Gowanus Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gowanus Canal |

|

|---|---|

| Superfund site | |

| Geography | |

| City | Brooklyn, New York City |

| County | Kings |

| State | New York |

| Coordinates | 40°40′23″N 73°59′49″W / 40.673°N 73.997°W |

| Information | |

| CERCLIS ID | NYN000206222 |

| Contaminants | PAHs, VOCs, PCBs, pesticides, metals |

| Progress | |

| Proposed | September 4, 2009 |

| Listed | April 3, 2010 |

| List of Superfund sites | |

The Gowanus Canal (once called the Gowanus Creek) is a canal in Brooklyn, New York City. It is about 1.8-mile-long (2.9 km) and is on the western part of Long Island. This canal used to be very important for moving goods by boat. But since the mid-1900s, it has been used less as other ways of shipping became popular. Today, small boats, tugs, and barges still use it sometimes.

The Gowanus Canal connects to Gowanus Bay in Upper New York Bay. It is next to neighborhoods like Red Hook, Carroll Gardens, and Gowanus. It also borders Park Slope, Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, and Sunset Park. Seven bridges cross the canal. These include bridges for Union Street, Carroll Street, Third Street, the New York City Subway's Culver Viaduct, Ninth Street, Hamilton Avenue, and the Gowanus Expressway.

The canal was created in the mid-1800s from natural wetlands and streams. By the late 1800s, many factories used the canal. They dumped a lot of pollution into it. People tried to clean the canal or make the water flow better, but it didn't work. Even though most factories stopped using the canal by the mid-1900s, the pollution stayed. By the 1990s, it was known as one of the most polluted waterways in the United States. It has many harmful germs and very little oxygen. This means it's not good for most sea creatures. However, some special tiny living things, called extremophiles, have been found there.

Even with all the pollution, the canal is close to Manhattan and nice Brooklyn neighborhoods. This has led to plans for new buildings and parks along the water. This also brought new calls for environmental cleanup. Some people worried that new buildings might make it harder to clean up the canal. In 2009, the canal was named a Superfund site. This means it needs a big cleanup. Work to clean it began in 2013.

Where the Canal Flows

The Gowanus Canal starts at Butler Street in the Boerum Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn. A old pumping station from 1911 is located near the start of the canal. The canal then flows south, between Bond Street and Nevins Street. It passes under bridges at Union Street, Carroll Street, and Third Street. The Union Street and Third Street Bridges are bascule bridges, meaning they lift up. The Carroll Street Bridge is a retractable bridge that can roll away to let ships pass.

On the west side of the canal, there is a boat launch at Second Street. Next to it is a "Sponge Park." This park helps soak up pollution from the land before it can get into the canal. At Fourth Street, a part of the canal called the Fourth Street Basin splits off to the east. The main canal then turns west. A walkway with seats is on the north side of the 4th Street Basin. It was built when a Whole Foods Market was constructed.

Near Hoyt Street, the canal turns south. Two smaller tributaries (smaller waterways) join it from the east. One is about 480-foot-long (150 m) at Seventh Street. Another is about 700-foot-long (210 m) near Sixth Street. Soon after, the canal goes under the Ninth Street Bridge. This bridge lifts straight up and opened in 1999. The New York City Subway's Culver Viaduct is a tall bridge that crosses above the Ninth Street Bridge. The Smith–Ninth Streets subway station is partly over the canal. There is also a short tributary to the east, about 185 feet (56 m) long. It connects to a Lowe's home-improvement store. A walkway leads from Lowe's to Ninth Street along this tributary and the canal. This walkway is not used much because it is hidden.

Around 14th Street on the east side, Hamilton Avenue and the Gowanus Expressway cross the canal. They connect to Lorraine Street on the west side. Two separate bridges built in 1942 carry Hamilton Avenue traffic. The Gowanus Expressway is on a tall bridge far above the canal.

The Gowanus Canal ends at Gowanus Bay, which is part of Upper New York Bay. This end is near 19th Street on the east side, or Bryant Street on the west side. From here, the canal flows north-northeast, east of Smith Street. An asphalt plant, a marine transfer station, a Home Depot, and a FedEx Shipping Center are on the canal's eastern bank.

History of the Gowanus Canal

Early Times

Mill Creek

The area around the Gowanus neighborhood used to be called Gowanus Creek. It was a natural area with creeks, marshland, and meadows. Many wild animals lived there. The Dutch government gave out the first land permits in Brooklyn between 1630 and 1664. In 1636, leaders of New Netherland bought the land around Gowanus Bay. In 1639, people traded land to build a tobacco plantation. Early settlers named the waterway "Gowanes Creek" after Gouwane. He was a chief of the local Lenape tribe called the Canarsee, who farmed along the shores.

Adam Brouwer, a soldier, built the first tide-water gristmill in New York at Gowanus. This mill used the tides to grind grain. It was the first gristmill in Brooklyn. It was located north of Union Street, west of Nevins Street, and next to Bond Street. Another mill, Denton's Mill, was built on Denton's Mill Pond. On May 26, 1664, some Brooklyn residents asked for permission to dig a canal. This canal would bring water to run the mill. Permission was given a few days later. Another mill, Cole's Mill, was near present-day 9th Street.

Farms and Oyster Fishing

In 1700, a settler named Nicholas Vechte built a farmhouse. It is now known as the Old Stone House. In 1776, during the Battle of Long Island, American soldiers fought British troops at this house. This helped General George Washington move his soldiers to safety. The house was at the edge of Denton's Mill pond.

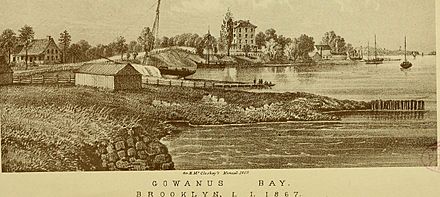

During this time, Dutch farmers lived along the marshland. They collected large oysters, which were sent to Europe. The Gowanus Bay's 6-foot (1.8 m) tides brought salty water into the creek. This created a good place for large shellfish to grow. Over time, the oysters became smaller. In 1774, New York made a law to widen the creek into a canal. This was to keep the waterway in good shape and tax people who used the land nearby.

Industrial Use and Pollution

From Creek to City Canal

By the mid-1800s, Brooklyn was growing fast. It was the third-largest city in the United States. The creek and farms became part of a city. The shoreline was used for transportation and as a way to get rid of waste. Richer people lived away from the smelly, lower areas. Factories that needed water for their work moved to the shoreline.

The mills on the Gowanus had public places where boats could load and unload goods. As more people moved to the area and the industrial revolution grew, there was a need for bigger docking areas. Colonel Daniel Richards, a local businessman, wanted to build a canal. This would help factories and also create new land by draining the marshes. This would make property values go up.

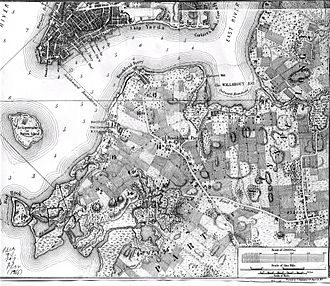

In 1849, the New York Legislature decided to make Gowanus Creek deeper. This would allow it to be used as a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) commercial waterway connected to Upper New York Bay. The digging was finished in 1860. Another law in 1867 allowed the canal to be made even deeper. Around the same time, a developer named Edwin Litchfield straightened the creek into a canal.

When the 1.8-mile-long (2.9 km), 100-foot-wide (30 m) canal was built, many designs were suggested. Some ideas included lock systems that would clean the water every day. But these ideas were too expensive. The final plan was chosen because it was cheap. Major David Bates Douglass designed the canal, which was mostly finished by 1869. The local residents of Brooklyn and the State paid for the construction.

Busy Factories and Heavy Pollution

Even though it was short, the Gowanus Canal was a very busy place for shipping in Brooklyn. At its busiest, up to 100 ships a day moved goods through it. Many industries grew around the canal. These included places for stone and coal, flour mills, cement factories, and gas plants. There were also tanneries, factories for paint, ink, and soap, machine shops, chemical plants, and sulfur producers. All these industries put a lot of pollution into the water and air. Chemical fertilizers were made along the canal after the American Civil War.

Coal processing was a major industry since 1869. By the late 1800s, there were 22 coal plants along the canal. These plants used a lot of water to turn coal into other products like gas. This gas was used for heating, light, and factory power. Waste water and coal tar (which has harmful chemicals) were dumped into the canal. Brooklyn's slaughterhouses also dumped blood and other waste into the canal.

The canal was only open at one end. People hoped the tides would be enough to clean the water. But the canal's walls stopped the strong tides from bringing fresh, oxygen-rich water from New York Harbor. With so much development around the Gowanus, too many chemicals and germs flowed into the canal. This used up the oxygen and made the canal smell bad. The amount of oxygen in the canal water was very low, much less than what is needed for life. The canal water turned a reddish-purple color. A thick, black mud called "black mayonnaise" built up at the bottom.

In 1887, New York State closed a pipe that flowed into the canal at Bond Street. By 1889, the pollution was so bad that the Legislature formed a group to study how to fix it. They thought the canal should be closed to ships and covered up. They also called the canal "a disgrace to Brooklyn" because of its terrible smell.

Trying to Fix the Pollution

The first step to fix the canal's pollution was building the Bond Street sewer pipeline in the 1890s. This sewer carried waste out into the harbor, but it wasn't enough. Then, the "Big Sewer" was built. It went from Prospect Heights to Gowanus and flowed into the canal near Butler Street. People thought this new sewer would drain a "Flooded District" and help move water in the upper Gowanus Canal. The tunnel was finished by 1893. But people complained their waste was not connected to it. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle first praised the sewer, but later called it an "engineering blunder" in 1898. They said it caused waste to flow back into the canal.

In the early 1900s, many new buildings were built in South Brooklyn. Factories brought many people, but the problem of wastewater drainage was not solved. All the waste from new buildings flowed downhill into the Gowanus. Rainwater also flowed from roofs into the canal. New sewer connections only made the problem worse by sending raw waste from farther away into the canal. Pollution, storm runoff, and sewage made the canal smell so bad it was called "Lavender Lake." Property owners even sued the city because of flooding problems.

By 1910, people complained that the canal's water was almost solid waste. This led to building a flushing tunnel that was 12 feet (3.7 m) wide. The Butler Street Pumping Station, a beautiful building, opened on June 21, 1911. The new flushing tunnel connected to this station. At first, the tunnel brought clean water from the Buttermilk Channel (between Brooklyn and Governors Island). It sent this clean water into the Gowanus Canal. But the flushing tunnel also failed. Many problems happened through the 1960s. One time, a city worker dropped a manhole cover, badly damaging the pump system. The system was already damaged by salty water. The Clean Water Act of 1972 had not yet been passed. The city did not have money to fix the problem. So, the canal's water stayed still and was not used for many years.

A Place for Dumping

There is a story that the canal was used by the Mafia to dump things. News reports say that bodies of a criminal in the 1930s and a union leader in the 1940s were found in the Gowanus Canal. In a 1998 movie about the canal, two police officers talked about finding a suitcase with human body parts in the water. Fishermen had found it.

Not just people, but also boats were lost in the canal. For example, on January 2, 1889, a tugboat sank during a storm, but the crew escaped. On May 10, 1892, a canal boat with coal sank. On December 31, 1903, a dredge (a machine for digging) was found sunk, and a worker was missing and thought to have drowned.

Less Use and More Decline

After World War I, six million tons of goods were moved through the canal each year. It became the busiest commercial canal in the country, and probably the most polluted. The large amount of waste flowing into it meant it had to be dug out often to keep boats moving. By the 1950s, Brooklyn's fuel industry was changing from coal to oil and natural gas. These were moved by bigger waterways or pipelines. In 1951, the Gowanus Expressway opened over the canal. This made it easier for trucks and cars to reach factories. The expressway carried 150,000 vehicles daily, which added tons of pollution to the air and water below. Around this time, waste from the Gowanus Canal was sent to treatment plants near the Buttermilk Channel.

In the early 1960s, containerization (using large containers for shipping) grew. This led to fewer factory jobs along the water. The canal's industries were also affected. The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) finished its last major digging of the canal in 1955. Soon after, they stopped digging regularly because it was too expensive. The fan that brought water from Buttermilk Channel into the flushing tunnel broke in 1963, and the tunnel closed. A year later, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opened. This meant trucks could use the bridge and Interstate 278 to ship goods. So, industrial boats no longer needed to use the canal.

With the city's waste and pump systems failing, the Gowanus Canal became a place for dumping. It stayed that way for almost 30 years. By 1993, only one company actively used the canal for shipping. Only three of the bridges would open for that company's boats. The few remaining barges mostly carried fuel oil, sand, gravel, and scrap metal. The canal still serves as a port for moving goods in and out of Brooklyn.

Cleaning Up the Canal

Early Cleanup Efforts

People have often called for improving the Gowanus area's economy and environment. The first major U.S. law to deal with water pollution was the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. Later, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created in 1970. The Clean Water Act was passed in 1972.

Starting in the 1960s, local people formed the Carroll Gardens Association (CGA). They wanted to improve the area, including cleaning up the Gowanus Canal. A long-time restaurant owner, Nick Monte, called it a "stinking, cancerous sore." CGA founder Salvatore "Buddy" Scotto Jr. called the canal "the most polluted waterway in the world." He said it was the reason for the area's economic problems. In 1971, New York City held meetings about a project to renew the Gowanus area, but they didn't fund it.

In 1974, Scotto brought scientists from New York City Community College to test the canal's water for bacteria. They found organisms that cause diseases like typhoid, cholera, dysentery, and tuberculosis. The next year, money was found for a first look at the canal. They found almost no oxygen, lots of raw sewage, grease, oil, and sludge. In 1978, construction began on the Red Hook Sewage Treatment plant. This plant had been planned since the 1950s.

A full study of the canal was published in 1981. It showed that on an average day, more than 13,000,000 US gallons (49,000,000 L) of raw sewage flowed into it. The report also showed that fewer industries were using the canal. The number of factories using the canal dropped from nearly fifty in 1942 to six in 1981. The amount of goods moved through the canal was more than 55% lower. The number of times the bridges opened dropped by almost 70%. The report suggested many things, including fixing the flushing tunnel to add more oxygen to the water.

In 1987, the Red Hook Treatment Plant opened. This plant, costing $375 million, took more sewage away from the canal. With this plant, New York City stopped dumping raw sewage into waterways during dry weather. Now, sewage only overflows during rainstorms. The next year, a sewage pipe was put inside the flushing tunnel. But an engineer said it was so badly installed that it broke "almost immediately." The city tried to fix it in 1998 but failed. It was finally fixed in 1999. Engineers changed the direction of the tunnel's fan. Before, water from the canal went into the Buttermilk Channel. Now, water from the channel went into the Gowanus Canal.

Superfund Cleanup Plan

Planning the Cleanup

In 2002, the USACE and the DEP agreed to work together on a $5 million study. This study would look at ways to restore the Gowanus Canal's natural environment. It would consider digging out pollution and restoring wetlands. The DEP also started a project to meet the city's duties under the Clean Water Act.

In early 2006, the problem of waste water came up during a debate about a planned arena for the Brooklyn Nets. This project, called Pacific Park, would include a basketball arena and 17 tall buildings. The extra waste water would flow into old sewers that overflow when it rains. The Gowanus Canal has 14 places where combined sewers overflow. People worried that the extra waste water from the arena would cause more frequent overflows into the canal.

In March 2009, the EPA suggested that the canal be listed as a Superfund cleanup site. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) agreed. They had asked the EPA for help with the canal's pollution. In May 2009, the city opposed the Superfund listing. For the first time, it offered to create its own cleanup plan. The city said it could clean up the canal faster than the EPA. It would use taxpayer money from the state and city. The EPA would get money from the companies that caused the pollution. The nonprofit Gowanus Canal Conservancy was also started in 2009. It partnered with the EPA, the NYCDEP, and groups like Riverkeeper. On March 4, 2010, the EPA announced that the Gowanus Canal was on its Superfund National Priorities List. After this, the USACE stopped their study and gave all their research to the EPA.

At first, local residents didn't like the EPA's cleanup ideas. They worried that the toxic waste dug from the canal would be put in nearby public areas. By 2013, the NYCDEP planned to reduce sewage in the canal by fixing the tunnel that brings fresh water into it. This repair would help, but not completely solve, the sewage problem. On September 27, 2013, the EPA approved a cleanup plan for the Gowanus Canal. The plan would cost $506 million and be finished by 2022. It divided the canal into three parts. The plan has three steps: digging out polluted mud from the bottom, covering the dug areas, and controlling sewage overflows to stop future pollution. It also involves digging out and restoring parts of old basins. Companies responsible for the pollution, like Brooklyn Gas and Electric (now National Grid) and New York City, are expected to pay for the cleanup.

The EPA suggested seven plans for the cleanup. In 2014, the EPA showed a plan for holding toxic mud in the canal. The Village Voice reported two plans were most likely. They would take ten years and cost about $350–$450 million. The first step was digging, planned for 2016. The second step was to put down a "cap." One idea was a concrete cap. The other was a cap with layers of clay (to absorb pollution), sand, and rocks. The multi-layered cap was chosen. However, some worried the cleanup could be a health risk.

Cleanup Begins

In early 2017, people worried that money for the Gowanus Canal cleanup might be cut. This was because President Donald Trump's government was reducing the EPA's budget. However, EPA administrator Scott Pruitt approved the funding. He said Superfund cleanups should be a top priority.

Work on the cleanup started in October 2017. At that time, it was expected to cost $506 million. The first part of a pilot study at the canal's Fourth Street Turning Basin began in December 2016. It was delayed while walls were being built along the canal's banks. The pilot digging found old items like a crash boat from World War II, wooden bobbins for textiles, and 19th-century wagon wheels. These items had to be cleaned before experts could study them. In July 2018, during the pilot study, the walkway near Whole Foods was damaged by a contractor. The main cleanup was expected to start in 2020 and finish two years later. On January 28, 2020, the EPA gave a formal order to start the first phase of the $506 million cleanup. This $125 million first phase would begin in September 2020 and last 30 months.

Cleanup Parts

EPA's Treatment Plan

The canal's toxic mud layer is about 10 feet (3.0 m) thick on average. In some places, it is 20 feet (6.1 m) deep. As part of the Superfund cleanup, the EPA will remove about 307,000 cubic yards (235,000 m3) of very polluted mud from the upper and middle parts of the canal. They will also remove 281,000 cubic yards (215,000 m3) of polluted mud from the lower part. This mud will be treated at a special facility away from the canal.

Then, where pollution has soaked into the mud below, the EPA will cover the dug areas with layers of clean material. These layers include an "active" layer of special clay. This clay will remove pollution that might rise from below. On top of the clay is an "isolation" layer of sand and gravel. This layer will make sure the pollution is not exposed. Next, an "armor" layer of heavier gravel and stone will stop boats and currents from washing away the layers below. The top layer will be enough clean sand to fill gaps in the stones. This will also make the canal bottom deep enough for plants and animals to live there again. In the middle and upper parts of the canal, where liquid coal tar has soaked into the natural mud, the EPA will mix it with concrete. These areas will then be covered with the multi-layer caps.

The Superfund plan requires the EPA to get money from the "Responsible Parties." These are the companies and government groups that caused the pollution. Over 30 companies, as well as New York City and the United States Navy, are responsible. Some companies, like Brooklyn Union Gas, no longer exist or have changed names. If these companies were bought by others, the new owners are expected to pay. The EPA Superfund report named National Grid (which bought Brooklyn Union Gas's successor, KeySpan) and the New York City government as the main responsible parties.

Flushing Tunnel Reactivated

According to the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, plans to restart the flushing tunnel pump were made in 1982. Different things caused the project to be delayed until 1994. The tunnel was finally restarted in 1999. The new design used a 600 horsepower (450 kW) motor. It pumped about 200,000,000 US gallons (760,000,000 L; 170,000,000 imp gal) of aerated water (water with air in it) each day from the Buttermilk Channel into the canal. Even though water was flowing, tides meant it could only be pumped 11 hours a day. The water quality improved when the pump was working.

In 2010, New York City started a four-year project to upgrade and restart the flushing tunnel. The New York Times said the plans included rebuilding the motor pit and replacing the propeller. They would also clean and fix the inside of the tunnel. The broken sewage pipe would be replaced and covered in concrete to improve water flow. They also planned to reduce sewage overflow into the canal by making a nearby pumping plant bigger. A main goal was to increase oxygen in the water. The original plans were changed in 2012 after Hurricane Sandy. This was to protect important equipment from flooding. In 2014, after much of the work was done, the tunnel was restarted. It cost $177 million.

Managing Stormwater

Throughout its history, the Gowanus Canal's sewage problems have been made worse by stormwater. For years, heavy rains have flooded streets and caused sewage pipes to overflow. This adds to the canal's pollution. Much of the Gowanus Canal area is at sea level and at risk for flooding. To help prevent flooding, the city is investing in different ways to manage stormwater. One improvement is creating special gardens along sidewalks called bioswales. These absorb stormwater and reduce sewer overflows into the canal. The Gowanus Canal Conservancy, a community group, helps take care of these bioswales. In 2015, the city built Sponge Park along the canal's western bank. This park also collects stormwater, soaking up pollution before it enters the canal.

Starting in 2017, the City's Department of Environmental Protection built several miles of high-level storm sewers (HLSS). These sewers stop stormwater from flooding the city's sewage system. The new storm sewers carry stormwater from new and old collection areas. This stops it from entering the sewage system. The first part, south of Douglass Street, was supposed to be finished by summer 2018. A second part north of Douglass Street would be built from 2018 to 2020. These HLSS, built in a 96-acre (39 ha) area, are planned to capture half of the stormwater in the Gowanus Canal's watershed.

Also in 2017, New York City released plans to build two combined sewer overflow facilities along the canal. These would help manage stormwater. The first facility, the "Head End Site," will be at the very north end of the canal. It will handle sewage from the Red Hook Watershed, which is the land around the canal's western bank and north of its start. The second facility, the "Owls Head Site," will be at Second Avenue and Fifth Street. It will clean water from the Owls Head watershed, which is the land from the eastern bank to Prospect Park. These new facilities are required by an agreement between the city and the EPA.

By February 2019, the EPA and the city disagreed on how to store untreated sewage. The EPA wanted to send the sewage to new tanks along the canal. This would be cheaper and finished by 2027. However, the city suggested sending untreated sewage into a new tunnel. This would be more expensive and finished in 2030.

What the Canal is Used for Today

Groups that help people get access to the water and learn about the canal include the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club (started in 1999) and The Urban Divers Estuary Conservancy (started in 1998). In 2003, over 1,000 people took part in Canoe Club programs, making more than 2,000 trips on the canal.

In 1975, the city government took over a site at Smith and 4th Streets. They said it was a public place for "public recreation space." Even though it's legally a public place, developers have kept suggesting other uses for the site. National Grid is responsible for cleaning up the pollution left there from years of making coal gas. Once it's clean, the site will be given to the New York City Parks Department.

Activism and Art

In November 2006, a festival called HABITATS celebrated the Gowanus Canal. It had environmental talks, art, educational programs, and walks around the area. The canal has also been home to different art groups. ISSUE Project Room once held art events in a converted silo along the canal. The Yard, an outdoor concert space, opened in summer 2007 near the Carroll Street Bridge. It closed at the end of summer 2010.

On Earth Day in 2015, environmental activist Christopher Swain swam through the Gowanus Canal. He did this to raise awareness about the cleanup work. He wore protective swimwear, but some of his skin was exposed to the waste. He used things like antibacterial lotion and hydrogen peroxide mouthwash to protect himself. Swain had swum in many polluted waterways. He said the Gowanus was the dirtiest, like "swimming through a dirty diaper."

Water Quality

Different parts of the Gowanus Canal are like small microclimates. They can have very different conditions and types of pollution. Overall, the water is not safe to drink or swim in. People are told not to touch the canal's water. The Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club encourages people to canoe on the canal. This is partly to encourage people to help clean up the area. The Urban Divers Estuary Conservancy allows careful diving using special suits. Divers must go through strict cleaning procedures afterward. Fish caught in the canal are usually toxic and not safe to eat much of. 2018, birds have started returning to the canal. Some hope this means the water quality is getting better for wildlife.

Descriptions of the Water

People have described the canal's water quality over time. In the 1800s, it was reddish-purple from coal and slaughterhouse waste. In the 1900s, it was a lighter purple, leading to its nickname "Lavender Lake." The author H. P. Lovecraft described "the lapping oily waves at its grimy piers." In 1999, the water was described as "green with a white undertone, like cream-infused coffee." A 2013 description said the canal's "modern" color was gray-green. In 2017, two long-time residents remembered the canal being black in the 1950s. They said, "All you could see was a big cesspool, and bubbles coming up."

The surface of the Gowanus Canal's water often has a shiny, colorful film. This suggests the presence of oil, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), coal tar, and other industrial waste. As recently as December 2009, a report noted "spotty, iridescent, and platy sheens," fecal matter, oily water, and blobs of liquid pollution in different areas of the canal. Photographers have also taken artistic pictures of the canal.

The cloudy water stops sunlight from reaching the bottom. Sunlight is needed for water plants to grow. Gas bubbles rising from the water show that sewage sludge is breaking down. On a warm day, this causes the Gowanus Canal's strong, bad smell. One reporter said the smell was "like sticking your head into a rubber boot filled with used motor oil and rotten eggs." Another said it was "less a scent than an assault that reaches in to choke the throat." Sometimes it smells like petroleum and dead fish. Reports say the smell has lessened in recent years as oxygen levels in the water have gone up.

The murky depths of the canal hide its industrial past. It contains cement, oil, mercury, lead, many volatile organic compounds, PCBs, and coal tar. A thick layer of "black mayonnaise" at the bottom was described in the 1800s and is still there. In some places, it is up to 20 feet (6.1 m) deep.

Scientific Tests

Since the 1970s, different groups have taken measurements of the canal's water quality. These include government, university, and citizen groups. There has not been a clear, long-term program to track water quality because there is no money for it.

The canal has high levels of pathogens (germs), many of which are harmful to humans. The 1974 report by scientists found that the water contained germs that cause typhoid, cholera, dysentery, and tuberculosis. Also, a 2003 report on New York Harbor showed that the Gowanus Canal had the highest level of germs of any place in the entire harbor. Scientist Nasreen Haque and her classes have also tested water from the Gowanus.

Waste from living things is also common in the canal. In 2009, a local environmental group called Riverkeeper tested canal water after heavy rains and sewage flooding. They found very high levels of Enterococcus bacteria. Levels above 104 cells per 100 milliliters are considered unsafe. The canal had 17,329 cells per 100 milliliters. Enterococcus shows that other harmful germs might be present. As of 2013, waste was still present in Gowanus water at very high levels.

Low levels of dissolved oxygen in the canal's waters have been a problem since before World War I. The lowest level of oxygen needed for healthy sea life is about 4 parts per million. As early as 1909, it was reported that the canal had no oxygen at all. In 1975, there was still a severe lack of oxygen. This meant the water could not support plants or fish. In 1999, just before the flushing tunnel was restarted, The Environmental Magazine reported that oxygen levels were about 1.5 parts per million. This number was still used fourteen years later. However, by 2008, nine years after the flushing tunnel reopened, scientist Kathleen Nolan and students found that oxygen levels had greatly increased. In 2014, a NYSDEC representative said that dissolved oxygen levels were between 9 to 12 mg/l (5.2×10−6 to 6.9×10−6 oz/cu in), or about 9–12 parts per million.

The EPA and other groups have done detailed studies of the "black mayonnaise" at the bottom of the canal. The 2012 Superfund plan also includes detailed studies of the risks from pollutants in the mud, water, and surrounding area.

The Gowanus Canal's pollution has also spread to Gowanus Creek, at the mouth of the canal. In 1982, the USACE reported that there was no oxygen in the creek. It also had high levels of germs and large amounts of oil and grease.

Wildlife in the Canal

Originally, the marshland and freshwater springs that flowed into the Atlantic Ocean had huge oyster beds. As late as 1911, people reported fishing and collecting clams in the Gowanus Canal. By 1927, all of New York's oyster beds had closed. This was due to habitat destruction, too much harvesting, and pollution.

People have tried to bring back oysters and other shellfish to the canal. This is because they can filter out toxins and help clean the water. One oyster can clean as much as 50 US gallons (190 L) of water a day. The NY/NJ Baykeeper environmental group gives oysters to volunteers. These volunteers then check the oysters' health and growth in local waterways. They have helped people partner with teachers, students, and the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club. Together, they put and watch oyster cages in the canal. In 2012, a landscape architect named Kate Orff suggested a park design with a living reef containing oysters, mussels, and eelgrass. As part of a pilot program, ropes were hung from a pier to attract ribbed mussels.

When the flushing tunnel was fixed, it brought more oxygen to the canal. This has helped some water life return. Within months of the tunnel reopening in 1999, John C. Muir saw pink jellyfish, blue crabs, and different kinds of fish. By 2009, white perch, herring, striped bass, and anchovies were living in the water. In 2014, the Gowanus Canal Conservancy reported that herons, egrets, bats, and Canada geese were living nearby. However, wild animals in the Gowanus Canal may have problems with reproduction. Creatures living in the canal often live shorter lives than the same animals living elsewhere in New York Harbor.

About 15 kinds of edible fish and shellfish can be found in the canal, but they are toxic. The shellfish have toxins and are unsafe to eat, according to a 2012 report. However, signs posted in 2018 say that men over 15 and women over 50 can safely eat up to six blue crabs from the Gowanus Canal each week. But women under 50 and children under 15 should not eat the canal's blue crabs at all.

Water mammals have been seen in the canal only rarely, and usually when they are in trouble. A harp seal was seen in the canal in 2003. Its flippers were bloody, but it survived and was moved to the Long Island Sound. In 2007, a young minke whale ended up in the canal because of heavy storms. The whale, soon called "Sludgy," could not get out and died. A study of Sludgy showed that the whale was already sick. On January 26, 2013, a dolphin entered the canal at low tide. It could not get out and died. A study showed it was middle-aged and sick before it got trapped. It had kidney stones, stomach ulcers, and parasites.

New Forms of Life

Even though the Gowanus Canal is harmful to humans, it might be creating new kinds of organisms. In 2008, Nasreen and Nilofaur Haque reported seeing white clouds of "biofilm" floating above the mud at the bottom of the canal. Studies suggested that this "white stuff" is a mix of bacteria, protozoa, chemicals, and other things working together. The parts of the mixture worked together to find food. The living parts exchanged genes and made a substance that acts like an antibiotic. This protected them from toxins in the water. The Haques started studying a type of bacteria from the canal to learn what makes bacteria resistant. This research might help create new antibiotic drugs.

In 2014, volunteers and scientists wore Hazmat suits to take samples of the black mayonnaise from the canal. They took out DNA and studied it. Ellen Jorgensen, a director at Genspace, said that the group could not identify half of the DNA. They found "42 kinds of bacteria, two viruses, and five life forms from the domain Archaea." Many of these were specially adapted to the harsh environment of the Gowanus Canal. Some microbes, called Methylococcaceae, found in the Fourth Street Basin, eat methane. Others, called Desulfobacterales, take in sulfate and release hydrogen sulfide. This adds to the Gowanus’ rotten egg smell.

Scientists were also interested in studying the canal's unique groups of microbes. These naturally growing bacteria help clean up the Gowanus’ pollutants. Understanding how they live with and break down toxic compounds might lead to new ways to clean up pollution.

In Popular Culture

In November 2015, Gothamist posted a video. It showed a fisherman saying he had just caught a three-eyed catfish in the canal. Many news outlets shared the story. However, experts doubted the fish story. A New York Times article said the three-eyed catfish was a trick made by the performance artist Zardulu.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Canal Gowanus para niños

In Spanish: Canal Gowanus para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |