Color book facts for kids

In the world of diplomacy (how countries talk to each other), a color book is a special collection of official letters and documents. Governments publish these books for different reasons. They might want to teach people about past events or explain their actions. Sometimes, they use these books to show their side of a story during a crisis or war.

The very first color books were the British Blue Books, which started way back in the 1600s. During World War I, many major countries had their own color books. For example, Germany had a White Book, Austria had a Red Book, and Russia had an Orange Book.

Especially during wars, color books were used as a type of propaganda. This means they tried to convince people that the government's actions were right. They also tried to blame other countries for problems. Governments carefully chose which documents to include and how to present them. This made the books powerful tools to spread their message.

Contents

What are Color Books?

The names for these books, like the British blue book, have been around for centuries. Many individual color books became common in the 1800s, especially during World War I. The general term "color book" came later. In German, "Rainbow book" was used in 1915, and "color book" in 1928. In English, "color book" has been used since at least 1940.

How Color Books Started

Early History

In the early 1600s, blue books first appeared in England. They were a way to share official letters and reports from diplomats. They got their name because they had blue covers. The Oxford English Dictionary first recorded this use in 1633.

During the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s, these books were published regularly. By the late 1800s, other countries in Europe started making their own versions. Each country picked a different color:

- Germany used white.

- France used yellow.

- Austria-Hungary used red (Spain and the Soviet Union later used red too).

- Belgium used gray.

- Italy used green.

- The Netherlands and Tsarist Russia used orange.

This idea even spread to other parts of the world. The United States used red, Mexico used orange, and countries in Central and South America used other colors. China used yellow, and Japan used gray.

The 1800s

The 1800s were a busy time for British Blue Books. Many were published in Great Britain. Their main goal was to give Parliament (the government's law-making body) the information it needed. This helped Parliament make decisions about foreign affairs.

How They Were Made

These books were usually created in one of three ways:

- By order of the King or Queen.

- By order of Parliament.

- In response to a request from the House of Commons or House of Lords.

Sometimes, pressure from Parliament would lead to papers being published that might not have been otherwise. Documents were often first printed on large, loose sheets of white paper. These were called White Papers. They were given to Parliament often without dates. This made it hard for historians later to know the exact order of events. Some of these documents were later reprinted and bound as "Blue Books" with their blue covers.

Important Leaders

No other European country published as many Blue Books as Great Britain. These books were meant to respond to what the public thought. Different leaders handled them in different ways.

George Canning (who was in charge from 1807–1809) created a new system. He used Blue Books to get public support for his ideas, like those about South America. Later, Lord Palmerston (who was in charge several times in the 1830s and 1840s) published many Blue Books. This time is sometimes called the "Golden Age" of Blue Books.

How Other Countries Reacted

When these books were published, not only Parliament and the public saw them, but other countries did too. Sometimes, a government might be embarrassed by information leaked by other countries. But they also shared information back. By 1880, there were some informal rules. Countries would usually talk to each other before publishing things that affected them. This stopped the books from being used as a weapon against other countries.

Before World War I

After 1885, things changed again. There was less pressure from Parliament to publish documents. Ministers became more private and shared less information. For example, Sir Edward Grey, who was in charge before World War I, was very secretive. Even though many publications still came out, they contained less diplomatic letters and more treaty texts.

World War I

The Start of the War

The killing of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, started a month of intense talks between Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, and Britain. This time is known as the July Crisis. Austria-Hungary believed that Serbian officials were involved in the killing. On July 23, they sent Serbia a very strict ultimatum (a final demand) to start a war.

This led to Austria getting its army ready. Then Russia did the same to support Serbia. Austria declared war on Serbia on July 28. More countries started getting their armies ready and sending warnings. Germany told Russia to stop getting its army ready and warned France to stay neutral. After many messages and misunderstandings, Germany invaded Luxembourg and Belgium on August 3–4. Britain then entered the war because of a treaty it had with Belgium from 1839. Europe was then in the Great War.

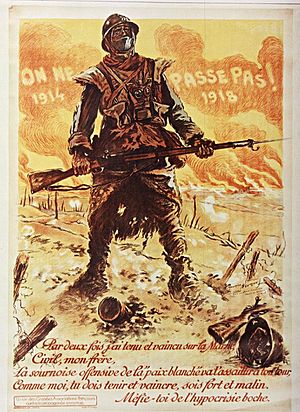

The Media Battle

As armies started fighting, governments began a "media battle." They tried to avoid blame for starting the war and instead blamed other countries. They did this by publishing carefully chosen diplomatic letters.

The German White Book was the first to appear on August 4, 1914. It had 36 documents. Within a week, most other fighting countries published their own books, each with a different color name. France waited until December 1, 1914, to publish its Yellow Book.

Other countries in the war published similar books:

- The Blue Book of Britain

- The Orange Book of Russia

- The Yellow Book of France

- The Austro-Hungarian Red Book

- The Belgian Grey Book

- The Serbian Blue Book

How Propaganda Was Used

World War I color books tried to make their own country look good and enemy countries look bad. They did this in many ways:

- Leaving things out: Not including documents that hurt their side.

- Picking only certain things: Only including documents that helped their side.

- Changing the order: Presenting documents in a different order to make it seem like events happened earlier or later than they did.

- Outright lies: Sometimes, they even changed the documents.

A mistake in the 1914 British Blue Book made it easy for German propaganda to attack it. This mistake then led to some wrong details in the French Yellow Book, which had copied them.

German propagandists called the Yellow Book a huge "collection of lies." They said France had given Russia full support. Germany tried to show it was forced into war because Russia got its army ready first. Russia, in turn, blamed Austria-Hungary. The documents from the Allied countries about the war's start were used in 1919. They helped create Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which said Germany and Austria-Hungary were solely responsible for the war.

After the war, a German lawyer named Hermann Kantorowicz studied the causes of World War I. He found that Germany had a big part in starting the war. He said the White Book was an example, as about 75 percent of its documents were changed.

Translations

The color books were often translated into English. These translations were usually approved by the governments that published them. For example, the Royal Italian Embassy approved the English translation of the Italian Green Book.

The New York Times newspaper even republished the full text of many color books in English. This included the Green Book, British Blue Book, German White Book, Russian Orange Book, Belgian Gray Book, French Yellow Book, and Austrian Red Book.

Specific Color Books

British Blue Book

The British Blue Book is the oldest, dating back to at least 1633. It was a way for England to publish diplomatic letters and reports. It was named for its blue cover. These books were widely used in England in the 1800s.

During World War I, the British Blue Book was the second collection of official documents about the war. It came out just days after the German White Book. It had 159 items and was given to Parliament before August 6, 1914, after Britain declared war on Germany. It later came out in a bigger version with an introduction. Even though it was missing some information, it is considered a valuable source for understanding the crisis.

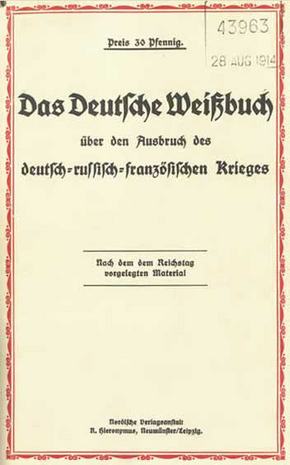

German White Book

The German White Book (German: Das Deutsche Weißbuch) was published by the German government in 1914. It aimed to explain their reasons for World War I. Germany started publishing these official diplomatic documents later than Britain. There was a lot of discussion in Germany about whether it was a good idea to publish them.

The full title was "The German White Book about the outbreak of the German-Russian-French war." An official English translation was published in 1914. The book contained parts of diplomatic papers. These were meant to blame other countries for the war. It had far fewer documents than the British Blue Book. The documents it did include were mostly to support the White Book's story.

Russian Orange Book

The Russian Orange Book came out in mid-August 1914. On September 20, 1914, the New York Times published parts of it. The newspaper said that looking at the Russian Orange Book and the British Blue Book together clearly showed that Germany and Austria were responsible for the war.

Serbian Blue Book

Studying Serbia's role in the war was difficult because the Serbian Blue Book was published late. Some parts of it became available in the mid-1970s.

Belgian Gray Books

The two Belgian Gray Books were published after the Russian Orange Book and Serbian Blue Book. The second one came out in 1915.

French Yellow Book

The French Yellow Book (Livre Jaune) took three months to complete. It had 164 documents and was published on December 1, 1914. Unlike other books that only covered the weeks before the war, the Yellow Book included some documents from 1913. This was done to make Germany look bad by showing their plans for a European war. Germany said some documents in the Yellow Book were not real. But their complaints were mostly ignored. The Yellow Book was often used as a source during the July crisis of 1914.

After the war, it became clear that the Yellow Book was not complete or fully accurate. Historians found new French documents that had not been published before. These showed that the Yellow Book had left out some truths. For example, Yellow Book document #118 showed Russia getting its army ready after Austria did. But in reality, Russia got its army ready first. After a confusing explanation from the French government, people lost trust in the Yellow Book. Historians then avoided using it.

In 1937, Bernadotte E. Schmitt compared the Yellow Book to newly published French documents. She concluded that the Yellow Book "was neither complete nor entirely reliable." She showed how documents were missing or put in the wrong order to confuse people about when events happened. She believed the new documents would not change views much. Germans would still not see France as innocent. But the French would find reasons to justify their actions in July 1914.

In the German White Book, anything that could help Russia's position was removed.

Austrian Red Book

The Austrian Red Book (or Austro-Hungarian Red Book) has a history going back to the 1800s. An 1868 version was printed in London. It included official letters from the time of Emperor Franz Josef. It covered topics like treaties and relations with other countries.

Austria-Hungary was the last of the major powers to publish its documents about the war's start. This happened in February 1915. The book was called: "K. and k. Ministry of Foreign Diplomatic Affairs on the Historical Background of the 1914 War." They also published a smaller, popular version. This Red Book had 69 items and covered the period from June 29 to August 24, 1914.

It's not clear why Austria-Hungary waited over six months to publish their book. For Austria-Hungary, the war was mainly about Austria and Serbia. There were always plenty of documents about it from the very beginning.

Other Color Books

Other countries also used color books, including:

- China—Yellow Book

- Finland—White Book

- Italy—Green Book

- Japan—Gray Book

- Mexican—Orange Book

- Netherlands—Orange Book

- Russian Empire—Orange Book

- Soviet—Red Book

- Spain—Red Book

- United States—Red Book

What People Thought at the Time

World War I

Edmund von Mach wrote a book in 1916 about the official documents related to the start of the European War. He explained color books like this:

In countries with a government elected by the people, it's common for leaders to give "collected documents" to the people's representatives. These documents contain information that helped the government make its foreign policy decisions.

In Great Britain, these documents are often printed on large, loose sheets of white paper, called "White Papers." If the documents are very important, they are later reprinted as small books. These are then called by the color of their cover, like "Blue Books."

When World War I started in 1914, several governments besides Great Britain published collections of documents. These became known by the color of their covers, such as the German "White Book," the French "Yellow Book," and the Russian "Orange Book."

Each government followed its own customs. They published more or less complete collections. In every case, their main goal was to make themselves look good to their own people.

In America, the British Blue Book was the most popular. This was because it came out first and was also very good. Its messages were well written and numerous enough to tell a clear story. The book was well printed and had indexes. It was the best work done by any European government.

The German White Book, however, had few messages. These were only used to support points in a long argument. This kind of presentation is only convincing if you trust the person who wrote it. There's no doubt that the British Papers are better for studying than the German Papers. But even the British Papers are not complete, as many people thought. So, scholars cannot fully rely on them as the final truth.

— Edmund von Mach, Official Diplomatic Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European War (1916)

See also

- British propaganda during World War I

- Causes of World War I

- Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War

- German entry into World War I

- History of propaganda

- History of the United Kingdom during World War I

- Home front during World War I

- Italian propaganda during World War I

- Opposition to World War I

- Propaganda in World War I

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |