Society of American Indians facts for kids

| Formation | 1911 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1923 |

| Type | Native American rights |

| Purpose | Pan-Indianism |

| Headquarters | United States |

|

Official language

|

English |

The Society of American Indians (1911–1923) was a very important group. It was the first national organization for Native American rights. Native Americans themselves ran it, for Native Americans. This group helped start a big idea called Pan-Indianism. This idea was about all Native American tribes working together. They wanted unity, no matter which tribe someone belonged to.

The Society was a place for new Native American leaders. These leaders were called "Red Progressives." They were professionals like doctors, nurses, lawyers, and teachers. They believed in progress through education and government action. This was similar to what many white reformers thought at the time.

The Society held meetings at universities. They had an office in Washington, D.C. They also held yearly conferences and published a magazine. This magazine featured writings by Native American authors. The Society was one of the first groups to suggest an "American Indian Day." They also fought for Native Americans to become U.S. citizens. They wanted all tribes to be able to take their claims to the U.S. Court of Claims.

A big success for the Society was the Indian Citizenship Law. This law was signed on June 2, 1924. It gave all Native Americans U.S. citizenship. The Society also helped pave the way for the Indian Claims Commission. This commission was set up in 1946. It helped tribes make claims against the U.S. government. Later, these cases moved to the U.S. Court of Claims. The Society of American Indians was a key group. It led to modern organizations like the National Congress of American Indians.

Contents

- What is Pan-Indianism?

- How the Society Started

- First Meeting in Columbus

- Temporary Committee

- First Society Conference

- Red Progressives

- Bureau of Indian Affairs Debate

- McKenzie's Important Role

- Early Achievements

- Impact of World War I

- Peyote Religion and Rights

- The Society's Last Meeting

- Society Leaders Continue to Influence

- Legacy of the Society

- Society's 100th Year Symposium at Ohio State University

- See also

What is Pan-Indianism?

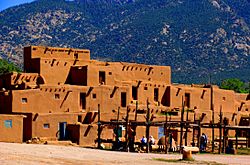

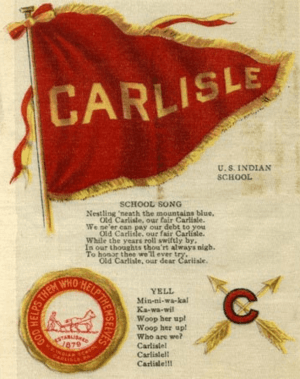

Schools like the Carlisle Indian School and the Hampton Institute were important. These were boarding schools far from reservations. They helped create a new generation of Pan-Indian leaders. The most lasting impact of the Carlisle Indian School was the friendships formed there. Students from many different tribes became lifelong friends. They also built connections between tribes that were far apart.

The school aimed to make students more "American." But mixing students from 85 different Native nations had another effect. It helped create a sense of "nationalizing the Indian." Dr. Carlos Montezuma called Carlisle "a place to think, observe and decide." Students learned about Euro-American customs. But they also learned about other tribes and religions. They saw how the government often treated all tribes unfairly. Carlisle graduates kept in touch across the country. They visited and wrote to each other often.

How the Society Started

In the early 1900s, three important Native Americans had an idea. Dr. Charles Eastman, his brother John Eastman, and Rev. Sherman Coolidge talked about forming a group. They wanted a national organization for Native American rights. But they thought it was not the right time yet. They worried it would not be understood. They also feared it would upset the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

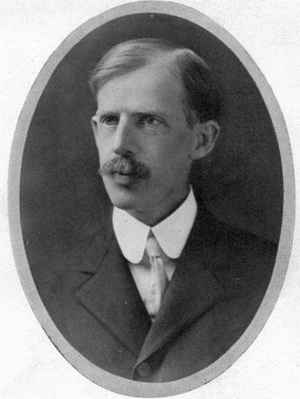

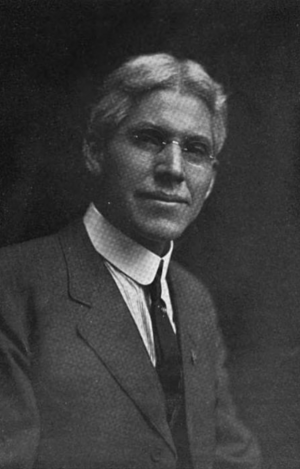

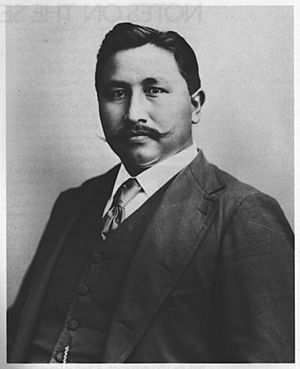

In 1903, Coolidge met with a sociologist named Fayette Avery McKenzie. They talked about forming a national group run by Native Americans. In 1905, McKenzie became a professor at Ohio State University. In 1908, he invited Charles Eastman, Dr. Carlos Montezuma, and Coolidge to speak. They gave talks about "The Indian problem." These talks were very popular. Local newspapers wrote about them. They even printed photos of Coolidge and Montezuma. The three intellectuals gave many speeches. They traveled around the city together.

In 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was formed. McKenzie felt it was time for a similar group for Native Americans. He wrote to Coolidge and Eastman. He suggested a national meeting led by Native Americans. McKenzie believed that Native Americans could do more for themselves. He wanted a group run by and for Native Americans. This was different from "friends of Indians" groups. His first try to organize a meeting in 1909 did not work out.

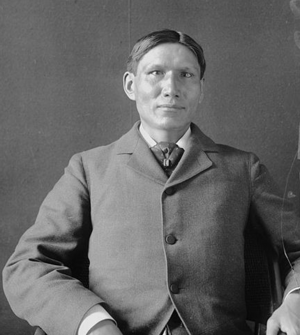

First Meeting in Columbus

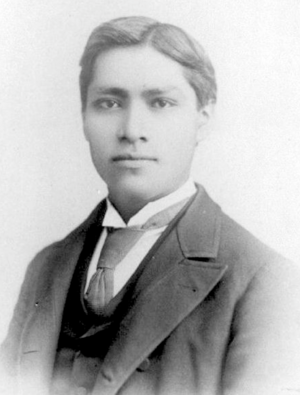

On April 3–4, 1911, McKenzie invited six Native American thinkers to a meeting. It was a planning meeting at Ohio State University. The attendees included Dr. Charles Eastman (Santee Dakota), a doctor. Dr. Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai-Apache), also a doctor, was there. Thomas L. Sloan (Omaha), a lawyer, attended. Charles Edwin Dagenett (Peoria), a government supervisor, was present. Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida), an educator, and Henry Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota), an educator, also came. Arthur C. Parker (Seneca), an anthropologist, was invited. But a fire at his workplace kept him from attending.

After the meeting, the group announced a new organization. It was called the American Indian Association. They planned a big meeting for that fall. They explained why this conference was needed. They wanted to see if past efforts to help Native Americans had worked. They also wanted Native Americans to help themselves. This meant developing a shared identity and leaders. They believed Native Americans had valuable things to offer the government. They hoped to prevent mistakes in policies. They also wanted to show that white people were willing to make up for past wrongs.

On April 5, 1911, newspapers reported on the meetings. They said it was a historic event. It was like the meetings after the Civil War to help freed slaves. They reported that the new group would "better conditions for the Indians." It would also "upbuild a race consciousness." The city of Columbus invited them to hold their next meeting there.

Temporary Committee

Soon after the April meeting, a temporary committee was formed. It had 18 important Native Americans. Charles E. Dagenett (Peoria) was the Chairman. Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida) was the Secretary. Rosa La Flesche (Chippewa) was the Corresponding Secretary and Treasurer. Other members included William Hazlett (Blackfoot) and Harry Kohpay (Osage). Also on the committee were Charles D. Carter (Chickasaw and Cherokee) and Emma Johnson (Pottawatomie). Howard E. Gansworth (Tuscarora) and Henry Roe Cloud (Winnebago) were members. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin (Chippewa) and Robert De Poe (Klamath) were also included. Charles Doxon (Onondaga) and Benjamin Caswell (Chippewa) completed the group. Professor McKenzie was named "Local Representative" in Columbus.

Many committee members were "Indian progressives." They had been educated in white schools. Most of them lived and worked in white society. They thought that Native Americans needed education and hard work to advance. They also believed Native Americans should adopt some white cultural ways.

The committee created a Statement of Purpose. It had six main ideas. These ideas focused on equal rights, good citizenship, and improving the race. They stated that the group would always put "the honor of the race and the good of the country" first. The statement said it was time for Native Americans to work together. They wanted to help their own people and all of humanity.

The principles included promoting Native American progress. They wanted to discuss issues freely at conferences. They aimed to share the true history of their race. They also wanted to preserve records and honor their virtues. Another goal was to promote citizenship and gain its rights. They planned a legal department to solve problems. They also wanted to oppose anything harmful to their race. Finally, they would focus on general principles, not personal interests.

On June 21 and 22, 1911, the committee met again. It was at Laura Cornelius Kellogg's home in Seymour, Wisconsin. Important Oneida lawyers Chester Poe Cornelius and Dennison Wheelock attended. Charles E. Dagenett led the meeting. Emma Johnson, Rosa LaFlesche, and Fayette McKenzie were also there.

On June 25, 1911, the committee sent a message to about 4,000 Native Americans. They stressed the need for an organization. This group would speak for Native Americans. It would also get the attention of the United States.

First Society Conference

McKenzie, as the "Local Representative," organized the first conference. He handled everything from planning to the program. On July 29, 1911, The Washington Post reported on the upcoming event. It said all Native Americans were invited to a conference in Columbus, Ohio. The goal was to plan for the "uplift and betterment of the race." A main purpose was to show Americans that Native Americans were not savages. It would show their great progress in intellect and character. Senators Robert L. Owen and Charles Curtis, and Representative Charles D. Carter supported the meeting. All of them had Native American heritage.

McKenzie planned a special event to get national attention. He worked with Arthur C. Parker to find speakers. They designed the program and got support. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, the city of Columbus, and Ohio State University all endorsed it. Local groups also supported the conference. Ohio State President William Oxley Thompson was impressed. Columbus Mayor George Sidney Marshall also supported it. Many other civic and religious leaders invited the new group. They asked them to hold their first meeting in Columbus. It was set for Columbus Day in October 1911. They hoped to forget past conflicts. They wanted to work for justice, intelligence, and progress. The invitation was accepted.

On October 12, 1911, the Society's first conference began. It was held at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. Holding it on Columbus Day was symbolic. It marked a new beginning for Native Americans. About 50 important Native American scholars, clergy, writers, artists, teachers, and doctors attended. National news media widely reported on the event. University and city officials welcomed the Society. The U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Robert G. Valentine, also spoke. Students from the Carlisle Indian School provided entertainment.

Group discussions covered many topics. These included citizenship, higher education, and Native Americans in professions. They also talked about Native American laws and the future of reservations. On Sunday, participants spoke at various churches. The group organized itself as the American Indian Association. They elected leaders and adopted rules.

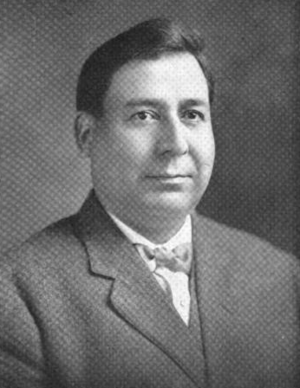

Only Native American delegates attended the business session. Thomas L. Sloan, Rev. Sherman Coolidge, and Dr. Charles Eastman were nominated for Chairman. Sloan won the election. Charles E. Dagenett became secretary-treasurer. Other elected committee members were Hiram Chase, Arthur C. Parker, Laura Cornelius Kellogg, and Henry Standing Bear. The committee was asked to create a constitution. It would be for a larger meeting of all Native Americans. They suggested each tribe send at least two representatives.

Washington, D.C., was chosen as the headquarters. The committee would watch laws affecting Native Americans. They would also work with the Indian Office. Membership was divided into active, Indian associate, and associate classes. Only Native Americans could vote and hold office. Associate members were non-Native Americans interested in Native American welfare. The Society's letterhead clearly stated this. John Milton Oskison (Cherokee) and Angel De Cora (Winnebago) designed the Society's emblem. The group changed its name. It became the "Society of American Indians." This was to show it was a Native American-led movement.

Red Progressives

The first leaders of the Society were called "Red Progressives." They shared the belief of white reformers in progress. They thought education and government action could improve society. These leaders worked hard for their achievements. They believed gains required effort. They saw themselves as self-made people. They were not passive victims of circumstances.

The Society began with hope, not despair. It was seen as a new force in American life. The first conference was held on Columbus Day, October 12, 1911. This was meant to be a new start for Native Americans.

Society members were educated professionals. They worked in medicine, nursing, law, and education. There were no traditional chiefs or tribal leaders among them. The eastern Native American boarding schools, especially Carlisle, were very influential. The strong bond among Carlisle graduates provided many Pan-Indian leaders. Red Progressives stayed connected to tribal life. They used both Native American and American names. Many were children of important tribal leaders. These leaders came from New York, the Great Lakes, Oklahoma, and the Great Plains.

Of the expanded committee, six were from Oklahoma. Almost all were from Eastern, Prairie, or Plains Tribes. Four were from the Six Nations Confederacy tribes. Two were Lakota, and two were from the Five Civilized Tribes. Three were Chippewa. There was one each from the Blackfoot, Pottawatomie, Winnebago, Omaha, Osage, Apache, and Klamath tribes. Many came from progressive families. They also had social and marriage ties to non-Native Americans. Many also worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They used their education to fight for Native American rights.

In April 1912, the Society's membership grew. It reached 101 active members. About one-third of them were women. There were also about 100 non-Native associate members. By 1913, active members increased to nearly 230. They represented almost 30 tribes. Members included Arthur Bonnicastle (Osage), a community leader. Gertrude Bonnin (Yankton Dakota), an educator and author, was also a member. Rev. Benjamin Brave (Oglala Lakota), a minister, joined. Estaiene M. DePeltquestangue (Kickapoo), a nurse, was part of the group. William A. Durant (Choctaw), a lawyer, and Rev. Philip Joseph Deloria (Onondaga), a priest, were members. Rev. John Eastman (Santee Dakota), a minister, and Father Philip B. Gordon (Chippewa), a priest, also joined. Albert Hensley (Winnebago), a missionary, and John Napoleon Brinton Hewitt (Tuscarora), a linguist, were members. William J. Kershaw (Menominee), an attorney, and Susan LaFlesche (Omaha), a doctor, were also involved. Francis LaFlesche (Omaha), an anthropologist, and Rev. Delos Lone Wolf (Kiowa), a minister, were members. Louis McDonald (Ponca), a businessman, and Luther Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota), an educator, joined. Dennison Wheelock (Oneida), a musician and lawyer, and Chauncey Yellow Robe (Sicangu Lakota), an educator, were also members.

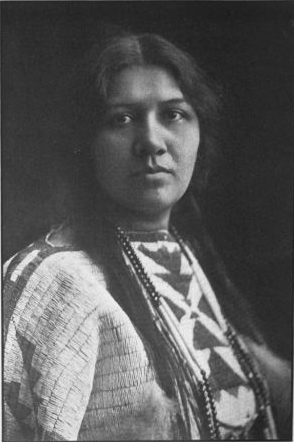

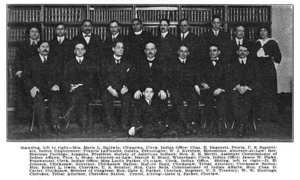

The official photo of the first conference shows members in modern clothes. Native American clergy wore clerical collars. There was little "Indianness" in their outfits. Only Nora McFarland from Carlisle wore a traditional dress. The Society opposed Wild West shows and circuses. They believed these shows were harmful to Native Americans. They discouraged Native Americans from joining them. Chauncey Yellow Robe wrote that Native Americans should be protected. He said Wild West shows led them to "the white man's poison cup." Red Progressives thought these shows used Native Americans unfairly. They strongly opposed stereotypes of Native Americans as savages. From 1886 to World War I, reformers fought against these images. They promoted the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. It showed a new generation of Native Americans. These new Native Americans embraced education and industry.

Many things influenced the Society's early path. Pan-Indianism grew as modern social science developed. Sociologists and anthropologists helped define a common "race." Reformers of the Progressive era loved creating organizations. They turned ideas into actions. They believed problems could be solved. Arthur C. Parker, an anthropologist, imagined an "Old Council Fire." It would include Native American men and women from all tribes. He thought the Society should be like "friends of Indians" groups. It should meet at universities, not reservations. It should have a Washington office and publish a magazine. It would hold yearly conferences. It would also be a way to express a shared Pan-Indian identity.

Christianity and Freemasonry were very important to the Society. Christian ideas of brotherhood and equality matched anthropological ideas. Most Red Progressives were Christians. Some were ministers or priests. Others were religious peyotists from Christianized tribes. Freemasonry also influenced Pan-Indianism in the 1920s. Almost every Native American man in the Society was a Freemason. Arthur C. Parker, who used his Seneca name "Ga-wa-so-wa-neh," wrote about American Indian Masonry. He said Masonry was linked to Native Americans. He noted that the Iroquois, especially the Senecas, were "inherent" Freemasons. He believed Masonry offered a way to succeed in the white world. It would also preserve the memory of Native Americans.

Bureau of Indian Affairs Debate

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was a big topic of debate in the Society. Many Native Americans disliked the BIA. They saw it as a symbol of white control. They thought Native Americans working for the BIA were against their own people. McKenzie noted that many Native Americans feared the government. They felt that government employees could not speak freely. At the first conference, Charles Edwin Dagenett was elected Secretary-Treasurer. He was the highest-ranking Native American in the BIA. This made some Native Americans suspicious of white control.

Society leaders argued if the BIA and reservation system should be ended. They also debated if BIA employees could be loyal to their "race" and the Society. Dr. Carlos Montezuma and Father Philip B. Gordon thought it was impossible. They believed BIA employees could not be loyal to both. But Rev. Coolidge, Marie Baldwin, and Gertrude Bonnin disagreed. They thought BIA employees could be loyal to both. Montezuma hated the BIA and reservation life. He soon believed the Society was controlled by the BIA. At the 1915 conference, Coolidge was re-elected president. Arthur C. Parker became secretary. William A. Durant replaced Dagenett as first vice-president. After this, Dagenett and Rosa B. Laflesche left the Society.

The BIA employed many Native Americans. The debate about "race loyalty" cut off a major group of the Society's members. Sloan, who wanted to be the U.S. Indian Commissioner, urged caution. He said the BIA was necessary for many government employees. If reservations were ended, many people would lose their jobs. Most leaders wanted to abolish the BIA and end the reservation system. But they also worried about older Native Americans. They didn't want them to be taken advantage of. They also wanted to protect Native American land.

McKenzie's Important Role

Fayette Avery McKenzie was the first American sociologist to study Native American affairs. He criticized the government's policies. He also had good connections in Washington, D.C. Arthur C. Parker, the Society's Secretary, called McKenzie the "father of the movement." McKenzie respected the Society's goal of being "for Indians and by Indians." He understood Native Americans' distrust of white people. McKenzie downplayed his role. He worked behind the scenes. He wrote to Parker that his race might make people doubt him. He also worried people might think he had hidden motives.

Parker wanted the Society to be run by Native Americans. But he still wanted McKenzie's advice. Parker soon felt overwhelmed by the work. He thought about quitting. McKenzie urged him to stay. He said Parker might be the only one who could save the situation. He told Parker to keep everyone connected and happy. Parker and McKenzie worked together to manage the Society. Their tasks included publications, planning meetings, and lobbying for laws.

McKenzie's main goals were harmony and unity within the Society. He wanted them to work with the white establishment. He also wanted to uphold high standards for Native Americans. He believed that unity was more important than any specific issue. McKenzie had many connections in Washington, D.C. By 1914, he got over 400 non-Native associate members. These were influential academics and politicians. Parker was very thankful for McKenzie's help. In 1913, Parker suggested McKenzie for Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He praised McKenzie's experience and knowledge. McKenzie and Parker worked together until 1915. Then McKenzie left Ohio State to become President of Fisk University. They remained friends and colleagues for life.

Early Achievements

In 1913, the Society was doing very well. Active membership grew to over 230 people. They represented almost 30 tribes. Associate membership grew to over 400. These included people from the American Indian Defense Association. Missionaries, business people, and academics also joined. Many white BIA employees and educators from Native American schools joined too. The future of the organization looked bright. The Society was similar to white reform groups. It was also like the growing Black movements of that time. Its members were middle-class and well-educated. They promoted self-help, race pride, and responsibility.

Denver Platform

The conference in Denver, Colorado, in October 1913, was very important. It was probably the most representative and friendly meeting. Rev. Sherman Coolidge and Arthur C. Parker were reelected. William J. Kershaw became first-vice president. Charles E. Dagenett was elected second vice president. Parker often called the "Denver Platform" the ideal statement of the group's goals. In 1914, the Society opened an office in Washington, D.C. It was across from the Indian Office. They worked to pass two important laws. These were the "Carter Bill" and the "Stephens Bill."

The Carter Bill was introduced by Oklahoma Congressman Charles D. Carter. He was Chickasaw and Cherokee. This bill would make every Native American born in the U.S. a citizen. It would give them all the rights of citizens. The Stephens Bill wanted to open the United States Court of Claims to Native American tribes. This would help settle old land claims. Before, tribes needed a special act of Congress to bring claims to court. McKenzie and Parker believed these laws would bring peace of mind to Native Americans. They would ensure justice without high costs or exploitation.

In February 1914, the Executive Committee met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This meeting was more formal than usual. It included a banquet. In October 1914, Dennison Wheelock hosted the annual meeting in Madison, Wisconsin. In December 1914, the Society met in Washington, D.C. The federal government gave them a warm welcome. Commissioner Cato Sells welcomed them. They toured the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They also visited the White House to meet President Woodrow Wilson. Wheelock shook hands with the president. He then presented the Society's request. They asked for support for the Carter Bill and Stephens Bill. Wheelock said it was strange to have groups of people in the nation with different civic conditions. President Wilson was impressed. But both bills did not get much support in Washington. Arthur C. Parker noted that there was prejudice against Native American issues.

American Indian Day

The Society of American Indians was one of the first groups to propose an "American Indian Day." This day would honor the important contributions of the first Americans. In 1915, Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca, convinced the Boy Scouts of America to set aside a day. They called it "First Americans" day for three years. In September 1915, the Society formally approved the idea. This was at their conference in Lawrence, Kansas. Society President Rev. Sherman Coolidge asked for recognition of Native Americans as citizens. He called for a national "American Indian Day." In response, the President issued a statement on September 28, 1915. It declared the second Saturday of each May as American Indian Day.

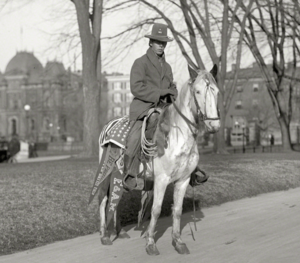

In 1916, Governor Charles S. Whitman of New York declared the first official state American Indian Day. It was on the second Saturday in May. The year before, Red Fox James (Blackfoot), a Society member, rode horseback across states. He sought approval for a day to honor Native Americans. On December 14, 1915, he presented support from 24 states at the White House. However, there is no record of a national day being officially proclaimed. Today, several states celebrate the fourth Friday in September. In Illinois, for example, a law for such a day was passed in 1919. Currently, some states call Columbus Day "Native American Day." But it is not a national legal holiday. In 1990, President George H. W. Bush approved a resolution. It named November 1990 "National American Indian Heritage Month." Similar statements have been issued every year since 1994.

Impact of World War I

As the U.S. got closer to World War I, the Native American reform movement slowed. The Society also faced internal problems. In 1917, a debate started. The government proposed a separate Native American U.S. Army regiment. Supporters included Francis LaFlesche and Gertrude Simmons Bonnin. Carlos Montezuma, Father Gordon, and Red Fox St. James also supported it. However, Parker and the magazine editors opposed it. They believed Native Americans should not be separated from other Americans. They felt the idea came from Wild West shows.

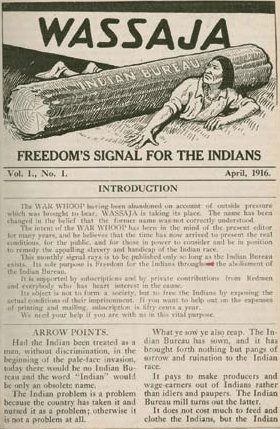

Debates continued about ending reservations and the BIA. They also discussed banning the use of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies. From 1916 to 1922, Carlos Montezuma published his own newsletter, Wassaja. It shared his "radical" reform views. Arthur Parker was often attacked in Wassaja. He tried to separate the magazine from the Society. He wanted to build a new organization. Parker then published the first issue of the American Indian Magazine in 1916. He replaced Montezuma and Dennis Wheelock as editors. He brought in Grace Wetherbee Coolidge, Rev. Sherman Coolidge's wife, and Mrs. S.A.R. Brown. Both were white. For the first time, Native Americans did not control the Society's publication.

Parker attacked "the peyote poison." He criticized its defenders like Thomas L. Sloan. Sloan represented peyote users in court. Parker also called for Congress to dissolve tribes as legal groups. He emphasized the patriotism of Native Americans serving in the war. The last issue of the American Indian Magazine for 1917 was special. It focused on the Sioux people. This was due to Gertrude Simmons Bonnin's efforts. She also tried to get Charles Eastman interested in the Society again. As Parker spent less time on the Society, Bonnin spent more. The American Indian Magazine was published for three more years. The last issue was in August 1920. The American Indian Tepee, started in 1920, became an unofficial paper for the Society. It supported Society President Thomas L. Sloan for U.S. Indian Commissioner. It also reported Society news.

Peyote Religion and Rights

The use of peyote in religious ceremonies was a big and often debated topic within the Society. In the 1870s, a new religion formed on reservations in what is now Oklahoma. This religion used peyote in its rituals. It combined older ceremonies from Mexico with traditions from Southern Plains tribes. By the early 1880s, the peyote religion became more unified. It spread to other tribes in the area. By 1907, when Oklahoma became a state, the religion had spread widely. This was helped by tribes visiting and marrying each other.

In 1918, important Society leaders spoke to the U.S. Congress. They argued for and against the "Hayden Bill." This bill, proposed by Congressman Carl Hayden, aimed to stop the use of alcohol and peyote among Native Americans. Gertrude Simmons Bonnin and Charles Eastman spoke against peyote. Supporters of the peyote religion included Thomas L. Sloan and Francis LaFlesche. Cleaver Warden and Paul Boynton also supported it.

After these hearings, former Carlisle Indian School students and other leaders formed a group. They founded the Native American Church of Oklahoma in October 1918. Society lawyers Sloan and Hiram Chase argued that peyote was an "Indian religion." They said it was like an "Indian version of Christianity." They believed it deserved the right to religious freedom. The Native American Church mixed Native American and Christian beliefs. It was popular among educated men in tribes like the Winnebago and Omaha. Henry Roe Cloud, a Winnebago, admitted the religion attracted smart men in his tribe. But he personally opposed its use. Oliver Lemere, a former Carlisle student, was drawn to the religion. He liked its mix of Christianity and Winnebago customs. He also noted that its followers were progressive members of the tribe.

By 1934, the Native American Church of Oklahoma was a very important Pan-Indian religious movement. Its leaders started churches in other states. The church's founding documents from 1918 and 1934 had the same people. This showed that Carlisle alumni continued to lead Pan-Indianism. In 1945, the Native American Church in Oklahoma was renamed. It became "The Native American Church of United States."

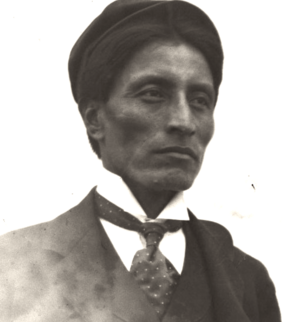

The Society's Last Meeting

In 1923, the Society held its last meeting in Chicago. By this time, the group was almost inactive. Disagreements about the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Peyote religion had caused many leaders to leave. Carlos Montezuma had invited them to Chicago. But by the time of the meeting, he was very ill. He decided to return to his reservation to die. He and his wife left Chicago for the Fort McDowell Yavapai Reservation in Arizona. He died there on January 31, 1923, in a simple hut. After years of saying he would not "go back," he did. Montezuma was dedicated to Pan-Indianism. But he chose to die as a Yavapai.

Thomas L. Sloan and other Society members visited the Chicago Bar Association. They tried to get interest in Native American affairs. But the meeting in Chicago was overshadowed by a Native American encampment. This camp was held near the city. Thousands of Chicagoans came to see the "informal gala." They watched Native American dances and ceremonies. The public was more interested in the "exotic" Native American past. They were less interested in the reality of Native American life today. William Madison, a Minnesota Chippewa and the Society's treasurer, expressed his sadness. He said the public only cared when Native Americans performed war dances or old ceremonies. After years of low attendance, the Society ended quietly. It disbanded after its thirteenth convention in Chicago.

The Society did not have enough agreement within itself to achieve all its goals. However, former Society leaders went on to play important roles. They influenced groups like the American Indian Defense Association. They also helped with the Committee of One Hundred and the Meriam Report.

Society Leaders Continue to Influence

Even after the Society disbanded in 1923, its leaders continued to shape Native American affairs. In May 1923, Society leaders joined with reformer John Collier. They founded the American Indian Defense Association. This group was formed because of unfairness to the Pueblos of New Mexico. These injustices came from the Bursum Bill (1921) and the Dance Order (1923).

In 1921, Senator Holm O. Bursum proposed a bill. This bill would have taken large parts of Pueblo lands. It would give them to people who had settled there without permission. By 1922, Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall strongly supported this "Bursum Bill." By 1923, the struggles of the Pueblos became widely known. They became a symbol of unfairness to Native Americans. The Pueblos had governed themselves for hundreds of years. Each Pueblo owned its lands together as a community. These lands were given to them by the King of Spain. The U.S. Congress later confirmed these grants.

Also in 1923, Commissioner Charles H. Burke issued a "Dance Order." This order told superintendents to discourage "giveaways." These were part of many tribes' ceremonies. It also banned any dances the agent thought were immoral or dangerous. The Dance Order was issued because of lobbying by the Indian Rights Association and missionaries. They opposed the growing influence of the Peyote religion. The order threatened the Pueblo Indians' right to perform their traditional dances. The American Indian Defense Association became a powerful group in Washington. They successfully fought against the government taking communal Native American lands. They also fought against limiting religious freedom. The Bursum Bill was defeated, and the Dance Order was withdrawn.

In 1923, the American Indian Defense Association gained momentum. Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work invited a group of Americans to form an "Advisory Council on Indian Affairs." This group became known as the "Committee of One Hundred." They would review and advise on Native American policy. The group included many distinguished people. Among them were Bernard M. Baruch and William Jennings Bryan. Also included were Gen. John J. Pershing and William Allen White. John Collier and M.K. Sniffen were also members.

On December 12 and 13, 1923, the Committee of One-Hundred met in Washington, D.C. Many former Society leaders were there. These included Rev. Sherman Coolidge, Arthur C. Parker, and Dennison Wheelock. Charles Eastman, Thomas L. Sloan, and Father Philip Gordon also attended. Henry Roe Cloud, J.N.B. Hewitt, and Fayette Avery McKenzie were present. Parker and McKenzie worked together again. Parker led the Committee sessions. McKenzie chaired the resolutions subcommittee. McKenzie noted that the Committee's goals were similar to the Society's earlier ideas.

In 1926, the committee's suggestions led to a study. The Coolidge administration asked Lewis M. Meriam and the Brookings Institution to study Native American conditions. Henry Roe Cloud and Fayette McKenzie were important contributors to this study. In February 1928, their findings were published. This report was called "The Problem of Indian Administration." It is known as the Meriam Report. The Meriam Report showed how federal policies had failed. It documented serious problems with Native American education, health, and poverty. The Meriam Report marked a big change in Native American policy. It laid the groundwork for the Indian New Deal. This happened under John Collier during President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's time.

Legacy of the Society

The Society of American Indians was the first national Native American rights group. It was run by and for Native Americans. It helped start Pan-Indianism in the 20th century. The Society was a place for a new generation of Native American leaders. The Society's Denver Platform of 1914 called for Native American citizenship. It also pushed for the U.S. Court of Claims to be open to all tribes. Former Society leaders continued to influence Native American affairs. They worked with the American Indian Defense Association. They also served on the Committee of One Hundred. They helped write the Meriam Report of 1928. The Society was a pioneer for modern Native American organizations.

In 1944, the founding conference of the National Congress of American Indians was held. It was very similar to the Society's first conference in 1911. Members of the Congress were educated professionals. They were doctors, nurses, lawyers, and teachers. Many had attended Carlisle Indian School or Haskell Institute. They were college graduates. The first president was Judge Napoleon B. Johnson. He was a college graduate and a Freemason. The first secretary, Dan M. Madrano, also went to Carlisle. He studied at the Wharton School of Business and the National Law School. He was also a Freemason. The council included anthropologist D'Arcy McNickle. Arthur C. Parker and Henry Standing Bear made brief appearances as respected elders.

Like the Society, the Congress debated if BIA employees could hold office. They decided they could. The Congress dealt with familiar issues. These included legal aid, laws, education, and starting a publication. The Congress focused on big problems affecting all Native Americans. Like the Society, it wanted to avoid small disputes. This would keep its broad representative character. At first, only people "of Indian ancestry" could be members. Membership was for individuals and groups. Later, non-voting non-Native associates were allowed. Today, the Congress is still the most important Pan-Indian reform group. Non-Native members still come from similar groups as in the Society's time. These include church groups, progressives, and social scientists.

Society's 100th Year Symposium at Ohio State University

In 2011, the American Indian Studies Program (AIS) at Ohio State University celebrated. It marked 100 years since the Society of American Indians was founded. Scholars from across the country attended. The event was held on Columbus Day weekend. Keynote speeches were given by important Native American scholars. These included Philip J. Deloria, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, and Robert Warrior. Following the tradition of the Society's first meeting, the symposium included a trip. They visited the Newark Earthworks in Newark and Heath, Ohio. These earthworks are 2,000 years old. They were built by Native American people. They served as places for ceremonies, star gazing, gatherings, trade, and worship.

See also

In Spanish: Sociedad de Indios Americanos para niños

In Spanish: Sociedad de Indios Americanos para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |