Daniel Bread facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel Bread

|

|

|---|---|

| Tekaya-tilu, Tega-wir-tiron ("Learning Body") | |

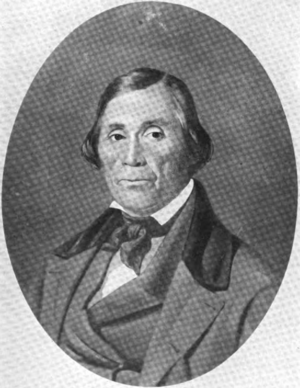

Daniel Bread, Chief of the Oneida, 1831

|

|

| Oneida leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 27, 1800 Oneida Castle, New York |

| Died | July 23, 1873 |

| Cause of death | Bilious fever |

| Political party | First Christian |

| Known for | principal chief of the Oneida people |

Daniel Bread (born March 27, 1800, died July 23, 1873) was an important leader of the Oneida tribe. He helped his tribe keep their traditions alive while moving from New York to Wisconsin. At that time, Wisconsin was known as Michigan Territory.

Even though he wasn't born into the role, many called him a "principal chief" or "head chief." Daniel Bread was practical. He found ways to work with both his tribe's leaders and government officials. He helped the Oneida keep their rights and land. He also played a big part in changing an old Iroquois ceremony. It became a July 4 celebration that honored the Oneida's friendship with George Washington during the American Revolution. When he was 14, Daniel Bread helped defend Sackets Harbor, New York during the Battle of Big Sandy Creek.

Contents

Early Life of Daniel Bread

Daniel Bread was the son of Dinah Bread and an Oneida man named Williams. His biological father died, and he was later renamed after his stepfather, Daniel Bread. He had at least one sister.

We don't know much about Daniel Bread's early years. But historian Laurence M. Hauptman says he went to a mission school. This school was on the Oneida reservation. There, he learned to read and write English. He also studied math and the Christian catechism. Daniel Bread probably learned a lot from stories told by older Oneida leaders too. He saw how Skenandoa, a leader, lost influence. Skenandoa had signed away much of the Oneida land in the 1780s and 1790s. During Daniel Bread's youth, his tribe faced diseases like yellow fever and tuberculosis.

Oneida Tribe Moves to Wisconsin

In 1817, a Canadian clergyman named Eleazer Williams became a missionary to the Oneida. He suggested that the Iroquois tribes move from New York to Michigan Territory. Williams led groups to Green Bay to make agreements. They met with the Menominee and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribes. They secured land along Duck Creek and in the Fox River Valley.

Daniel Bread worked hard during this time. He helped unite the Oneida community, which was very divided. He wanted to prevent the Oneidas from having to move again. Historians say he was the most important person. He helped manage the entire move to Michigan Territory.

Meeting with U.S. Leaders

In 1831, Daniel Bread and other Native American leaders went to Washington. They wanted to challenge changes to Oneida lands. These changes came from the 1827 Treaty of Butte Morts and the 1831 Treaty of Washington. In Washington, they met with Lewis Cass, who was the Secretary of War.

They also met with President Andrew Jackson at the White House. Daniel Bread explained that the 1831 treaty did not give the Oneida enough good land. President Jackson agreed with Daniel Bread's idea. He accepted a plan to trade lands for better, "more fertile" lands. These new lands were in the southern part of Menominee Territory.

Working for Tribal Rights

In the 1830s, Daniel Bread kept working to unite his tribe. He also found ways to compromise between tribal and federal plans. In 1834, another Oneida chief, Jacob Cornelius, arrived. He became a political rival to Daniel Bread.

Daniel Bread's group (the First Christian party) and Jacob Cornelius's group (the Orchard Party) worked separately. They had their own chiefs, churches, schools, and lacrosse teams. But the two leaders joined forces for important issues. They argued for federal payments owed from the Treaty of Canadaigua and the Treaty of Buffalo Creek. They also sought state relief funds from New York State. In 1836, the two men signed the Oneida Treaty of Washington. This treaty gave the Oneida a separate 65,420-acre piece of land.

Daniel Bread as Principal Chief

Daniel Bread became the main chief of the Wisconsin Oneidas in 1832. He was an active member of the Hobart Church (Episcopal). He sang in the choir and read during services. He also became successful in business. He ran a blacksmith shop, a shoe shop, and a merchandise store. He lived in a large, three-story house.

Daniel Bread led the tribe to change an old Iroquois condolence ceremony. It became an annual celebration of Independence Day. Oneida chiefs invited white guests to this event. The day included speeches by Oneida chiefs and lacrosse games. There were also social dances, fireworks, and meals. Both the Methodist and Episcopal churches served food. The annual Oneida pow-wow is still celebrated on July 4 today.

Challenges and Later Life

Some people criticized Daniel Bread. They thought he was too friendly with white people. This was because he supported missionary schools and adapting to new ways. He also became a U.S. citizen. Some even accused him of using his power to get money from the government.

After the American Civil War, Daniel Bread helped Native American families. He helped them apply for pensions. He also aided widows and orphans. In 1867, he became the guardian for a teenager named Sallie Anthony. Her father had died while serving in the military.

By late 1869, Chief Bread's leadership had weakened. Historians say this was because he lost influence with federal Indian agents. He also lost influence with the Episcopal Church in Wisconsin. According to a federal agent, Daniel Bread had stopped attending church. He had also "deserted his party." Daniel Bread's friend, Bishop Jackson Kemper, died in 1870. Another leader, Edward A. Goodnough, became more powerful in Oneida Nation politics. In 1865, Daniel Bread and Chief Adam Swamp had asked Washington to remove Goodnough.

Daniel Bread also tried again to work with Chief Jacob Cornelius. They wanted to protect the tribe's timber resources. Meanwhile, a hereditary Oneida chief, Cornelius Hill, was gaining power. Cornelius Hill was allied with Goodnough.

Daniel Bread died on July 23, 1873, from "bilious fever." His granddaughter, Laura Cornelius Kellogg, later founded the Society of American Indians. She continued to speak up for the Oneida and Haudenosaunee people.