent more money on theater than on its navy! When the cost became an issue, an admission fee was introduced, along with a special fund called the theorikon to help people pay for tickets.

The Tragedies We Still Have

Out of many tragedies written, only 32 full plays by three authors—Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—have survived completely. We know of more than 300 others from small pieces (fragments).

Aeschylus

We know of 79 titles of Aeschylus's works. Seven of his plays have survived, including the only complete trilogy from ancient times, the Oresteia:

- The Persians (472 BC)

- Seven Against Thebes (467 BC)

- Suppliants (around 463 BC)

- The trilogy Oresteia (458 BC), which includes:

- Prometheus Bound (date uncertain, some scholars question if it's truly by Aeschylus)

Sophocles

Sophocles wrote about 123 plays, but only seven remain complete:

- Ajax (around 445 BC)

- Antigone (442 BC)

- Women of Trachis (date unknown)

- Oedipus Rex (around 430 BC)

- Electra (date unknown)

- Philoctetes (409 BC)

- Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC)

We also have a large part of his satyr play Trackers, found on a papyrus.

Euripides

Euripides wrote many plays, and eighteen tragedies and one complete satyr play, Cyclops, have survived:

- Alcestis (438 BC)

- Medea (431 BC)

- Heracleidae (around 430 BC)

- Hippolytus (428 BC)

- The Trojan Women (415 BC)

- Andromache (date unknown)

- Hecuba (423 BC)

- Suppliants (414 BC)

- Ion

- Iphigenia in Tauris

- Electra

- Helen (412 BC)

- Heracles

- The Phoenician Women (around 408 BC)

- Orestes (408 BC)

- Iphigenia in Aulis (410 BC)

- The Bacchae (406 BC)

- Cyclops (a satyr play)

- Rhesus (possibly not by Euripides)

How Actors Connect with the Audience

The Audience's Role

In Greek tragedy, the audience was meant to feel like they were part of the play. They were supposed to get lost in the story. Sometimes, silent actors would sit with the audience to make it feel like the audience was part of the story.

The Chorus and Citizens

The chorus in tragedies often represented a specific group of people, like old men or young boys from a certain city. For example, in Aeschylus's Seven against Thebes, a female chorus is criticized for making citizens feel bad. This shows that the chorus was often seen as representing the citizens. Male choruses were sometimes named after their groups, like "Argive boys" or "jury-service-loving old men." This showed their role in the community.

Greek Tragedy as a Performance

It can be tricky to understand Greek tragedy as a "drama" in the way we think of plays today. Early Greek tragedies were mostly based on song and spoken words, not written scripts. This means they were very much about the performance.

Many scholars believe that Greek tragedy was "performative" by nature. They were often musical and sung, and they came from a strong tradition of oral storytelling. The experience of tragedy really needed a live performance; it wasn't just something to read like a book. Some even call it "pre-drama" because it doesn't quite fit our modern idea of drama that came later, like during the Renaissance.

As plays developed and more dialogue was added, the chorus sang less and less. This shows how Greek tragedy changed to include more spoken interactions between characters.

Deus Ex Machina: A Special Trick

The Deus Ex Machina is a special technique used in plays. It means "god from the machine." This is when a problem in the play is suddenly solved by an unexpected character, often a god, who appears and brings the story to an end.

An example is in Euripides's play, Hippolytus. In this play, Hippolytus is cursed to die by his father, Theseus. This happens because the goddess Aphrodite hates Hippolytus. He is completely devoted to another goddess, Artemis (who represents purity), and he rejects Aphrodite (who represents love and desire).

The play shows how a god's intervention starts the main theme of revenge, which leads to the downfall of a royal family. At the end of the play, Artemis appears to tell King Theseus that he wrongly cursed his son. Without this divine intervention, Theseus would not have realized his mistake, and the audience might not have understood the deeper truths of the story. This technique was very important in Greek tragedy for showing big ideas.

Aeschylus: Connecting with Characters

In many of Aeschylus's plays, you can really connect with the characters. For example, in Prometheus Bound, Prometheus is a Titan god. He stole fire from the gods and gave it to humans, also teaching them arts and knowledge. This made the gods angry.

In this tragedy, Prometheus is punished by Zeus not just for giving fire to humans, but also because he thought humans would praise him as a hero and see Zeus as a cruel ruler. Aeschylus's play helps the audience connect with Prometheus because he acts not for selfish reasons, but is willing to suffer for the good of humanity.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tragedia griega para niños ```

In Spanish: Tragedia griega para niños ```

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |