British propaganda during World War I facts for kids

During the First World War, countries used something called propaganda to influence what people thought and felt. It was like a way for governments to share their message and get support for the war. British propaganda used many different things, like pictures, books, and movies. They also focused a lot on telling stories about bad things the enemy did, which is called atrocity propaganda. This was to make people angry at Imperial Germany and its allies, the Central Powers.

Contents

How Britain Organized Propaganda

When the war began, different parts of the British government started their own propaganda efforts. But they weren't working together very well. Soon, a new important group was set up at Wellington House. It was led by a man named Charles Masterman. Even with this new group, different agencies still did their own thing. It wasn't until 1918 that all these activities were brought together under one main group, the Ministry of Information.

After the war ended, most of the propaganda groups were closed down. Later, people talked a lot about how Britain used propaganda, especially the stories about enemy cruelty. Some people, like Arthur Ponsonby, showed that many of these stories were either made up or made to sound much worse than they were. This made people suspicious of such stories. Because of this, when Nazi Germany started doing terrible things before World War II, some people found it hard to believe how bad it really was.

In Germany, after the war, some military leaders like Erich Ludendorff said that British propaganda helped cause their defeat. Adolf Hitler agreed with this idea. Later, the Nazis used many of these same British propaganda techniques when they were in power from 1933 to 1945.

Early Propaganda Efforts (1914–1915)

Britain didn't have any special groups for propaganda when the war started. So, they had to quickly figure out how to do it. They set up several groups during the war and tried to make them work together better. By 1918, most of these efforts were handled by the Ministry of Information.

The first propaganda group was created because Germany was already very active in spreading its own messages. Charles Masterman was chosen to lead this new group, which was based at Wellington House in London. After a couple of meetings in September 1914, the war propaganda group started its work. They often worked in secret, and even Parliament didn't know much about what they were doing.

Until 1916, Wellington House was the main British propaganda group. It mostly focused on sending messages to the United States, but it also had sections for other countries. By February 1916, Wellington House had grown a lot, with new departments and more staff.

The group started its propaganda work on September 2, 1914. Masterman invited 25 famous British writers to Wellington House. They talked about the best ways to promote Britain's interests during the war. Many writers agreed to write small books and pamphlets that would share the government's point of view.

Besides Wellington House, the government set up two other groups for propaganda. One was the Neutral Press Committee. Its job was to give information about the war to newspapers in countries that were not fighting. It was led by G. H. Mair. The other was the Foreign Office News Department. This group gave all official statements about British foreign policy to foreign newspapers.

At the beginning of the war, many volunteer groups and individuals also tried to create their own propaganda. Sometimes, this caused problems with Wellington House because their messages weren't always coordinated.

Bringing Propaganda Together (1916)

Because the different groups weren't working well together, all propaganda activities were brought under the Foreign Office after a meeting in 1916. The Neutral Press Committee joined the News Department, and Wellington House was also placed under the Foreign Office's control.

Only Masterman didn't like this change. He was worried that Wellington House would lose its freedom. However, people later started to criticize the Foreign Office's control over propaganda, especially the War Office. When David Lloyd George became prime minister, the propaganda system was changed again.

Propaganda Under Lloyd George (1917)

In January 1917, Lloyd George asked Robert Donald, a newspaper editor, to write a report about the current propaganda setup. Donald's report said that there was still a lack of coordination. However, he did praise Wellington House's work in America.

Right after this report, the government decided to create a separate department just for propaganda. In February 1917, John Buchan was chosen to lead this new group, called the Department of Information. It was located at the Foreign Office. But this new group also faced criticism. Donald suggested even more changes, and other important people like Lord Northcliffe and Lord Burnham supported him. Buchan was temporarily placed under Sir Edward Carson until Donald wrote another report later that year.

Donald's second report again pointed out that there was still no real unity or coordination. This time, even Wellington House was criticized for not being efficient and for how it distributed information. Both Masterman and Buchan said that the investigation behind the report was too limited. Still, more and more people criticized the propaganda system. After Carson left the War Cabinet in 1918, it was decided that a new ministry should be created.

Ministry of Information (1918)

In February 1918, Lloyd George gave Lord Beaverbrook the job of setting up the new Ministry of Information. From March 4, 1918, this ministry took control of all propaganda activities. It was divided into three parts: one for propaganda at home, one for foreign countries, and one for military propaganda. The foreign propaganda part was led by Buchan. Propaganda in military areas was handled by the War Office. Propaganda at home was managed by the National War Aims Committee (NWAC). Another group was set up under Northcliffe to deal with propaganda aimed at enemy countries. This group reported directly to the War Cabinet, not to the Minister of Information.

The new ministry finally brought together all the propaganda efforts, just as Donald's second report had suggested. It worked as an independent group, separate from the Foreign Office.

However, there were still some problems and criticisms. There were tensions between the new Ministry of Information and older ministries like the Foreign Office and the War Office. Many in the government were also worried about the growing power of newspapers, especially since journalists were now in charge of the new propaganda ministry.

In October, Lord Beaverbrook became very sick. His assistant, Arnold Bennett, took over for the last few weeks of the war. After the war ended, the propaganda system was mostly shut down, and control of propaganda went back to the Foreign Office.

How Britain Spread Its Message

British propagandists used many different ways to spread their messages during the war. They always tried to make sure their information seemed believable.

Books and Leaflets

British groups distributed many different types of written propaganda during the war. These included books, small papers called leaflets, official government publications, speeches by ministers, and messages from the King. They were mostly aimed at important people, like journalists and politicians, rather than everyone.

Leaflets were the main type of propaganda in the first years of the war. They were sent to many different foreign countries. These leaflets were serious and factual, like academic papers, and were sent through unofficial ways. By June 1915, Wellington House had sent out 2.5 million propaganda documents in different languages. Eight months later, that number had grown to 7 million.

The production of leaflets was greatly reduced under the Ministry of Information. This was because ideas about the best ways to do propaganda changed, and there was also a shortage of paper.

News Coverage

British propagandists also tried to influence foreign newspapers. They gave information to these papers through the Neutral Press Committee and the Foreign Office. Special telegraph offices were set up in cities like Bucharest, Bilbao, and Amsterdam to help spread information quickly.

To add to this, Wellington House created illustrated newspapers. These were similar to the Illustrated London News and were inspired by how Germany used pictures in its propaganda. They made different language versions, such as America Latina in Spanish, O Espelho in Portuguese, Hesperia in Greek, and Cheng Pao in Chinese.

Movies

British propagandists were slow to use movies as a way to spread their message. Wellington House suggested using films soon after the war started, but the War Office said no. It wasn't until 1915 that Wellington House was allowed to start its plans for film propaganda. A Cinema Committee was formed. This committee made and distributed films to Britain's allies and to neutral countries.

The first important film was Britain Prepared (December 1915). It was shown all over the world. The film used real military footage to show how strong and determined Britain was in the war effort.

In August 1916, Wellington House made the film Battle of the Somme, which was very popular.

Recruitment Posters

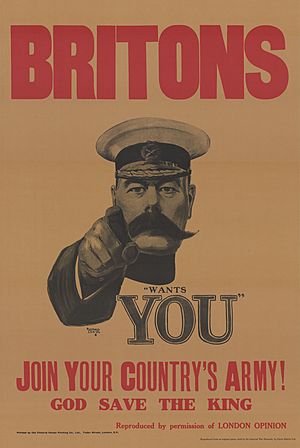

Getting people to join the army was a very important part of propaganda at home until the government started forcing people to join in January 1916. The most common message on recruitment posters was patriotism, which means love for your country. This then changed to asking people to do their "fair share." One of the most famous posters used in the British Army's recruitment campaigns was the "Lord Kitchener Wants You" poster. It showed Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener pointing, with the words "WANTS YOU" below him.

Other ideas used on recruitment posters included the fear of an enemy invasion and stories about terrible things the enemy did. The "Remember Scarborough" campaign is an example of a poster that combined these ideas. It reminded people of the 1914 attack on Scarborough.

Paintings

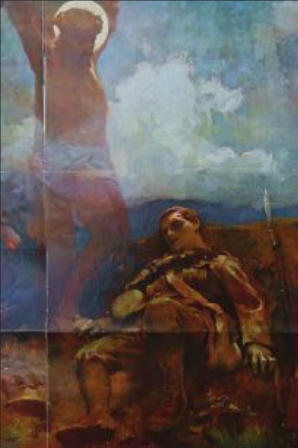

James Clark's 1914 painting, The Great Sacrifice, was printed as a special souvenir in The Graphic newspaper's Christmas issue. The painting showed a young soldier who had died on the battlefield, with a vision of Christ on the Cross above him. Many people immediately loved it. Churches, schools, and mission halls quickly bought copies. One reviewer said that the print "turned railway bookstalls into wayside shrines." Framed copies were hung in churches next to lists of people who had served, and priests gave sermons about the painting's message. The original oil painting was bought by Queen Mary, the wife of King George V. Clark also painted The Bombardment of the Hartlepools (16 December 1914). He designed many war memorials and his painting was used as the basis for several memorial stained glass windows in churches.

Stories of Enemy Cruelty

Atrocity propaganda was used a lot by Britain during the war. It aimed to make people hate the German enemy by sharing details of their cruel actions, whether real or made up. This type of propaganda was most common in 1915. Many of the stories were about Germany's invasion of Belgium, known as the Rape of Belgium. Newspaper stories about "Terrible Vengeance" first used the word "Hun" to describe the Germans because of these stories from Belgium. A constant flow of stories followed, painting the Germans as destructive and barbaric. However, many of the reported cruel acts were made to sound worse or were completely false. The German Kaiser (emperor) often appeared in propaganda from the Allied countries. His image changed from a polite gentleman to a dangerous troublemaker. During the war, he became the symbol of German aggression. By 1919, British newspapers were even calling for him to be executed. He died in exile in 1941. By then, his former enemies had softened their criticism and instead focused their hatred on Hitler's terrible actions.

The Bryce Report

One of the most widely shared documents of atrocity propaganda during the war was the Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages, also known as the Bryce Report, from May 1915.

This report was based on statements from 1,200 witnesses. It described how German soldiers supposedly systematically murdered Belgians during their invasion of Belgium. The report was published by a group of lawyers and historians, led by a respected former ambassador, Lord Bryce. It had a big impact in both Britain and America and was on the front page of major newspapers. It was also translated into 30 languages to be shared in Allied and neutral countries. Its impact in America was even greater because it was published soon after the sinking of the Lusitania ship. In response to this report, Germany published its own counter-propaganda, called the 'White Book'. This book described cruel acts that Belgian civilians supposedly committed against German soldiers. However, Germany's report didn't have much impact, except in a few German-language publications. In fact, some people saw it as Germany admitting guilt.

Other publications about the violation of Belgium's neutrality were later shared in neutral countries. For example, Wellington House sent out a pamphlet called Belgium and Germany: Texts and Documents in 1915. It was written by the Belgian Foreign Minister Davignon and included details of alleged cruel acts.

Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell was a nurse with the International Red Cross in Brussels. She was secretly part of a British Intelligence network that helped Allied prisoners of war and Belgian men of military age escape. Because helping enemy soldiers went against her protection as a Red Cross nurse, Cavell was put on trial under German military law. She was found guilty and executed by a firing squad in 1915. However, the story was reported as the murder of an innocent nurse who was helping refugees. This made her a symbol of German cruelty in Allied propaganda.

The Lusitania Medal

British propagandists used the sinking of the Lusitania ship as atrocity propaganda. This was because a German artist named Karl Goetz privately made a special medal a year later to remember the sinking. The British Foreign Office got a copy of this medal and sent pictures of it to America. Later, to increase anti-German feelings, Wellington House made a replica of the medal in a box. It came with a leaflet that explained how barbaric Germany was. Hundreds of thousands of these replicas were made in total, but Goetz's original medal had fewer than 500 copies.

See also

- History of the United Kingdom during World War I

- John R. Rathom

- Wellington House

- British propaganda during World War II

- Propaganda and censorship in Italy during the First World War

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |