Central Synagogue (Manhattan) facts for kids

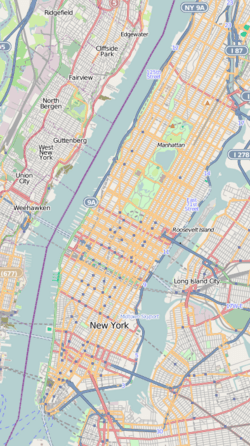

Quick facts for kids Central Synagogue |

|

|---|---|

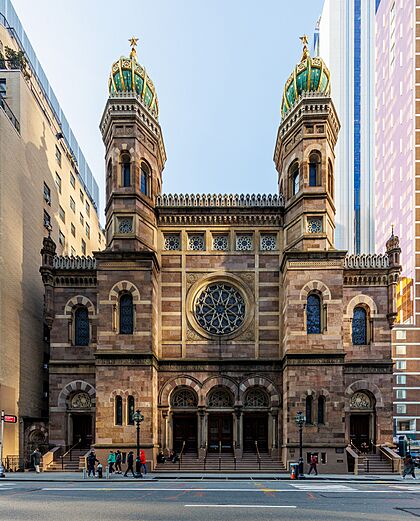

The synagogue on Lexington Avenue, in 2023

|

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Synagogue |

| Leadership | Clergy:

|

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 646–652 Lexington Avenue |

| Municipality | Midtown Manhattan, New York City |

| State | New York |

| Country | United States |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Henry Fernbach |

| Architectural type | Synagogue |

| Architectural style | Moorish Revival |

| Date established |

|

| Groundbreaking | December 14, 1870 |

| Completed | April 19, 1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | East (main facade) |

| Capacity | 1,400 |

| Length | 140 ft (43 m) |

| Width | 93 ft (28 m) |

| Height (max) | 112 ft (34 m) |

| Materials | Brownstone, light stone |

Central Synagogue is a famous place of worship for Reform Jews in New York City. It is located at 652 Lexington Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. The synagogue is known for its beautiful building and long history.

The current group of worshippers, called a congregation, was formed in 1898. It was created when two older synagogues, Shaar Hashomayim and Ahawath Chesed, joined together. The building itself was built between 1870 and 1872 for the Ahawath Chesed congregation.

The building was designed by architect Henry Fernbach in a style called Moorish Revival. This style was inspired by buildings in Spain and North Africa. Because of its special design and history, the synagogue is a New York City designated landmark and a National Historic Landmark.

Contents

History of the Synagogue

Central Synagogue was created from two separate Jewish congregations that started in the 1800s on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. At that time, many Jewish people from Germany and Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) were moving to New York.

The First Congregations

The first congregation, Shaar Hashomayim (which means Gates of Heaven), was started in 1839 by Jews from Germany. They first met in a small building on Attorney Street. Over time, they moved to different locations as their community grew.

The second congregation, Ahawath Chesed (meaning Love of Mercy), was started in 1846 by Jews from Bohemia. They began as a small club and officially formed their congregation in 1848. Like Shaar Hashomayim, they also moved several times as more people joined.

Building a New Home

By the 1860s, many members of Ahawath Chesed had moved to a wealthier part of Manhattan called Midtown. They decided to build a grand new synagogue there. In 1869, they bought land at the corner of Lexington Avenue and 55th Street.

They hired the architect Henry Fernbach to design the new building. The cornerstone was laid in 1870, and the synagogue was completed and opened on April 19, 1872. The beautiful new building helped attract many new members to the congregation.

Joining Together

In 1898, the two congregations, Ahawath Chesed and Shaar Hashomayim, decided to merge. They became one large congregation called Ahawath Chesed Shaar Hashomayim. They used the beautiful building on Lexington Avenue for their services.

Over time, people started calling it "Central Synagogue" because of its location in the city. The name became official in 1974.

A Century of Change

Throughout the 20th century, Central Synagogue continued to grow and change. It became a very important center for Jewish life in New York City.

New Leaders and Ideas

In 1918, Rabbi Nathan Krass became the leader. He was a popular speaker, and many people, both Jewish and non-Jewish, came to hear him. During this time, the synagogue's membership grew so much that there was a waiting list to join.

In the 1920s, the synagogue briefly merged with another group, the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue. However, they had different ideas about worship, so they decided to separate after a few years.

From 1925 to 1959, Rabbi Jonah Wise led the congregation. He helped the synagogue through difficult times, including the Great Depression and World War II. During the war, the synagogue helped Jewish refugees who were escaping from Europe.

A Devastating Fire and Rebirth

A terrible event happened on August 28, 1998. While the synagogue was being repaired, a fire accidentally started. The fire caused massive damage to the building. The roof collapsed, and the beautiful interior was destroyed.

Luckily, important items like the sacred Torah scrolls were safe. People from all over the world offered money and support to help rebuild. The congregation decided to restore the synagogue to look exactly as it did when it was first built.

After three years of hard work, the restored synagogue reopened on September 9, 2001. The restoration was a great success and won many awards.

The Synagogue Today

Since 2014, Central Synagogue has been led by Senior Rabbi Angela Buchdahl. She is the first woman and the first Asian-American to hold this position at the synagogue.

Today, Central Synagogue is one of the largest and most active Reform congregations in the country. It has thousands of members. In addition to regular worship services, it offers many programs for children and adults, including a school, concerts, and charity work.

The synagogue also livestreams its services online. This allows people from all over the world to be part of the community.

Architecture and Design

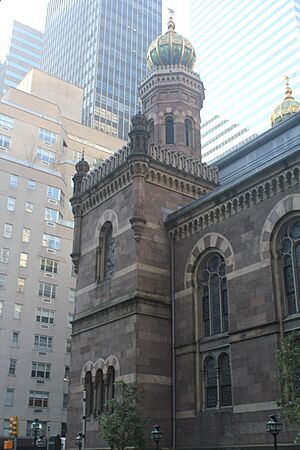

The building is famous for its Moorish Revival style. This style uses designs from historic Spanish and Middle Eastern buildings. It is one of the oldest and most beautiful synagogue buildings in the United States.

The Exterior

The outside of the building is made of brownstone with trim of a lighter-colored stone. The most noticeable features are the two tall, octagonal towers. Each tower is topped with a large, onion-shaped dome decorated with gold leaf.

The main entrance on Lexington Avenue has a large, circular rose window made of stained glass. The sides of the building also have tall stained-glass windows that let light into the main sanctuary.

The Interior

The inside of the synagogue is just as stunning as the outside. The walls and ceiling are covered with colorful stencils in shades of blue, red, and gold. There are over 200 different patterns, creating a rich and detailed look.

The main room, or sanctuary, is large and open, similar to a church. It has a high ceiling painted dark blue with gold stars. Wooden pillars separate the main central area (the nave) from the aisles on each side. At the front is the bema, a platform where the rabbis lead the service, and the Torah ark, which holds the sacred scrolls.

The synagogue can seat about 1,400 people. It also has a large pipe organ, which was installed in 2002 to replace the one lost in the fire.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sinagoga Central para niños

In Spanish: Sinagoga Central para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |