Carol A. Barnes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carol A. Barnes

|

|

|---|---|

| Alma mater | University of California, Riverside University of Ottawa Carleton University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neuroscience, memory, learning |

| Institutions | University of Arizona |

| Doctoral advisor | Peter Fried |

Carol A. Barnes is an American neuroscientist. This means she is a scientist who studies the brain and nervous system. She is a special kind of professor, called a Regents' Professor, at the University of Arizona.

Since 2006, she has held an important position as the Evelyn F. McKnight Chair for Learning and Memory in Aging. She also directs the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute. Dr. Barnes has led the Society for Neuroscience, which is a big group for brain scientists. She is also a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a foreign member of the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters. In 2018, she was chosen to join the National Academy of Sciences, which is a very high honor for scientists in the U.S.

Dr. Barnes has written over 170 scientific papers. Her main research looks at how the brain and behavior change as people get older. Understanding these changes can help us learn more about brain diseases that happen with age, like Alzheimer's disease. She also created the Barnes maze. This is a special test used to check memory that relies on a part of the brain called the hippocampus.

Contents

Education and Early Career

Carol Barnes earned her first degree, a Bachelor of Arts in psychology, from the University of California, Riverside in 1971. She then went to Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, where she received her Master of Arts degree in psychology in 1972.

In 1977, she completed her Ph.D. in psychology, also from Carleton University. After her Ph.D., Dr. Barnes worked as a postdoctoral researcher. This means she continued her studies and research after getting her doctorate. She worked at Dalhousie University, the University of Oslo, and University College London.

Current Work and Teaching

Dr. Barnes is the Endowed Chair for Learning-Memory in Aging at The Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute. She is also a Regents Professor and director of a division at the University of Arizona in Tucson. This division focuses on neural systems, memory, and aging.

She is also part of the BIO5 Institute, which gets funding to support research. At BIO5, she works with students to study Alzheimer's disease and other brain conditions related to aging. Dr. Barnes also teaches classes on cancer biology, neuroscience, psychology, and how the body works.

Brain Research and Aging

Dr. Barnes has been a key part of the neuroscience research community for 40 years. Her research aims to understand how the brain ages and how this relates to thinking problems. Her interest in normal brain aging started when she noticed her own grandfather's memory was declining.

She uses animal models, like monkeys and rats, in her research. This helps her explore how memory is affected during normal brain aging. It also helps her understand the biological processes involved. The findings from her animal studies can lead to new treatments. These treatments aim to help older people keep their thinking skills for longer.

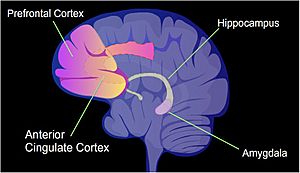

Dr. Barnes uses many different methods in her research. These include studying behavior, looking at brain structures, recording electrical activity in the brain, and examining molecules. Much of her work involves studying the hippocampus in the brains of rats and monkeys. She observes how brain cells signal each other and studies the genetic information within cells.

The Barnes Maze

To study how animals learn and remember locations, Carol Barnes created a special maze. This maze helps test if mice can remember where an escape box is on a platform. The Barnes maze is now a common tool for memory testing in labs.

She designed it in 1979 as a way to study memory without using rewards or punishments. This also helped reduce stress for the animals during the tests. The original maze was a round platform, about 122 cm across, raised 91 cm off the floor. It had 18 holes around the edge. Under one hole was a dark escape box, while the other holes led nowhere.

Her study had three parts. First, a mouse just had to find the escape box. Second, the escape box was moved to a new hole, and the old hole was covered. Third, the escape box moved again, but the old hole was not covered. Dr. Barnes and her team found that male mice generally did better. They also saw that younger mice performed better in all parts of the experiment. Older mice had trouble with the second and third parts. This showed that aging can affect spatial memory, which is memory for places.

Using special brain scans called MRI, Dr. Barnes and her team looked at the brains of normally aging rodents. They found that the size of the hippocampus did not change. However, the amount of grey matter in the outer part of the brain did change. This animal research helped scientists understand what a normally aging human brain might look like. They could then compare this to brains affected by Alzheimer's disease. The findings showed that while the hippocampus stays the same size with normal aging, its function might decrease compared to other brain areas.

Looking even closer at brain tissue, single-cell imaging showed three main types of cells in the hippocampus. When observing cell activity in rats, two types of cells, CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells, stayed active and kept their volume. But the number of granule cells in a part called the dentate gyrus decreased with age. The function of these cells also went down. This led Dr. Barnes's team to believe these gyrus cells are a "weak link" in the memory circuit of the hippocampus.

Primate Studies

Besides her work with rodents, Dr. Barnes has also used nonhuman primates, like macaque monkeys, to study normal aging. Her early work with macaques helped connect brain data from rodents with brain scan data from older humans.

In one study, Dr. Barnes and her team showed that older monkeys had trouble recognizing objects. They also found that older monkeys had fewer inhibitory neurons in the CA3 region of the hippocampus. These special neurons help control the activity of other brain cells. With fewer of them, the main brain cells in CA3 were more active than normal. This matches what brain scans show in older humans. Both fewer inhibitory neurons and increased activity in the hippocampus have been linked to poorer thinking skills.

In another important study, Dr. Barnes's team found that all mammals might use the same number of brain cells in the hippocampus to remember a single experience. This suggests that mammals use a steady amount of neurons to remember a similar virtual reality experience. However, because the hippocampus varies in size, the percentage of neurons used for memory differs. Rodents have the smallest hippocampus and use about 40% of their neurons for memory. Monkeys have a larger hippocampus and use about 4%. Humans have the largest hippocampus and use an estimated 2.5% for remembering experiences.

Dr. Barnes has also studied how executive functions change with normal aging. Executive functions are higher-level thinking skills like paying attention, making decisions, and controlling impulses. These skills are managed by the prefrontal cortex in the brain.

She focused on two parts of executive function in macaques:

- Attentional monitoring and updating: This is how we change our behavior when rules change. For example, if the correct choice in a game changes, this skill helps us adapt. Dr. Barnes found that older monkeys needed more tries to learn new rules. This suggests that this part of the executive system is affected by aging.

- Set shifting: This is the ability to switch attention between tasks while staying accurate. Dr. Barnes tested this by having monkeys recognize objects, then introducing new objects that required them to shift their focus. Surprisingly, older monkeys did better than younger ones on this task. This suggests that set-shifting skills might stay good or even improve with age.

A key discovery from these studies is that these two executive functions are separate systems. They are affected differently by age. This means that while the prefrontal cortex changes with aging, different parts of it show different patterns of change.

Finally, Dr. Barnes has studied how spatial networks and spatial memories change in aging macaques. Her team looked at brain activity in monkeys during different movements: in cages, sitting, walking on a treadmill, and walking freely. They found that younger monkeys had clear, distinct brain networks for each movement. However, older monkeys showed less distinct activity. This means the same general network was active for all conditions. This suggests that changes in these brain networks might explain why older individuals sometimes have trouble with spatial memory or get confused about places.

Supporting Others in Science

Dr. Barnes is known for helping women and people from less privileged backgrounds succeed in neuroscience. In 2010, she received the Mika Salpeter Lifetime Achievement Award. This award honors scientists who have achieved a lot and have actively helped women advance in neuroscience.

She also takes part in programs that support students, such as the NIH Disadvantaged High School Student Research Program and the McNair Achievement Program. In 2013, Dr. Barnes gave a special speech called "The Evolving Face of Neuroscience: Role of Women and Globalization."

Awards and Honors

- 1969: National Science Foundation Summer Research Fellowship

- 1972–74: Ontario Graduate Fellowship

- 1979–81: NIH National Research Service Award

- 1981–82: NATO Postdoctoral Fellowship in Science

- 1984–89: Research Career Development Award

- 1989–94: ADAMHA Research Scientist Development Award, National Institute of Mental Health

- 1994–99: ADAMHA Research Scientist Development Award, National Institute of Mental Health

- 2004–present: Foreign Member, Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters Natural Sciences

- 2004–14: MERIT Award, National Advisory Council on Aging

- 2004–14: Regents Professor, University of Arizona

- 2006–present: Endowed Chair: Evelyn F. McKnight Chair Learning and Memory in Aging

- 2009–present: Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science

- 2010: 2009 APA Division 6 D.B. Marquis Behavioral Neuroscience Award

- 2010: 2010 APA Division 6 D.B. Marquis Behavioral Neuroscience Award for Behavioral Neuroscience

- 2010: Mika Salpeter Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2011–present: Galileo Fellow, College of Science, University of Arizona

- 2013: Ralph W Gerard Prize in Neuroscience

- 2014: APA Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions

- 2017: Quad-L Award

- 2017: MOCA Local Genius Award

- 2018: National Academy of Sciences

Images for kids