Land Ordinance of 1785 facts for kids

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was an important law passed by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. This law created a clear system for people to buy land in the new western territories. Back then, the government couldn't collect taxes directly, so selling land was a key way to make money.

This Ordinance also set up a special way to measure and divide land. This system eventually covered more than three-quarters of the United States. It helped organize how the country would grow westward.

Before this, the Land Ordinance of 1784, written by Thomas Jefferson, suggested dividing the land west of the Appalachian Mountains into new states. But it didn't explain how the land would be sold or governed. The 1785 Ordinance fixed this by providing a way to sell and settle the land. Later, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 dealt with how these new territories would be governed and become states.

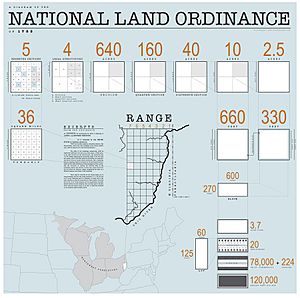

The 1785 Ordinance created the foundation for how land was managed until the Homestead Act of 1862. It set up the Public Land Survey System. The first person in charge of surveying was Thomas Hutchins. After he passed away, the Surveyor General took over. Land was divided into square townships, each about 6 miles (9.7 km) on a side. Each township was then split into thirty-six sections, each about 1 square mile (2.6 km²) or 640 acres (259 ha). These sections could then be sold to settlers and land buyers.

This law was also important because it helped fund public education. Section 16 in every township was set aside to support public schools. Even today, many schools are still located in section sixteen of their townships. In some later states, section 36 was also used for schools.

The starting point for the 1785 survey was where Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (now West Virginia) meet. This spot is on the north side of the Ohio River near East Liverpool, Ohio. You can find a historical marker there today.

Contents

How the Ordinance Was Created

The Confederation Congress formed a committee to create this important land law. The committee members included:

- Thomas Jefferson from Virginia

- Hugh Williamson from North Carolina

- David Howell from Rhode Island

- Elbridge Gerry from Massachusetts

- Jacob Read from South Carolina

In 1784, this group suggested a plan to divide western lands into "hundreds" of ten miles square. These would then be broken down into smaller "lots" of one mile square. After much discussion and changes, the final plan was presented to Congress in April 1785. It suggested dividing the land into "townships" that were seven miles square. These townships would then be marked into "sections" of one mile square, or 640 acres. This was the first time the words "township" and "section" were used in this way.

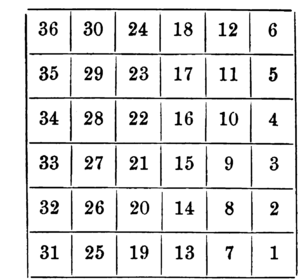

On May 3, 1785, William Grayson suggested changing the size of townships from seven miles square to six miles square. This change was approved, and the Ordinance passed on May 20, 1785. The sections within each township were to be numbered starting from 1 in the southeast corner and going north, ending with 36 in the northwest corner. Thomas Hutchins was in charge of these surveys. This numbering system was used for the Seven Ranges and other early land sales in Ohio.

Later, in 1796, a new law changed how sections were numbered. They would start with number one in the northeast corner and then go west and east alternately across the township until all thirty-six sections were numbered. This new system was used for almost all surveys after that.

Support for Public Education

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was very important for public schooling. It set aside school lands by granting Section 16 (one square mile) of every township for public education. The law stated: "There shall be reserved the Lot No. 16, of every township, for the maintenance of public schools within said township."

Section 16 was usually near the center of the township. In many western states, Section 36 was also later added as a "school section." While states and counties sometimes changed these rules, the main idea was to give local schools a steady income and make sure schoolhouses were easy for all children to reach.

These "School Lands" were part of the Ohio Lands, which were land grants from the U.S. government for public schools. By 1920, over 73 million acres of public land had been given to states to support public schooling. The 1785 Ordinance also set aside land for higher education, known as the College Lands.

How Townships Were Laid Out

Each western township was designed as a square, six miles on each side, containing thirty-six square miles of land. This area was then divided into thirty-six smaller lots, each one square mile. This precise planning was done by surveyors.

Each township had special areas set aside for public education and other government uses. Five of the thirty-six lots were reserved for public purposes. The lots were numbered on each township's survey. Lot number 16, located near the center of the township, was specifically for public education. As the Ordinance stated, "There shall be reserved the lot No. 16, of every township, for the maintenance of public schools within the said township."

Other sections, like numbers 8, 11, 26, and 29, were kept by the federal government for future sale. The idea was that these lands would become more valuable as the areas around them developed. The Ordinance also tried to reserve three townships near Lake Erie for Canadian and Nova Scotian refugees. However, this area was owned by Connecticut, so the refugees had to wait for the Refugee Tract to be established later.

Why This Ordinance Was Important

Many historians believe the Land Ordinance of 1785 was shaped by the experiences of the early American colonies. The people who created this law tried to use the best ideas from different states. The way townships were surveyed and planned in the 1785 Ordinance was a mix of different colonial ideas.

Two main land systems existed in colonial times: the New England system and the Southern system. The New England system focused on community development and careful planning. The Southern system was more about individuals claiming land on their own.

Even though the committee that wrote the Ordinance had more members from the South, they chose to use the New England survey system. The highly planned western townships, with land set aside for public education, were strongly influenced by New England settlements. In colonial New England, towns often had dedicated public spaces for schools and churches. For example, a 1751 charter for Marlboro, Vermont, set aside land for a minister and for a school. By the time the 1785 Ordinance was passed, New England states had been using land grants to support schools for over a century. The idea of dedicating "Lot Number 16" for public education came from this New England experience.

The use of surveyors to precisely map out new townships also came from the New England system. This helped create clear property lines and a reliable land ownership system. This was important because it made people feel more secure about buying land, which helped the government raise money. The organized settlements also allowed the government to keep some well-defined plots of land for future development. These reserved lands would become more valuable as the surrounding areas grew.

While the New England system was the main influence, the Southern land system also played a role. The Southern system focused on individual pioneers claiming undeveloped land. This often led to large plantations and less organized settlements. The committee's decision to use a more organized system, rather than "indiscriminate location," might have been an attempt to prevent the spread of a plantation economy that relied on enslaved labor.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 created the land system, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 decided how the townships would be governed. The Northwest Ordinance also encouraged religion and education, similar to New England settlements. However, it also had Southern influences, allowing local communities more freedom to govern themselves once the land was set aside. This meant that while the Ordinances created a national framework for schools, the actual development and management of public schools became the responsibility of local townships and states.

Why It Was Created

Setting aside central land in each township helped the federal government and the people. Instead of giving money to new states for education, dedicating land gave townships the means to build schools without direct money transfers. This was a smart and necessary way to achieve the goal in a time before the U.S. Constitution was written.

Besides raising money for a government that was struggling financially, the westward expansion also helped spread democratic ideas. Thomas Jefferson tried to include a rule in the Ordinance that would have outlawed slavery in the new states after 1800, but he couldn't get enough votes. However, he did succeed in getting public funding for education by setting aside land for schools in the 1785 Ordinance. Public education was an idea already strong in New England. People there believed that public education could help unite the new nation and spread democratic values.

The organized western settlements, with their local governments and central square for public education, were a way to encourage civic duty and participation in democracy. The hope was that the unique planning of each township, with a public school at its center, combined with the responsibility of citizens to govern their township, teach in and build schools, and maintain order, would help instill the democratic ideals crucial for the nation's success.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |