History of Harlem facts for kids

Harlem, a famous neighborhood in New York City, has a long and interesting history. It started in the 1600s as a Dutch settlement. Over time, it grew from a farming village into a busy town. It became known as a place for wealthy people to visit and later, a home for many people who traveled to work in the city. Most importantly, Harlem became a very important center for African-American culture and history.

Contents

- Early Days: From Dutch Village to American Town (1637–1866)

- Growth and Change: From Post-War Boom to Diverse Communities (1866–1920)

- The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1921–1929)

- Challenges and Activism (1930–1945)

- Civil Rights and Community Efforts (1946–1969)

- Rebuilding and Renewal (1970–1989)

- New Beginnings and Growth (1990s)

- Harlem Today (2000–Present)

- Images for kids

Early Days: From Dutch Village to American Town (1637–1866)

Before Europeans arrived, the area we now call Harlem was home to Native American tribes, like the Manhattans and Lenape. They farmed the flatlands and lived a semi-nomadic life. The first European settlers, the de Forest family, arrived in 1637 from the Netherlands. In 1639, Jochem Pietersen Kuyter started a farm called Zegendaal, or Blessed Valley, along the Harlem River.

The early European settlers sometimes had to leave and go to New Amsterdam (now lower Manhattan) when there were conflicts with the Native Americans. The Dutch officially named the settlement Nieuw Haarlem in 1660, after a city in the Netherlands. Peter Stuyvesant, a famous Dutch leader, helped establish it. A path used by Native Americans was later improved and became the Boston Post Road.

In 1664, the English took control of the colony. The English governor, Richard Nicolls, set a border for the village of Nieuw Haarlem, which later became just "Harlem." The British tried to rename it "Lancaster," but the old name stuck. The Dutch briefly took control again in 1673. Harlem grew slowly, becoming a popular resort for wealthy New Yorkers in the mid-1700s. The Morris–Jumel Mansion is one of the few buildings left from this time.

Harlem played a key role in the American Revolution. George Washington set up defenses in Harlem to fight the British, who were based in lower Manhattan. This allowed him to control important land routes and river traffic.

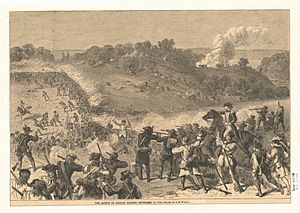

On September 16, 1776, the Battle of Harlem Heights took place. American troops, though outnumbered, managed to outsmart the British and force them to retreat. This was an important early victory for George Washington. However, later that year, the British burned Harlem to the ground.

Rebuilding Harlem took many years. It remained mostly a rural area through the early 1800s, with large farms and estates. Even when New York City's street grid system was extended to Harlem in 1811, people didn't expect it to become a busy city area for a long time.

Despite being undeveloped, Harlem was not poor. It was known for "elegant living" for much of the 1800s. Wealthy farmers, sometimes called "patroons," owned large country estates, especially overlooking the Hudson River. Travel to New York City was by steamboat or stagecoach.

The New York and Harlem Railroad was built starting in 1831 to connect Harlem better with the city. This railroad helped Harlem grow. A wealthy lawyer named Charles Henry Hall saw the potential and helped build streets, gas lines, and sewers. Piers were also built, making Harlem an industrial area that served New York City. This rapid growth made some people rich, and many politicians lived in Harlem. The village also had poorer residents, including black people, who came north for factory jobs or cheaper housing.

Between 1850 and 1870, many large estates, like Hamilton Grange (home of Alexander Hamilton), were sold off. Some land was even taken over by Irish squatters, which made property values drop.

Growth and Change: From Post-War Boom to Diverse Communities (1866–1920)

After the American Civil War, Harlem experienced a big economic boom starting in 1868. Many people moved north, including poor Jewish and Italian immigrants. Factories, homes, churches, and shops were built very quickly. However, a financial crisis in 1873 caused property values in Harlem to drop sharply. This led New York City to take over the community.

Harlem soon recovered, and new homes were built rapidly, especially after elevated trains reached Harlem in 1880. People expected the new subway line to make travel to lower Manhattan even easier. Developers rushed to build before new housing rules came into effect in 1901.

Early developers had big plans for Harlem. Polo was played at the original Polo Grounds, which later became home to the New York Giants baseball team. The Harlem Opera House opened in 1889. By 1893, large apartment buildings were common to house the growing population. A magazine even wrote that Harlem would soon be a center of "fashion, wealth, culture, and intelligence."

However, a building boom and subway delays caused real estate prices to fall again. This attracted more Jewish and Italian immigrants to Harlem. By 1915, nearly 200,000 Jewish people lived in Harlem. Some existing landowners tried to stop Jewish people from moving in, with signs even saying "No Jews and no dogs." Italians also began arriving, with 150,000 in Harlem by 1900. Both groups settled especially in East Harlem.

The Jewish community in Harlem supported the City College of New York, which moved there in 1907. Many famous graduates from the school were Jewish during this time. Some crime groups also started in East Harlem and grew. However, Harlem also became a major center for entertainment, with 125th Street being famous for musical theater and vaudeville.

The Jewish population in Harlem was temporary, and most had left by 1930. As they moved out, their apartments in East Harlem were filled by Puerto Ricans, who began arriving in large numbers around 1913. The Italian community in Harlem lasted longer, with some traces remaining even today around Pleasant Avenue.

Black Population Increases in Harlem

Black residents have lived in Harlem since the 1630s. By the late 1800s, many lived around 125th Street. A large movement of black people into Harlem began in 1904. This was due to another real estate downturn, difficult living conditions for black people in other parts of the city, and the efforts of black real estate leaders like Phillip Payton, Jr.. When landlords couldn't find white renters, Payton helped black families move in. His company, the Afro-American Realty Company, helped many black people move from older neighborhoods like the Tenderloin and San Juan Hill.

This move to northern Manhattan was also influenced by fears of anti-black riots that had happened in other parts of the city. Also, some buildings where black people lived were torn down to build the original Penn Station.

In 1907, black churches also started moving to Harlem. Many built grand new buildings or bought churches from white congregations that had left the neighborhood. Only Catholic churches kept their buildings, with white priests serving parishes that still had many white members until the 1930s.

The "Great Migration" of black people to northern cities in the early 1900s was driven by a desire to escape unfair laws and violence in the South. They also sought better jobs and education for their children. During World War I, industries needed more workers, and many black laborers moved north to fill these jobs.

Many settled in Harlem. In 1910, about 10% of Central Harlem's population was black. By 1920, it was over 32%, and by 1930, more than 70% of Central Harlem residents were black. This growth was mainly due to people moving from southern U.S. states like Virginia and Georgia, as well as immigrants from the West Indies. As black people moved in, white residents moved out. Between 1920 and 1930, over 118,000 white people left, and over 87,000 black people arrived.

Between 1907 and 1915, some white residents tried to stop the changes in Harlem, especially as the black population grew west of Lenox Avenue, which was an unofficial dividing line. Some made agreements not to sell or rent to black people. Others tried to buy properties and evict black tenants, but the Afro-American Realty Company fought back by buying other properties and evicting white tenants. Some even tried to convince banks not to give loans to black buyers, but these efforts soon stopped.

Soon after black people moved into Harlem, it became known as a center for the "Negro protest movement." The NAACP became active in Harlem in 1910, and Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association started in 1916. The NAACP chapter in Harlem quickly became the largest in the country. Activist A. Philip Randolph lived in Harlem and published a magazine called The Messenger. He also organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Many other important black leaders and writers, like W. E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, lived and worked in Harlem during the 1920s.

Italian Harlem's Story

People from Southern Italy and Sicily, along with some from Northern Italy, soon became the main group in East Harlem. They settled especially east of Lexington Avenue between 96th and 116th Streets, and east of Madison Avenue between 116th and 125th Streets. Each street often had people from different parts of Italy. This area became known as "Italian Harlem" and was the first part of Manhattan to be called "Little Italy." The first Italians arrived in East Harlem in 1878.

Some organized crime groups were active in Italian Harlem. It was the starting place for the Genovese crime family, one of the main crime families in New York City.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, Italian Harlem was represented in Congress by Fiorello La Guardia, who later became mayor. The Italian neighborhood reached its largest size in the 1930s, with over 100,000 Italian-Americans living in its busy apartment buildings. By 1930, 81% of Italian Harlem's population was first- or second-generation Italian Americans.

Although some Italian families remained in areas like Pleasant Avenue into the 1970s, most of the Italian population has now left. Today, only a small number of older residents remain, mostly around Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church.

However, some parts of the old Italian neighborhood still exist. The annual Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the "Dancing of the Giglio" is still celebrated there every year in August. Italian businesses like Rao's restaurant, which started in 1896, and the original Patsy's Pizzeria (opened in 1933) are still open.

The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1921–1929)

Around the end of World War I, Harlem became famous for the "New Negro" movement. This led to the amazing artistic period known as the Harlem Renaissance, which included poetry, novels, theater, and visual arts.

The growing population in the 1920s also supported many groups and activities. Fraternal orders like the Prince Hall Masons and the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks built lodges with auditoriums and bands. Parades with uniformed members and music were common sights on Harlem's streets during holidays and celebrations.

Churches in the neighborhood hosted many groups, including sports clubs, choirs, and social clubs. Similar activities were available at the YMCA and YWCA. Harlem's black newspapers, the New York Age and the New York Amsterdam News, reported on hundreds of small clubs' meetings and events. Speakers would draw crowds on Seventh and Lenox Avenues, some giving political speeches, like Hubert Harrison, while others sold medicines.

Harlem also offered many sporting events. Baseball teams like the Lincoln Giants played at Olympic Field. Men's and women's basketball teams played in church gyms and later at the Manhattan Casino. Boxing matches also took place. Large crowds, including many white people, came to watch black athletes compete.

In 1921, Belstrat Laundry was started in Harlem. It was the largest employer in Harlem, with over 65 workers and many horses and carriages.

It took time for black people to own many businesses in Harlem. A survey in 1929 found that white people owned and operated over 81% of the neighborhood's businesses. Beauty parlors were the most common type of black-owned business. By the late 1960s, 60% of businesses in Harlem were black-owned, and most new businesses after that were also black-owned.

Some black people found success in illegal activities, like running illegal lotteries called "numbers games." These games became very popular by 1924, making millions of dollars each year. The most successful people who ran these games were called "Kings" and "Queens." Casper Holstein, who was thought to have invented the game, was one of the wealthiest. He owned cars and apartment buildings. He and other lottery operators often gave money to charities and helped aspiring business owners and needy residents. Holstein also supported Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and helped artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Harlem quickly adapted to Prohibition, a time when alcohol was illegal. Its theaters, nightclubs, and secret clubs (called speakeasies) became major entertainment spots. Many white people came to Harlem for entertainment. Writer Langston Hughes described this period, noting that white people would fill expensive clubs like the Cotton Club, which often did not welcome black customers unless they were celebrities. He also wrote that ordinary black people did not like the increasing number of white visitors who would take the best tables in clubs.

In response to the influx of white visitors, some black residents opened "buffet flats" in their homes. These were private gatherings where people could find alcohol, music, dancing, and sometimes gambling. They were usually in residential buildings, offering more privacy from police and white visitors. You could only find them if you knew the address.

After World War I, many people from Puerto Rico and other Latin American countries moved to East Harlem, especially around 110th Street and Lexington Avenue. This area became known as "Spanish Harlem." Over time, this community grew to include all of East Harlem, as Italians moved out and Hispanic people moved in during the 1940s and 1950s.

The new Puerto Rican population shaped the neighborhood, opening small grocery stores called "bodegas" and shops selling herbs and religious items called "botánicas." By the 1930s, there was an indoor market called "La Marqueta" ("The Market"). Catholic and Protestant churches also appeared in storefronts. While "Spanish Harlem" was used since the 1930s, the name "El Barrio" ("The Neighborhood") became popular among residents later on.

This period of Harlem's history is often seen as very exciting and romantic. However, it was also a time when the neighborhood started to decline and face problems like poverty and crime. For example, "rent parties" became common. These were informal gatherings where people paid to attend, and the money helped the host pay their monthly rent. These parties, though fun, were often a necessity for survival.

Also, over a quarter of black households in Harlem took in lodgers (people who rented a room). While many were family, some brought bad habits or crime. This caused problems for families and lodgers, who often had to move frequently. Housing reformers tried to stop this "lodger evil," but it got worse before it got better. In 1940, during the Great Depression, 40% of black families in Harlem had lodgers.

The high rents and poor upkeep of housing in Harlem were not just due to racism from white landlords. By 1914, 40% of Harlem's private houses and 10% of its apartment buildings were owned by black people. Wealthier black people continued to buy land, and by 1920, a large part of the neighborhood was black-owned.

In 1928, the first effort to improve housing was made with the Paul Laurence Dunbar Houses, supported by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.. These were meant to help working people buy their own homes. But the Great Depression hit soon after, and the plan didn't work as hoped. They were followed by the Harlem River Houses in 1936, a more modest housing project. By 1964, nine large public housing projects had been built in Harlem, housing over 41,000 people.

Challenges and Activism (1930–1945)

The Great Depression caused many job losses in Harlem. The end of Prohibition in 1933 and the Harlem Riot of 1935 also scared away wealthy white people who supported Harlem's entertainment industry. White audiences almost completely disappeared after a second riot in 1943. Many Harlemites found work in the military or shipyards during World War II, but the neighborhood declined quickly after the war ended. Some middle-class black families moved to suburbs, a trend that increased after the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s reduced housing discrimination.

Harlem received few benefits from the large public works projects in New York during the 1930s. As a result, it had fewer parks and public recreation areas than other neighborhoods. Of the 255 playgrounds built in New York City by Robert Moses, only one was in Harlem.

The first efforts by black people to improve conditions in Harlem came during the Great Depression with the "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work" movement. This successful campaign aimed to force shops on 125th Street to hire black employees. Protests began in 1934 against Blumstein's Department Store, which soon agreed to hire more black staff. This success encouraged Harlem residents, and protests continued under leaders like preacher and future congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., seeking to change hiring practices at other stores.

In 1935, the first of Harlem's five riots broke out. It started because of a rumor that a boy caught stealing from a store on 125th Street had been killed by the police. By the end, 600 stores had been looted, and three men were dead. The same year, Harlemites showed interest in international events, holding rallies and signing petitions against the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. This international focus continued, including demonstrations supporting Egyptian president Nasser in 1956.

Black Harlemites began to hold elected political positions in New York in 1941, with the election of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. to the City Council. He was easily elected to Congress in 1944. However, Harlem's political influence soon weakened as Clayton Powell, Jr. spent much of his time in Washington or his vacation home.

In 1943, the second Harlem riot occurred. It was sparked by a rumor that a black soldier had been killed by a policeman. This news spread and caused widespread rioting. A large force of police and military was needed to stop the violence. Hundreds of businesses were destroyed and looted. Six people died, and 185 were injured.

Civil Rights and Community Efforts (1946–1969)

Many groups in Harlem became active in the 1960s, fighting for better schools, jobs, and housing. Some groups were peaceful, while others supported violence. By the early 1960s, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had offices on 125th Street and helped negotiate with the city, especially during times of racial tension. They pushed for civilian review boards to handle complaints about police actions, which was eventually granted. As chairman of a House committee, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. used his position to bring federal money to development projects in Harlem.

The largest public housing projects in Harlem during these years were built in East Harlem. Old buildings were torn down and replaced with city-managed properties, aiming to create safer and nicer living environments. However, community objections eventually stopped the construction of new projects.

Since the mid-1900s, the poor quality of local schools has been a major concern. In the 1960s, about 75% of Harlem students tested below their grade level in reading, and 80% were below grade level in math. In 1964, Harlem residents organized two school boycotts to highlight this problem. In central Harlem, 92% of students stayed home from school.

1960s Protests and Riots

The peaceful protest movement from the South had less impact in Harlem. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was the most respected black leader in Harlem. However, on September 20, 1958, a woman named Izola Curry attacked Dr. King at a book-signing, stabbing him with a letter opener. Police officers took King to Harlem Hospital for surgery. News reports later noted that both black and white officers and surgeons worked together to save his life, showing that "the color of their skin meant nothing."

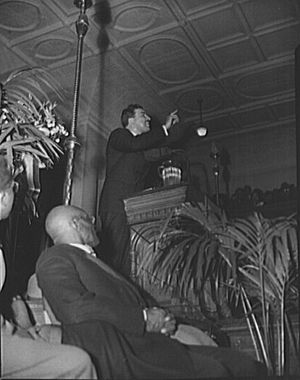

At least two dozen black nationalist groups also operated in New York, many in Harlem. The most important was the Nation of Islam, whose Temple Number Seven was led by Malcolm X from 1952–1963. Malcolm X was later assassinated in 1965. Harlem remains an important center for the Nation of Islam.

In 1963, Inspector Lloyd Sealy became the first African-American officer to command a police station in New York City, the 28th precinct in Harlem. Relations between Harlem residents and the police were tense, and civil rights activists asked the police department to hire more black officers, especially in Harlem. In 1964, there was only one black police officer for every six white officers in Harlem's three precincts.

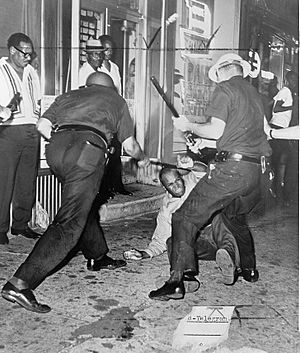

A riot occurred in the summer of 1964 after a white police lieutenant fatally shot an unarmed 15-year-old black teenager. One person died, over 100 were injured, and hundreds were arrested. There was a lot of property damage and looting. The riot also spread to Brooklyn. After the riots, the government funded a program called Project Uplift, which gave jobs to thousands of young people in Harlem during the summer of 1965.

In 1966, the Black Panthers formed a group in Harlem, encouraging strong actions for change.

In April 1968, Harlemites protested after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., similar to protests in over 100 other U.S. cities. Two people died. However, the protests in New York were less severe than in other cities. Mayor John Lindsay helped calm the situation by walking through the crowds on Lenox Avenue.

Housing Conditions

Little money was invested in private homes or businesses in Harlem between 1911 and the 1990s. However, because landlords elsewhere in the city often refused to rent to black tenants, and because the black population in New York grew a lot, rents in Harlem were often higher than in other parts of the city, even as buildings fell apart. In the late 1920s, a typical white working-class family paid $6.67 per month per room, while black families in Harlem paid $9.50 for the same space. The worse the housing and the more desperate the renter, the higher the rents could be. This continued into the 1960s.

High rents encouraged some property speculators to use a practice called "block busting." This is where they would buy one property on a block and sell or rent it to black families with a lot of publicity. Other landowners would then panic and sell their houses cheaply to the speculators. These houses could then be rented profitably to black families.

After the Harlem River Houses, America's first government-supported housing project, opened in 1937, many other large housing projects were built over the next twenty years, especially in Harlem.

After World War II, Harlem was no longer home to most of the city's black population, but it remained the cultural and political center for black New York. The community changed as middle-class black families moved to other parts of New York City (like the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn) and to the suburbs. The percentage of black people in Harlem reached its highest point in 1950, at 98.2%. After that, the number of Hispanic, Asian, and white residents increased.

The high cost of space forced people to live in crowded conditions. Harlem's population density was very high in the 1920s, with over 215,000 people per square mile. In comparison, Manhattan as a whole had a population density under 70,000 per square mile in 2000. The same reasons that allowed landlords to charge more for Harlem space also meant they spent less on maintenance. Many residential buildings in Harlem fell into disrepair. In 1960, only 51% of housing in Harlem was considered "sound," compared to 85% elsewhere in New York City.

In 1968, the New York City Buildings Department received 500 complaints daily about rats, falling plaster, lack of heat, and bad plumbing in Harlem buildings. Sometimes, tenants were also to blame, damaging properties or leaving garbage.

As buildings decayed, landlords converted many into "single room occupancies" (SROs), which were like private homeless shelters. Often, the money from these buildings wasn't enough to cover fines and taxes, or the damage was too expensive to fix, so buildings were abandoned. In the 1970s, this problem grew so much that Harlem, for the first time since before World War I, had a lower population density than the rest of Manhattan.

Between 1970 and 1980, for example, a part of central Harlem lost almost a third of its population and nearly a quarter of its housing. By 1987, 65% of Harlem's buildings were owned by New York City, and many were empty shells, used for illegal activities. The lack of good buildings and falling population reduced tax money for the city and made the neighborhood even less attractive for homes and businesses.

Poor housing contributed to social problems and health issues. However, the lack of new development also meant that many beautiful original townhouses from the 1870–1910 building boom were preserved. Harlem has many of the finest original townhouses in New York, designed by famous architects.

Rebuilding and Renewal (1970–1989)

The 1970s were a very difficult time for Harlem. Some residents left to find safer streets and better schools in the suburbs. Despite efforts like the federal government's Model Cities Program, which spent $100 million on job training, healthcare, education, and housing, Harlem did not show much improvement.

Statistics from this period show the decline. In 1968, Harlem's infant mortality rate was 37 for every 1000 live births, compared to 23.1 in the city as a whole. Eight years later, the city's rate improved to 19, but Harlem's rate increased to 42.8, more than double. Other statistics about health, housing, and education also showed rapid decline in the 1970s. So many homes were abandoned that between 1976 and 1978, central Harlem lost almost a third of its population. The neighborhood's economy was struggling; by 1971, it was estimated that 60% of the area's economic life depended on money from illegal lotteries.

The most dangerous part of Harlem was the "Bradhurst section." In 1991, the New York Times described it as having many poor, unemployed residents. Nearly two-thirds of households had low incomes. The area had a high crime rate, with garbage-filled vacant lots and abandoned buildings, creating a sense of danger.

Plans to improve Harlem often started with fixing 125th Street, which had long been the economic heart of black Harlem. In 1978, Harlem artist Franco the Great began painting over 200 storefronts on 125th Street to create a positive image of Harlem. However, by the late 1970s, only small, struggling shops remained.

There were plans for a "Harlem International Trade Center" and a related shopping complex. However, these plans needed a lot of money from the federal government, and with the election of Ronald Reagan, they were not completed.

The city did provide one large construction project, though it wasn't popular with residents at first. Starting in the 1960s, Harlemites fought against building a huge sewage treatment plant on the Hudson River in West Harlem. A compromise was reached: the plant was built with a state park, including many recreational facilities, on top. This park, called Riverbank State Park, opened in 1993.

The city began selling its many properties in Harlem to the public in 1985. The goal was to improve the community by putting properties into the hands of people who would live in and maintain them. In many cases, the city would even renovate a property before selling it below market value. However, the program faced problems, including buyers who would buy houses from the city, inflate their value, and then sell them to churches or charities who would default on the loans. This left abandoned buildings to decay further and created difficult conditions for tenants in those buildings.

New Beginnings and Growth (1990s)

After four decades of decline, Central Harlem's population reached its lowest point in the 1990 census, with 101,026 people. This was a 57% decrease from its peak in 1950. Between 1990 and 2015, the neighborhood's population grew by 16.8%. The percentage of black people decreased from 87.6% to 62%, while the percentage of white people increased from 1.5% to 10% by 2015. Hispanic people are the second largest group in Central Harlem, making up 23% of the population in 2015. White people are the fastest-growing group, with a 678% increase since 1990.

From 1987 to 1990, the city removed old trolley tracks from 125th Street, installed new water pipes and sewers, put in new sidewalks, traffic lights, and streetlights, and planted trees. Two years later, national chain stores opened branches on 125th Street for the first time. The development of the area greatly improved with the 1994 introduction of the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, which brought $300 million in development funds and $250 million in tax breaks.

Plans were made for shopping malls, movie theaters, and museums. However, these plans were almost stopped by a 1995 attack on Freddy's Fashion Mart, which killed 8 people.

Five years later, the revitalization of 125th Street continued. A Starbucks opened in 1999, partly supported by Magic Johnson. The first supermarket in Harlem in 30 years opened, along with the Harlem USA retail complex, which included the first modern movie theater in many years (2000). A new home for the Studio Museum in Harlem also opened in 2001. In the same year, former president Bill Clinton opened an office in Harlem. In 2002, a large shopping and office complex called Harlem Center was completed. Since then, there has been a lot of new construction and renovation of older buildings.

After many false starts, Harlem began to see rapid changes in the late 1990s. This was due to new government policies, including strong efforts to reduce crime and develop the shopping area on 125th Street. The number of homes in Harlem increased by 14% between 1990 and 2000, and the growth has been even faster recently. Property values in Central Harlem increased by nearly 300% during the 1990s, while the rest of New York City saw only a 12% increase. Even empty buildings in the neighborhood were selling for nearly $1,000,000 each by 2007.

Harlem Today (2000–Present)

In January 2010, The New York Times reported that in "Greater Harlem" (the area from the East River to the Hudson River, from 96th Street to 155th Street), black people stopped being the majority of the population in 1998. This change was mostly due to the fast arrival of new white and Hispanic residents. The newspaper reported that the population of the area had grown more since 2000 than in any decade since the 1940s. Housing prices in Harlem dropped more than in the rest of Manhattan during the 2008 financial crisis, but they also recovered more quickly.

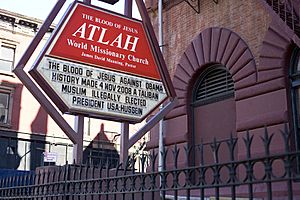

The changes in the neighborhood have caused some disagreement. James David Manning, a pastor in Harlem, has received attention for calling for a boycott of all Harlem shops, restaurants, and businesses except his own. He believes this will cause an economic downturn that will make white residents leave and lower property values so his supporters can afford them. There have also been rallies against gentrification, which is when a neighborhood changes due to wealthier people moving in.

On March 12, 2014, two buildings in East Harlem were destroyed in a gas explosion. By the mid-2010s, less than 40% of Harlem's population was Black, and the white and Asian populations were growing significantly. The COVID-19 pandemic in New York City in 2020 led to more white residents moving to Harlem from Midtown.

Images for kids

-

Marcus Garvey in 1925.

-

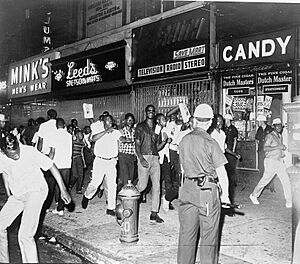

An incident at 133rd Street and Seventh Avenue during the Harlem Riot of 1964.

-

Malcolm X at a 1964 press conference.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |