Laura Cornelius Kellogg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

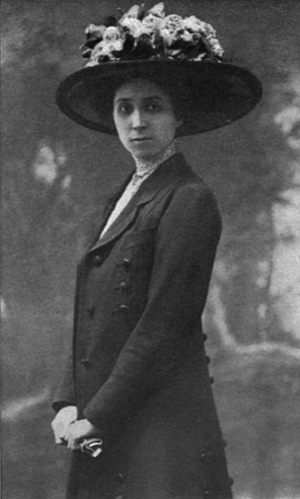

Laura Cornelius Kellogg

|

|

|---|---|

Laura Cornelius Kellogg

|

|

| Born | September 10, 1880 |

| Died | 1947 (aged 66–67) |

| Other names | Minnie Kellogg |

| Occupation | Native American activist |

Laura Cornelius Kellogg (also known as "Minnie" or "Wynnogene") was an important Oneida leader, writer, speaker, and activist. She was born on September 10, 1880, and passed away in 1947.

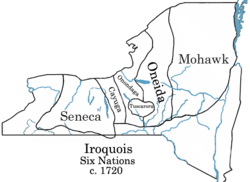

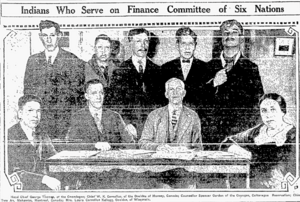

Kellogg came from a family of respected Oneida leaders. She helped start the Society of American Indians. She strongly supported the Six Nations of the Iroquois people. She wanted them to have their own land and be able to govern themselves. People often called her "Indian Princess Wynnogene." She spoke for the Oneida and Haudenosaunee people around the world.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Kellogg and her husband, Orrin J. Kellogg, worked on land claims. They wanted to get land back for the Six Nations people in New York. Kellogg also created the "Lolomi Plan." This plan was a new idea for Native American communities. It focused on self-sufficiency and working together. It was an alternative to the Bureau of Indian Affairs controlling everything. Historian Laurence Hauptman said Kellogg helped the Iroquois become strong activists in the 20th century.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Laura Cornelius Kellogg was born on the Oneida Indian Reservation. This was near Green Bay, Wisconsin. She was one of five children of Adam Poe and Celicia Bread Cornelius. Her family had many important Native American leaders. This made her very proud of her Oneida heritage.

Her grandfather, John Cornelius, was an Oneida chief. Her other grandfather, Chief Daniel Bread, helped his people find land. This was after the Oneidas were forced to leave New York. Kellogg was also related to Elijah Skenandore. He was a well-known Oneida speaker.

Unlike many Native American children then, Laura did not go to distant boarding schools. She attended Grafton Hall, a private school in Wisconsin. It was close to her home. She graduated with honors in 1898. Her graduation essay compared the Iroquois Confederacy to the ancient Roman Empire. This showed her pride in her Iroquois background.

After graduating, she traveled in Europe for two years. She then studied at several universities. These included Stanford, Barnard College, Columbia, Cornell, and the University of Wisconsin. Even though she didn't finish at these schools, historians say she was one of the best-educated Native American women of her time.

Teaching and Early Activism

"Minnie," as her friends called her, taught for a short time. She taught at the Oneida Indian Boarding School. She also taught at the Sherman Institute in California. In 1903, a group of Cupeño Indians were forced to leave their homes. Kellogg helped persuade them not to fight the move. California newspapers called her "An Indian Heroine." They said she prevented an uprising.

That year, she published a poem called "A Tribute to the Future of My Race." It talked about the relationship between Europeans and Native people. She wrote, "Every human heart is human." She hoped for a good future for her people.

Princess Wynnogene and Global Voice

Kellogg became a voice for the Oneidas and the Six Nations of the Iroquois. She spoke on national and international stages. In 1908, she traveled to Europe for two years. She made a big impression in England. Newspapers called her "Princess Neoskalita" and "The Indian Joan of Arc." Later, she was known as "Indian Princess Wynnogene."

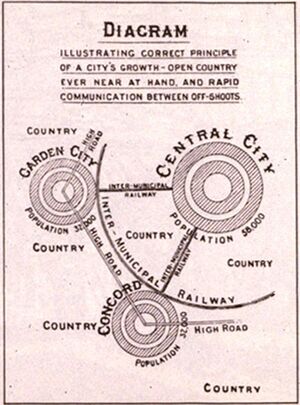

She became interested in the Garden city movement in Europe. This was a way of planning cities with green spaces. She imagined using this idea for Native American reservations. She wanted to help the Oneida people become self-sufficient. She worked towards these goals for the rest of her life.

By 1911, newspapers compared Kellogg to Booker T. Washington. Both called for self-help for their people. As a founder of the Society of American Indians, Kellogg pushed for Native American independence. Her ideas were not always popular. But she found support among the Iroquois. The New York Tribune called her a scholar and a social worker. They said she had "rare intellectual gifts."

In 1919, Kellogg spoke to the League of Nations. She asked for justice for Native Americans. She pointed out that America helped other nations. Yet, Native Americans in their own country still suffered.

Kellogg also supported women's right to vote. She said Iroquois women had equal power with men. This was common among the Iroquois. Clan Mothers decided how land was used. They also organized women to grow food for community events.

Laura and Orrin Kellogg

On April 22, 1912, Laura Cornelius married Orrin J. Kellogg. He was a lawyer with some Seneca heritage. Orrin supported Laura's work.

After their marriage, some people questioned Laura's loyalty to the Oneida tribe. There were claims that she used other people's money for her projects. These projects were sometimes seen as risky. Because of these claims, both Kelloggs were accused of misusing funds. The accusations against them were eventually dropped. However, Laura was removed from the Society of American Indians. She felt this was a great injustice.

Despite this, Kellogg's reputation was not completely ruined. After she wrote her book, Our Democracy and the American Indian, she was again seen as a "leading crusader for Indian rights."

Kellogg's Ideas for Native Americans

Kellogg believed in the importance of a strong "American Indian" identity. She valued the traditional knowledge of elders. In 1911, she said that old Indians who never went to school were often more educated. She meant they had wisdom that young Indians with book knowledge might lack. She saw herself as an "old Indian adjusted to new conditions."

She criticized shows like Buffalo Bill Cody's for showing stereotypes of Native people. She wanted Indian children to learn from their elders and reservations. She believed that not everything done by white society should be copied. She pointed out problems like child labor in cities.

Kellogg was a strong critic of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She felt their schools broke the spirit of Native children. She said her own success came from avoiding those schools. She believed Native education should include traditional practices. She also warned against too much focus on money. She thought the Bureau of Indian Affairs should protect Native people. But she wanted it to be a protector, not a controller. Her strong opinions led to powerful enemies. She faced false accusations and arrests several times.

Kellogg wanted the Haudenosaunee people to reunite. She wanted them to govern themselves and reclaim their lands. Her "Lolomi Plan" was a vision for reservations. It was inspired by the Garden city movement and successful Mormon communities. For over 20 years, she worked on land claims for the Oneida and Six Nations. She also tried to create Lolomi communities.

Society of American Indians

Laura Cornelius Kellogg was a founding member of the Society of American Indians. This group was the first national organization for Native American rights run by Native Americans. It promoted unity among all Native American tribes. The Society brought together a new generation of Native American leaders. These were professionals like doctors, lawyers, and teachers. They believed in progress through education. The Society held conferences and published a journal. It fought for Native American citizenship and access to courts. It was a forerunner of groups like the National Congress of American Indians.

In 1911, Kellogg and five other Native American intellectuals met. They planned the Society's formation. Kellogg hosted a meeting at her home to draft the group's purpose. Her brother, Chester Poe Cornelius, an Oneida attorney, was also there.

At the Society's first meeting in October 1911, Kellogg declared, "I am not the new Indian; I am the old Indian adjusted to new conditions." She presented her "Industrial Organization for the Indian" paper. She suggested turning reservations into self-governing "garden cities." These would have "protected autonomy" and work with the local economy. Many Society members were unsure about her idea. They wanted to get rid of the Bureau of Indian Affairs completely. But Kellogg found support among the Oneida and other tribes.

Kellogg's last conference with the Society was in 1913. She and her husband were accused of misusing funds. They were arrested but later found innocent. Kellogg believed this was a setup by the Indian Bureau. After this, she was removed from the Society. She never forgave them for this "injustice."

The Lolomi Plan for Community Life

Kellogg's Lolomi Plan was based on the Garden city movement. This idea, started in England, aimed to create planned communities. These communities would have homes, businesses, and farms. Kellogg saw how this model could help Native American reservations. She wanted to create "Oneida economic self-sufficiency and tribal self-governance."

The Lolomi plan aimed to protect Native Americans from people who might cheat them. A federal group would manage tribal assets. Native Americans would be part of a cooperative group. Each person would have one vote. Their property would be used for education, health, and business.

The plan aimed for self-governing Native communities. It also included healthcare and recreation centers. Kellogg believed that communities of people with similar backgrounds would work best. She thought Native communities could solve problems better because of their shared culture.

In 1911, Kellogg traveled to reservations to promote her idea. Many important people showed interest. She presented her plan at the Society of American Indians conference. She suggested "industrial villages" with "protected autonomy." These villages would use local skills and needs. This way, Native Americans could use good parts of modern society. They could also avoid problems like factories and city crowding.

In 1914, the Kelloggs moved to Washington, D.C. They wanted to lobby for better laws for Native Americans. Kellogg worked for the rights of many tribes. Her strong activism sometimes led to trouble. She was arrested in Oklahoma in 1913 and Colorado in 1916.

In 1916, Kellogg spoke to Congress. She said the Bureau of Indian Affairs was corrupt. She supported a bill to replace it with a commission. This commission would be controlled by Congress and include Native American leaders.

The Lolomi Plan was inspired by Mormon communities and the Garden City movement. Lolomi villages would be outside the Bureau's control. They would focus on outdoor activities. Industries would fit local needs and skills. Kellogg wrote, "We believe the greatest economy in the world is to be just to all men."

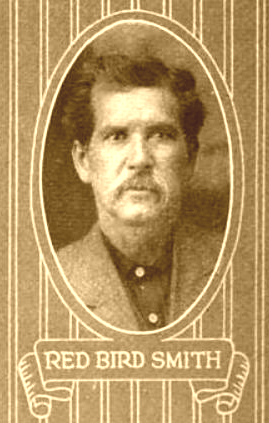

In 1920, Kellogg published her book, Our Democracy and the American Indian. It explained her Lolomi Plan. "Lolomi" means "perfect goodness be upon you" in the Hopi language. She dedicated her book to Chief Redbird Smith. He was a spiritual leader who accepted the Lolomi plan.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Kellogg worked to achieve her Lolomi vision. She tried to buy the Oneida Indian Boarding School. She advised Chief Redbird Smith. She also worked on land claims for the Oneida and Six Nations.

Oneida Cherry Garden City

In 1919, the Bureau of Indian Affairs closed the Oneida Boarding School. Kellogg saw this as a chance to start her Lolomi plan. The school was built on 80 acres in Oneida, Wisconsin. Kellogg argued the school should stay open for Oneida children. She proposed using it as an education and industrial center.

She called her plan for the Oneida "Cherry Garden City." The Oneida homeland was good for growing cherries. She suggested building a canning factory to help the economy. Kellogg wanted the school to teach traditional Oneida culture. The Bureau approved her plan. She tried to get loans from 1919 to 1924. But disagreements within the Oneida community stopped her. The property was sold in 1924 to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Green Bay. Kellogg continued to challenge this sale. Today, the former school site is the Norbert Hill Center. It belongs to the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin.

Keetoowah Nighthawk Society

From 1914 to 1923, Kellogg and her brother Chester worked with the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society. This was a traditional Cherokee group in Oklahoma. They secretly practiced old Cherokee ceremonies. They resisted efforts to make them give up their culture.

Chief Redbird Smith invited Minnie and Chester to help with a Lolomi Plan. Minnie was given the Cherokee name "Egahtahyen" (meaning "Dawn"). She was given power to act for the community. Chester became the spokesperson for the Society. He worked to get the Keetoowah Society a reservation. In 1916, a bill was introduced in Congress to help them. But it did not pass.

In 1917, Chester continued the Lolomi plan. They bought Black Angus cattle from Wisconsin. Many people moved to a new community near Gore, Oklahoma. The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society trusted Chester greatly. He was educated and from the east, which was sacred. He helped them rebuild their old tribal organization.

Chief Redbird Smith passed away in 1918. His son, Sam Smith, became chief. Chester continued as their legal counsel. They started a bank in Gore, with Chester as president.

In 1920, Minnie Kellogg's book was dedicated to Chief Redbird Smith. It honored him for preserving his people. In 1921, many Cherokees moved to create a traditional community.

By 1923, the Lolomi plan was moving forward. Chester hoped the Keetoowah would work for the common good. However, the bank in Gore failed. The cattle were taken, and people lost their land. This happened during a tough economic time after World War I. George Smith, Redbird Smith's son, said Chester was smart. But white people were against him, and they had bad luck. After the plan failed, some Keetoowahs felt Chester had cheated them. He was dismissed as spokesman. But he continued to be a chief for the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin.

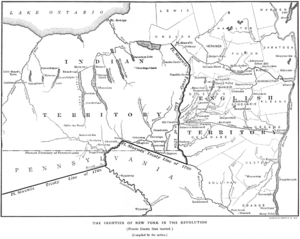

New York Land Claims

The Dawes Act of 1887 greatly reduced the Oneida's land in Wisconsin. The New York Oneida had lost most of their land earlier. Many Oneidas were forced to move from New York in the 1820s and 1830s. Some went to Canada, some to Wisconsin, and some stayed in New York. Treaties had shrunk the Oneida land to only 32 acres.

Six Nations Land Claims

The year 1922 was very important for Kellogg. Her clan mother passed away. After this, Kellogg decided to focus on her tribe's traditions. She worked on two main issues: following Six Nations Laws and advancing land claims.

Also in 1922, a court ruling helped Native Americans. It said New York state courts could not take Indian property without federal consent. This decision, U.S. v. Boylan, returned 32 acres of land to the Oneida. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this ruling.

In March 1922, the Everett Report was presented. This report studied the status of Native Americans in New York. It concluded that the Six Nations Iroquois were owed 6 million acres in New York. This was because their land was taken illegally after the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The state government rejected this report. But the court decision and the Everett Report gave Kellogg hope. She believed they could reclaim Oneida and Six Nations lands.

In October 1922, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin announced they would claim 6 million acres. This land was valued at $2 billion. Kellogg was chosen to raise money for this effort. She and her husband set up headquarters in Onondaga, New York. They spoke in Native communities to gather support and funds.

Kellogg traveled to raise money for the land claims. Her followers were known as the "Kellogg Party." They collected money from Iroquois people in many places. They said the money would be used to claim land in New York and Pennsylvania. But the money was not used for this purpose. Many Native Americans complained to the government.

In 1925, Kellogg organized a ceremony. It recognized Oneida chiefs and called for federal protection.

Challenges to Kellogg's Work

Kellogg's campaign in New York faced many problems. There was strong resistance from local, state, and federal governments. They pressured Six Nations leaders to stop Kellogg. This led to disagreements within the tribes. There were also efforts to discredit Kellogg. In 1925, Kellogg, her husband, and Chief Wilson K. Cornelius were arrested in Canada.

They also faced many defeats in court. In 1927, a lawsuit to reclaim land was dismissed. Kellogg also lost a suit for control of Onondaga Nation funds. In 1928, Edward A. Everett, Kellogg's main lawyer, passed away.

In 1929, Kellogg sought help from the U.S. Congress. She got a hearing for Haudenosaunee leaders. She spoke proudly of the Six Nations. She talked about her plans for their economic and political revival. She accused the Bureau of Indian Affairs of spreading lies about her. However, her testimony did not convince most senators. An official from the Indian Affairs Bureau accused Kellogg of fraud.

In August 1929, Kellogg faced another setback. A court ruled on a leadership dispute within the Six Nations. This ruling favored an opponent of Kellogg. After this, court appeals were unsuccessful. Many Iroquois supporters were angry that their money did not bring results. Kellogg's long campaign lost momentum.

On July 4, 1937, Kellogg spoke at a Six Nations council. She said, "The Iroquois are struggling for a renaissance." She believed that if they had self-rule, they could show the world a perfect government.

Later Years and Legacy

Kellogg continued her fight for the Six Nations of the Iroquois throughout her life. By the 1940s, historian Lawrence Hauptman said she was "a broken woman." She had lost her fame and money. Kellogg lived her final days on welfare. She passed away in New York City in 1947.

Laura Cornelius Kellogg remains a debated figure in 20th-century Iroquois politics. Many elders saw her as someone who caused divisions. However, her Lolomi Plan was a new idea for Native American self-sufficiency. It predicted later movements to reclaim land and promote self-government.

Kellogg's vision is seen today in the success of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin. Their land holdings have grown greatly since the 1980s. Their economic impact on the Green Bay, Wisconsin area is now over $250 million annually.

|

See also

In Spanish: Minnie Kellogg para niños

In Spanish: Minnie Kellogg para niños