Cornelius Hill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cornelius Hill

|

|

|---|---|

The Rev. Cornelius Hill

|

|

| Born | November 13, 1834 |

| Died | January 25, 1907 (aged 72) |

Cornelius Hill (born November 13, 1834 – died January 25, 1907) was also known as Onangwatgo, which means “Big Medicine.” He was the last traditional chief of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. Chief Hill worked hard to protect his people's lands and rights. He did this by working with the United States government on various agreements, called treaties. He was a member of the Episcopal Church his whole life. At age 69, he became a priest in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. He served his community until just before he passed away.

The Oneida people are one of the five original tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. They sided with the Americans during the American Revolutionary War. Later, white settlers started moving into their lands. Many settlers confused the Oneida with other tribes. Because of this pressure, the Oneida began moving to Wisconsin around 1821. They negotiated with the Ho-Chunk and Menominee tribes for new lands. Many Oneida people became Christians through missionaries from the Episcopal and Methodist Churches. In 1825, tribal members built a log church near the Fox River in Wisconsin. They named it the Hobart Chapel.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Cornelius Hill was born on tribal lands in Wisconsin. He was baptized by Bishop Jackson Kemper. In 1843, when he was ten years old, Cornelius and two other boys went to Nashotah House. This was a new school where they learned English and received an education for five years.

A Leader for His People

As a teenager, Cornelius Hill became a chief of his Bear Clan. This happened at a meeting of Oneida people from New York, Canada, and Wisconsin. When he was 18, he was given the important job of sharing money among his people. This money, called "annuity money," came from their service in the Revolutionary War. Later, he was in charge of counting all the tribal members. The number of Oneida people in Wisconsin actually doubled during his 50 years of leadership!

Chief Hill traveled many times to Albany, New York and Washington, D.C.. He went there to speak up for his people and protect their rights.

Protecting Oneida Lands

White settlers were moving into Wisconsin and wanted the tribal lands. These lands were owned by the whole tribe under a treaty from 1838. Chief Daniel Bread had negotiated this treaty. However, by the time he died in 1873, he thought the tribe would have to divide their lands among individuals.

The next year, Chief Hill wrote a request to New York's government. He was concerned about people interfering with the Oneida's fishing rights. These rights were protected by older treaties. Losing these rights caused great hardship for Oneida members still in New York.

There was also an "Indian Agent" who was supposed to help the tribe. But this agent stopped them from selling wood products to support themselves. This happened during a time when their crops failed. Chief Hill and a missionary named Rev. Edward A. Goodnough believed the agent wanted the tribe to sell their lands. They worked to get this agent removed from his position.

Chief Hill also helped tribal members learn new ways to farm. He helped them get new farming machines. Oneida women also made baskets and beadwork to sell. After 1900, they learned to make lace to earn money.

Fighting for Land Rights

Despite their efforts, the federal government began dividing the tribe's land in Wisconsin. This started in 1892 under a law called the Dawes Act. This law gave pieces of land to individual tribal members. They were supposed to be able to sell this land after 25 years. However, dishonest people often tried to trick tribal members out of their land.

Throughout his life, Chief Hill fought against this division of tribal property. He also fought against government attempts to move his people further west. In 1893, Chief Hill and Rev. Solomon S. Burleson worked with the federal government. They successfully secured a hospital and a boarding school for the reservation. The next year, the Sisters of the Holy Nativity sent nuns to work as nurses and teachers there.

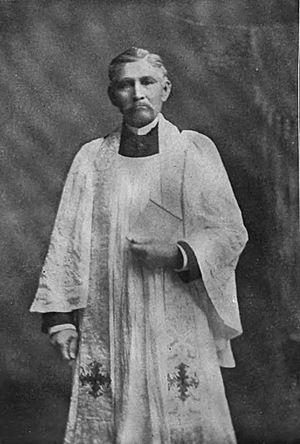

Becoming a Priest

For many years, Cornelius Hill played the organ and translated for Episcopal church services. He also served as his tribe's leader and represented them at church meetings. He believed becoming a priest would give him more authority among white people. He also thought it would help him connect the Oneida culture with the wider world.

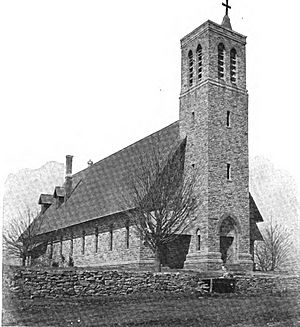

Since 1870, church members had volunteered to work at a stone quarry once a week. They did this to get stone for a new church building. In 1886, they laid the first stone for a new stone church. They named it the Church of the Holy Apostles. It was built to replace their old, small wooden chapel.

On June 27, 1895, Bishop Charles C. Grafton made Hill a deacon. This was a sad day for Hill, though, because his baby son had died from an illness and was buried that same afternoon. Also, his friend Rev. Burleson died in February 1897. This was months before the new church was officially opened.

On June 24, 1903, Bishop Grafton ordained Hill as a priest. He was the first Oneida person to become a priest. During the ceremony, Hill repeated his promises in his native language. The Oneida reservation also had a Methodist church and a Catholic chapel.

Family Life

When Cornelius Hill became a priest, he was 69 years old. His wife had given birth to 8 children. She had not learned English. Several of their children went to the Hampton Indian School after attending the reservation's school.

Death and Lasting Impact

Cornelius Hill became sick shortly before Christmas and passed away on January 25, 1907. His funeral was held at the Church of the Holy Apostles. About 800 people attended. He was buried in the church graveyard with other tribal members and missionaries.

On July 17, 1920, a lightning strike caused a fire that destroyed the stone church. But it was rebuilt with a similar design. The Oneida people continued to remember Chief Hill's wisdom and his good deeds. They shared stories about him with historians during the Great Depression. By 1920, only a small part of the reservation land was still owned by tribal members. However, a law called the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934 began to reverse this policy.

Images for kids