Compulsory figures facts for kids

Compulsory figures, also called school figures, were once a very important part of figure skating. In fact, they gave the sport its name! These figures were special circular patterns that skaters drew on the ice. They showed how skilled a skater was at making smooth, even turns on perfect circles.

For about 50 years, until 1947, compulsory figures made up 60% of a skater's total score in most competitions. They were a huge part of the sport. However, their importance slowly decreased. Finally, in 1990, the International Skating Union (ISU) decided to remove them from competitions.

Learning and practicing these figures taught skaters great discipline and control. Many people in figure skating believed they were essential for teaching basic skills. Skaters spent many hours training to perform them perfectly. Judging these figures could even take up to eight hours during a competition!

Contents

What Are Compulsory Figures?

Compulsory figures were all about drawing perfect patterns on the ice. Skaters were judged on how smooth and accurate their tracings were. The basic shape for all figures was the circle.

Other important parts of these figures included curves, changing feet, changing the edge of the skate, and different turns. Skaters had to draw very precise circles while doing tricky turns and using different edges of their blades.

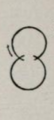

A simple example is the "figure eight," made by connecting two circles. Other figures included the three turn, the counter turn, the rocker turn, the bracket turn, and the loop.

Why Figures Still Matter

Even though most skaters don't practice compulsory figures anymore, some still believe they are very helpful. Many coaches think figures give skaters an advantage. They help develop good body alignment, core strength, control, and discipline.

Since 2015, the World Figure Sport Society has held special events and competitions for compulsory figures. These events are supported by the Ice Skating Institute. This shows that figures are still valued by some in the skating world.

The Story of Compulsory Figures

How Skating Began

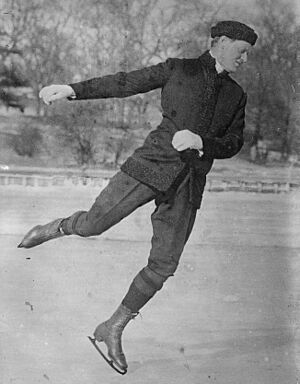

Tracing patterns on the ice is the oldest way people enjoyed figure skating. For the first 200 years, it was mostly a fun activity for men. Skating together, where two skaters made patterns around a central point, was also very important. This led to modern ice dancing, pair skating, and synchronized skating.

In 1772, Robert Jones wrote one of the first books about skating. It showed five advanced figures. Early skating clubs, like the Edinburgh Skating Club (one of the oldest!), even made new members pass tests on these figures. The London Skating Club, started in 1830, also had similar tests.

French skaters, inspired by ballet, focused on making figures look artistic and graceful. Jean Garcin, a French skater, wrote a book in 1813. It showed over 30 figures, including many "figure eight" patterns still used today.

By the 1850s, key figures like the figure eight, three turn, and Q figure were well-known. These became the foundation of figure skating. In 1869, two skaters from the London Skating Club wrote a book describing many figures. These included the three turn, bracket, rocker, Mohawk, and loop. Some figures, like the Mohawk and grapevine, likely started in North America.

In 1868, the American Skating Congress (which later became U.S. Figure Skating) started using specific moves for competitions. As mentioned, compulsory figures were 60% of the score until 1947. Early competitions also included "special figures" and free skating.

The first international figure skating competition was in Vienna in 1882. Skaters had to perform 23 compulsory figures. They also did a four-minute free skating program and "special figures" to show off advanced skills.

Compulsory figures remained a big part of figure skating until the 1930s and 1940s. The first European Championships in 1891 only had compulsory figures. In 1896, the new International Skating Union (ISU) held the first World Championships. Skaters performed six compulsory moves and a free skating program. The figures were worth 60% of their total scores.

"Special figures" were not part of the World Championships. However, they were a separate event in other competitions, like the Olympics in 1908. Early Olympic sports valued amateurism. This meant athletes could not be paid for their sport. This made it hard for many to practice figures for hours. Practicing figures needed a lot of time and access to private rinks.

In 1897, the ISU adopted a list of 41 school figures. These figures got harder and harder. They were the standard for tests and competitions worldwide until 1990. After World War II, more countries sent skaters to international events. So, the ISU reduced the number of figures to a maximum of six. This was because judging them all took too much time. The first guide for judges of compulsory figures was published by the ISU in 1961.

Figures Disappear and Return

Compulsory figures were removed from international single skating competitions in 1990. This happened partly because of judging issues and the rise of figure skating on television. The U.S. was the last country to include figures in its competitions, stopping in 1999.

Removing figures meant skaters focused more on the free skating part of the sport. It also led to younger girls often dominating the sport. Most skaters stopped training with figures. However, many coaches kept teaching them. They believed figures taught basic skating skills. They also gave skaters an advantage in developing alignment, core strength, body control, and discipline.

A new interest in compulsory figures began in 2015. The first World Figure Championships took place in Lake Placid, New York. By 2023, nine championships had been held. Judging was done "blind," meaning judges didn't know which skater performed which figure. Karen Courtland Kelly, an Olympian and figures expert, helped bring figures back. She founded the World Figure Sport Society (WFSS) and organized its championships. Many skaters, including U.S. Olympian Debi Thomas, supported this revival. Debi Thomas even competed in the 2023 Championships.

How Skaters Performed Figures

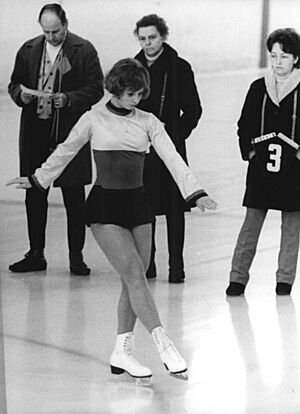

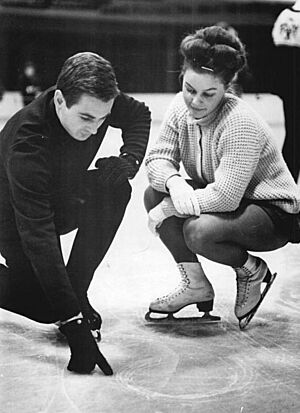

Compulsory figures were sometimes called "patch." This referred to the small area of ice given to each skater for practice. Figure skating experts saw figures as a way to build skills for elite skaters. They were like musical scales for musicians. Figures helped skaters develop the smooth technique needed for free skating programs. Some even called compulsory figures "the slow-sports movement" or "yoga on ice."

Skaters had to trace these circles using one foot at a time. They showed their amazing control, balance, flow, and edge work. This created accurate and clean patterns on the ice. The ISU's figures in 1897 involved two or three connected circles. Skaters completed one, one and a half, or two full circles on each foot. Some figures included turns or loops.

The patterns left on the ice were the main focus. Judges looked at the quality of the figures. They also watched the skater's form, posture, and speed. Skaters had to control their skate blade's edges precisely. They leaned in or out, moving forward or backward. They used one foot while balancing the other to stay on course. Then, they repeated everything five more times!

Olympic champion Debi Thomas said performing figures took "incredible strength and control." She explained, "You are literally using every single muscle in your body. It looks slow and easy, but it's not … but if you lay out a great figure, it’s an amazing feeling."

The best figures had tracings perfectly on top of each other. Their edges were placed exactly, and turns lined up perfectly. Even a tiny mistake in balance could cause errors. American champion Irving Brokaw believed good form was key. Skaters needed to find a comfortable and natural position. He advised skaters not to look down at their tracings. He also suggested not using arms too much for balance. Brokaw wanted skaters to stay upright and avoid bending over. He also thought the "balance leg" (the one not on the ice) was just as important. It helped control the tracing leg.

Skaters who were good at figures practiced for hours. They developed amazing body control. They learned how small changes in balance affected the tracings. Many skaters found figures calming and rewarding. Sports writer Christie Sausa said figure training "helps create better skaters and instills discipline." It can be practiced by skaters of all ages. In 1983, a German magazine said figures limited skaters' creativity. This was because figures hadn't changed much in 100 years.

Figure Elements

All compulsory figures had these parts: circles, curves, change of foot, change of edge, and turns. The circle was the base of every figure. Skaters had to draw precise circles while doing difficult turns and edges. Most figures used specific one-foot turns. Each figure had two or three connected circles. Each circle's diameter was about three times the skater's height.

Curves were parts of circles. They had to be smooth and continuous, with no wobbles. Brokaw said curves needed to be done on all four edges of the skate, both forwards and backwards. He believed controlling these circles built strength and power. Performing these figures, changes of edges, and turns made up the art of skating.

A change of foot happened when a skater shifted weight from one foot to the other. This was allowed in a specific zone. A change of edge happened where the figure's main lines crossed. It had to be smooth and short, not S-shaped. Turns were skated with a single clean edge before and after the turn. There should be no scrapes or illegal edge changes. The turns had to be symmetrical.

The simple "figure eight" connected two circles. Each circle was about three times the skater's height. It had four types: inside edges, outside edges, backward, and forward. Adding a turn in the middle of each circle made it harder. Other figures included three-lobed shapes with a counter turn or a rocker turn. These turns had to be symmetrical and clean. Brackets, like threes, were skated on a circle.

Skaters also performed smaller figures called loops. A loop's circular shape was about the skater's height. They had to be perfectly smooth, with no scrapes. The entry and exit points of the loop had to be on the figure's main line. The Q figure started on the skater's outside edge. It could also begin on any of the four edges. Altered Q figures sometimes looked like a serpentine line with a three turn.

The goal of figures was to draw an exact shape on the ice. Skaters focused on the depth of the turn, the quality of the edges, and the overall shape. There were three types of three turns: the standard three, the double three, and the paragraph double three. The paragraph double three was very difficult. It involved tracing two circles with two turns on each circle, all on one foot from one push-off. This required perfect symmetry and clean edges.

Judging Figures

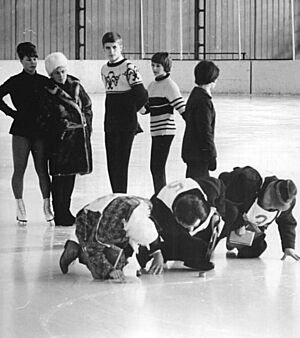

Some people compared judging compulsory figures to the work of forensic scientists. After skaters finished tracing, judges carefully examined the circles. This process was repeated two more times. Randy Harvey noted that figures took five hours at U.S. National Championships. They took eight hours at World Championships. At the 1983 European Championships, the figures segment lasted six hours.

Louise Radnofsky said watching figures could be "very boring." She also mentioned that the results were usually only visible to skaters and judges. Then, the ice was swept clean.

The ISU published the first judges' guide for compulsory figure competitions in 1961. Skaters were judged on how easily and smoothly they moved. Judges also looked at the accuracy of their body shapes. Most importantly, they checked the accuracy of the patterns traced on the ice.

Judges looked for many things. These included scrapes, double tracks (where both edges of the blade touched the ice), and deviations from a perfect circle. They also checked how closely repeated tracings followed each other. How well loops lined up was also important.

Judges started with a perfect score of 6.0. They then took away points for different errors. For example, a small mistake might be a 0.1 deduction. A badly shaped loop might be a 0.5 deduction. Some errors were hard to see in the final tracing. Poor lighting made it even harder. Sometimes, errors were only visible while the skater was performing.