Charles Lever facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Lever

|

|

|---|---|

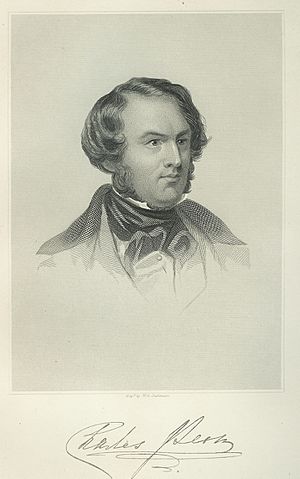

Lever in 1858

|

|

| Born |

Charles James Lever

31 August 1806 Dublin, Ireland

|

| Died | 1 June 1872 (aged 65) Trieste, Italy

|

| Nationality | Irish |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Dublin |

| Occupation | Novelist, raconteur |

| Spouse(s) |

Catherine Baker

(m. 1833–1870) |

Charles James Lever (born August 31, 1806, died June 1, 1872) was a famous Irish writer. He wrote many novels and was known for being a great storyteller. Another famous writer, Anthony Trollope, once said that Lever's books were just like listening to him talk!

Contents

About Charles Lever

His Early Life and Adventures

Charles Lever was born in Dublin, Ireland. His father, James Lever, was an architect and builder. Charles went to private schools and later studied medicine at Trinity College, Dublin. He earned his medical degree in 1831.

During his time at college, Charles had many exciting adventures and played lots of pranks. He even used some of these experiences in his novels later on! For example, the character Frank Webber in his book Charles O'Malley was based on a college friend. Charles and his friend would even sing songs they made up on the streets of Dublin to earn some money.

Before he became a serious doctor, Charles traveled to Canada. He worked as a surgeon on a ship carrying people who were moving there. He wrote about some of these experiences in his books Con Cregan and Roland Cashel. In Canada, he explored the wild backwoods and even spent time with a tribe of Native Americans.

When he returned to Europe, he pretended to be a student from the University of Göttingen and visited other universities, including the University of Jena, where he saw the famous writer Goethe. He really enjoyed German student life, and some of his songs were inspired by their student tunes.

After getting his medical degree, Charles worked as a doctor in County Clare and then in Portstewart, County Londonderry.

Becoming a Writer

In 1833, Charles married his first love, Catherine Baker. In 1837, he started publishing his first novel, The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer, in the Dublin University Magazine. This book was a collection of funny and exciting stories, mostly about Ireland. Charles was surprised by how popular it became! He once said, "If this sort of thing amuses them, I can go on for ever."

Charles lived in Brussels for a while, working as a doctor. Brussels was a great place for him to observe different kinds of people, especially retired military officers who loved to tell stories about their adventures. He used these observations in his books.

Even though Charles had never been in a real battle himself, his next three books were full of amazing military scenes. These books were Charles O'Malley (1841), Jack Hinton (1843), and Tom Burke of Ours (1844). His descriptions of battles were so lively that even famous military leaders like the Duke of Wellington enjoyed them!

In 1842, Charles returned to Dublin to become the editor of the Dublin University Magazine. He met many other Irish writers and thinkers there. He even welcomed Thackeray, another famous author, to his home near Dublin. Thackeray noticed that beneath all of Charles's fun and humor, there was also a touch of sadness, which he felt was common in Irish writing.

However, keeping up with his busy life in Dublin, with many guests and horses, made it hard for Charles to focus on writing. So, in 1845, he left his editor job and moved back to Brussels.

Travels and Later Books

After leaving Dublin, Charles traveled a lot around central Europe with his family. He would stop in different places, sometimes renting large castles, and entertain many guests. For example, in 1846, he hosted Charles Dickens and his wife. Dickens later published one of Charles Lever's novels, A Day's Ride, in his own magazine.

Charles continued to write many novels during his travels, such as The Knight of Gwynne (1847), The Confessions of Con Cregan (1849), and Roland Cashel (1850). However, he started to lose some of his earlier joy in writing. He felt that life offered less excitement as he got older.

In 1863, his son, Charles Sidney Lever, passed away and was buried in Florence, Italy.

Later Life and Passing

Even though Charles felt sad at times, he remained very witty and was still popular at social gatherings because of his stories. In 1867, he was offered a job as a consul (a government official who helps citizens abroad) in Trieste, Italy. It was a good job with a good salary, but Charles often found Trieste to be a lonely and boring place.

He continued to write, producing books like The Fortunes of Glencore (1857), Tony Butler (1865), and Lord Kilgobbin (1872). He also wrote a column called Cornelius O'Dowd for Blackwood's.

Charles was deeply affected by the death of his wife in 1870. He visited Ireland the next year, but his health was declining. He passed away suddenly and peacefully from heart failure on June 1, 1872, at his home in Trieste. His daughters were well taken care of.

What People Thought of His Work

Anthony Trollope greatly admired Charles Lever's novels, saying they were just like his lively conversations. Charles was a natural storyteller, able to describe things easily and lead up to a good punchline. His most exciting books, like Lorrequer and O'Malley, are like a series of adventures in the life of a main character, rather than one long, connected story.

His characters were often simple but memorable. For example, he created characters like Frank Webber, Major Monsoon, and Micky Free, who was called "the Sam Weller of Ireland" (meaning he was a very popular and witty servant character).

Some people believed that Charles Lever's later books, while perhaps better written, didn't have the same wild energy as his earlier ones. However, his military scenes in books like O'Malley and Tom Burke are considered some of his best work. His talent for creating fun and lively scenes made his early books, especially with Phiz's illustrations, feel full of entertainment.

Superior, it is sometimes claimed, in construction and style, the later books lack the panache of Lever's untamed youth. Where else shall we find the equals of the military scenes in O'Malley and Tom Burke, or the military episodes in Jack Hinton, Arthur O'Leary (the story of Aubuisson) or Maurice Tiernay (nothing he ever did is finer than the chapter introducing "A remnant of Fontenoy")? It is here that his true genius lies, even more than in his talent for conviviality and fun, which makes an early copy of an early Lever (with Phiz's illustrations) seem literally to exhale an atmosphere of past and present entertainment. It is here that he is a true romancist, not for boys only, but also for men.

Lever's lack of artistry and of sympathy with the deeper traits of the Irish character have been stumbling-blocks to his reputation among the critics. Except to some extent in The Martins of Cro' Martin (1856) it may be admitted that his portraits of Irish are drawn too exclusively from the type, depicted in Sir Jonah Barrington's Memoirs and already well known on the English stage. He certainly had no deliberate intention of "lowering the national character". Quite the reverse. Yet his posthumous reputation seems to have suffered in consequence, in spite of all his Gallic sympathies and not unsuccessful endeavours to apotheosize the "Irish Brigade".

A collection of his novels in 37 volumes was published between 1897 and 1899, overseen by his daughter, Julie Kate Neville. The writer Henry Hawley Smart was said to have used Lever's work as a guide when he started writing his own sports novels. Charles Lever's books were also found on the family bookshelf of the famous playwright Eugene O'Neill, as mentioned in his play Long Day's Journey into Night.

See also

- Stage Irish

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |