Jean-François Lyotard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-François Lyotard

|

|

|---|---|

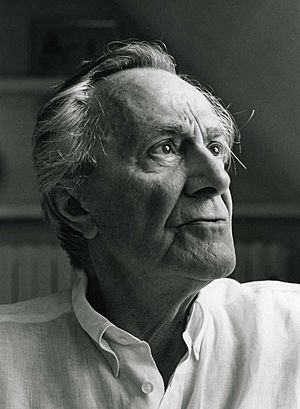

Jean-François Lyotard.

Photo by Bracha L. Ettinger, 1995. |

|

| Born | 10 August 1924 Versailles, France

|

| Died | 21 April 1998 (aged 73) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Education | University of Paris (B.A., M.A.) University of Paris X (DrE, 1971) |

| Spouse(s) | Dolores Djidzek |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Phenomenology (early) Post-Marxism (late) Postmodernism (late) |

| Institutions | Lycée of Constantine (1950–52) Collège Henri-IV de La Flèche (1959–66) University of Paris (1959–66) University of Paris X (1967–72) Centre national de la recherche scientifique (1968–70) University of Paris VIII (1972–87) University of California, Irvine (1987–94) Emory University (1994–98) Johns Hopkins University University of California, San Diego University of California, Berkeley University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Collège International de Philosophie The European Graduate School |

|

Main interests

|

The Sublime, Judaism, sociology |

|

Notable ideas

|

The "postmodern condition" Collapse of the "grand narrative", libidinal economy |

|

Influenced

|

|

Jean-François Lyotard (born August 10, 1924 – died April 21, 1998) was a French philosopher, sociologist, and literary theorist. He is famous for his ideas about postmodernism and how it affects the human condition. Lyotard wrote many books and articles. He also led the International College of Philosophy.

Contents

Jean-François Lyotard's Life

Early Life and Education

Jean-François Lyotard was born in Vincennes, France, on August 10, 1924. His father, Jean-Pierre Lyotard, was a sales representative. His mother was Madeleine Cavalli. As a child, Lyotard dreamed of being an artist, a historian, or a writer. He even tried writing a novel at age 15, but it wasn't successful.

After World War II, Lyotard studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. He wrote a thesis in 1947 about "Indifference as an Ethical Concept." This paper looked at ideas of detachment in Zen Buddhism, Stoicism, and other philosophies. He taught philosophy in Constantine, Algeria, and later in France. In 1971, he earned his doctorate with a work called Discours, figure. Lyotard was married twice and had three children.

Political Involvement

In 1954, Lyotard joined a French political group called Socialisme ou Barbarie (Socialism or Barbarism). This group questioned the ideas of Karl Marx and how power worked in the Soviet Union. Lyotard wrote many essays about the situation in Algeria, supporting its fight for independence from France. He hoped for a social revolution there.

He later left this group and another one called Pouvoir Ouvrier (Worker Power). Although he was active in the May 1968 protests in France, he started to move away from strict Marxist ideas. He felt that Marxism was too rigid and focused too much on industrial production.

Academic Career and Teaching

Lyotard taught philosophy in Algeria from 1950 to 1952. He then returned to France to teach at a military academy. In 1954, he published a book called La phénoménologie (Phenomenology). He also wrote for the journal Socialisme ou Barbarie.

From 1959, Lyotard taught at the Sorbonne in Paris. He later moved to the new campus of Nanterre in 1966. In 1970, he joined the Philosophy department at the University of Vincennes, which became the University of Paris VIII. He taught there until 1987. Lyotard also taught as a visiting professor at many universities around the world. These included Johns Hopkins University and the University of California, Irvine in the U.S. He also taught at Emory University before his death.

Lyotard's Key Ideas

Lyotard's work often challenged ideas that claim to be true for everyone. He was critical of many "universal" claims from the Enlightenment. He wanted to show how these big ideas might not be as solid as they seem.

The Postmodern Condition

One of Lyotard's most famous books is The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979). In this book, he talks about the "postmodern condition." He suggests that after World War II, people became more doubtful of "metanarratives." These are big, overarching stories or theories that try to explain everything. Examples include the idea that history always progresses, or that science can know everything.

Lyotard argued that we no longer fully believe these big stories can explain everything. Instead, he said we are more aware of differences and diverse viewpoints. Because of this, postmodern times are full of "micronarratives," which are smaller, more specific stories. He connected this idea to Ludwig Wittgenstein's concept of "language-games."

Language-Games and Justice

Lyotard used the idea of "language-games" to describe how different groups create meaning and rules for communication. He said that there are many ways of understanding the world, and these ways don't always fit together. For example, the way scientists talk about truth might be different from how artists talk about beauty.

He argued that in postmodernism, justice is still important. Injustice happens when you try to apply the rules of one "language-game" to another. For example, if you judge a work of art using only scientific rules, that might be unfair. Lyotard called a situation where a conflict cannot be solved fairly because the rules of judgment are different a "differend." He said that understanding both sides is the first step to finding a solution.

The Sublime in Art

Lyotard wrote a lot about art and beauty. He was a big supporter of modernist art. He saw postmodernism not just as a time period, but as a way of thinking that has always existed. He liked art that was surprising and challenging. He felt this kind of art showed the limits of our understanding.

He explored the idea of the "sublime." This is a feeling of mixed pleasure and anxiety you get when you see something huge and powerful, like a giant mountain. It makes you feel small but also amazed. Lyotard was especially interested in Immanuel Kant's explanation of the sublime. Kant said that when we experience the sublime, our mind struggles to fully grasp something that is too big or too powerful. This struggle shows us the limits of our reason and imagination. For Lyotard, this moment of struggle, where our usual ways of thinking break down, is important. It shows us that not everything can be neatly understood or put into simple categories.

Libidinal Economy

In his book Libidinal Economy, Lyotard looked at Karl Marx's ideas about society. He suggested that sometimes people might find pleasure in things that seem difficult or oppressive. He used the term "libidinal energy," which comes from the idea of libido in psychology, meaning deep desires. Lyotard argued that this energy can challenge fixed structures in society. This book was one of his first major criticisms of Marxist views.

The Inhuman

In his 1988 book, The Inhuman, Lyotard explored ideas from other philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Martin Heidegger. He also looked at the works of artists like Paul Cézanne. He discussed time, memory, and the link between art and politics. Lyotard questioned traditional ideas of humanism, which often assume that being "humane" is something everyone is born with but only gets through education. He asked if humanity is truly inherent if it needs to be taught.

He used a science fiction thought experiment. He imagined a future 4.5 billion years from now, when the sun explodes. If humans had to live off Earth, what would "humanity" even mean? Lyotard thought that modern technology could be dehumanizing, but also that it could open up new possibilities for what it means to be human.

Les Immatériaux Exhibition

In 1985, Lyotard helped organize a large art exhibition in Paris called Les Immatériaux. This exhibition explored how information and technology were changing art and society. It looked at the future of art in a world that was becoming more connected.

Later Life and Legacy

Towards the end of his life, Lyotard worked on books about the French writer André Malraux and a study on the philosophy of time. These works were published after his death. He also wrote essays about the artist Bracha L. Ettinger.

Lyotard often revisited his ideas about postmodernism in essays like The Postmodern Explained to Children. In 1998, he died suddenly from leukemia. He is buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Criticism of Lyotard's Work

Lyotard's ideas have been discussed and debated by many other philosophers.

Some critics, like Jacques Derrida, argued that Lyotard's focus on differences between "language-games" might make categories seem too fixed. They felt that his ideas didn't allow enough for new ways of thinking or for groups to change.

Others, like Manfred Frank, criticized Lyotard for focusing on division instead of agreement. They argued that if everything is just different "language-games," it might be hard to find common ground or solve problems fairly. They felt that Lyotard's ideas could make it harder to achieve justice.

From a different viewpoint, some, like Gilles Deleuze, felt that Lyotard's later work became too negative. They thought that his ideas about the "differend" and the "sublime" focused too much on things that cannot be understood or captured, leading to a sense of pessimism.

Despite these criticisms, Lyotard's work continues to be very important. His ideas are still studied in politics, philosophy, sociology, literature, art, and cultural studies.

Selected Publications

- Phenomenology. Trans. Brian Beakley. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991 [La Phénoménologie. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1954].

- Discourse, Figure. Trans. Antony Hudek and Mary Lydon. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011 [Discours, figure. Paris: Klincksieck, 1971].

- Libidinal Economy. Trans. Iain Hamilton Grant. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993 [Économie libidinale. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1974].

- Just Gaming. Trans. Wlad Godzich. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985 [Au juste: Conversations. Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1979].

- The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984 [La Condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1979].

- The Differend: Phrases in Dispute. Trans. Georges Van Den Abbeele. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988 [Le Différend. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1983].

- The Postmodern Explained: Correspondence, 1982–1985. Ed. Julian Pefanis and Morgan Thomas. Trans. Don Barry. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993 [Le Postmoderne expliqué aux enfants: Correspondance, 1982–1985. Paris: Galilée, 1986].

- The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991 [L’Inhumain: Causeries sur le temps. Paris: Galilée, 1988].

- Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime: Kant’s Critique of Judgment, §§ 23–29. Trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994 [Leçons sur l’"Analytique du sublime": Kant, "Critique de la faculté de juger," paragraphes 23–29. Paris: Galilée, 1991].

- Postmodern Fables. Trans. Georges Van Den Abbeele. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997 [Moralités postmodernes. Paris: Galilée, 1993].

- Signed, Malraux. Trans. Robert Harvey. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999 [Signé Malraux. Paris: B. Grasset, 1996].

- The Confession of Augustine. Trans. Richard Beardsworth. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000 [La Confession d’Augustin. Paris: Galilée, 1998].

See also

In Spanish: Jean-François Lyotard para niños

In Spanish: Jean-François Lyotard para niños

- Aestheticism

- Spatial turn

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |