Cupeño facts for kids

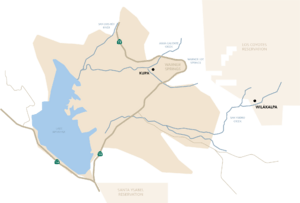

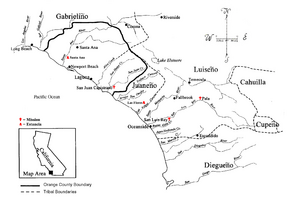

The lands of different Native American tribes in Southern California, including the Cupeño language

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,000 (1990) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, formerly Cupeño language | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Cahuilla, Luiseño, Serrano, and Tongva |

The Cupeño are a group of Native American people from Southern California. In their own language, their name is Kuupangaxwichem, which means "people who slept here."

They traditionally lived about 50 miles (80 km) inland. This was north of where the U.S.-Mexico border is today. Their homes were in the Peninsular Range mountains of Southern California. Today, their descendants are part of federally recognized tribes. These include the Pala Band of Luiseno Mission Indians, Morongo Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians, and Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla and Cupeno Indians.

Contents

Cupeño History and Lands

The Cupeño culture came together between 1000 and 1200 AD. They were very similar to the Cahuilla people. The Cupeño traditionally lived in the San Jose Valley mountains. This area is near the start of the San Luis Rey River.

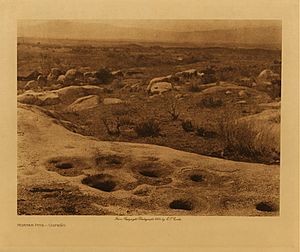

They lived in two main villages, Wilákalpa and Kúpa (also called Cupa). These villages were north of what is now Warner Springs, California. They also lived at Agua Caliente, east of Lake Henshaw. This area is crossed by State Highway 79 near Warner Springs. The old village site of Cupa is about 200 acres (0.81 km2). It is now empty, but it is still important for its history.

Arrival of Europeans

Spaniards first came to Cupeño lands in 1795. By the 1800s, they had taken control of these lands. After Mexico became independent, its government gave a large piece of land to Juan Jose Warner. This was about 45,000 acres (182 km2) on November 28, 1844.

Warner, like many other landowners, used Native American workers. The people from Kúpa village did most of the work on Warner's cattle ranch. The Cupeño continued to live at Agua Caliente after the Americans took over California in 1847-1848. This was during the Mexican–American War. They built a ranch house in 1849 and a barn in 1857, which are still there.

Life at Warner's Ranch

Julio Ortega, an elder of the Cupeño tribe, said that Warner set aside about 16 miles (26 km) of land around the hot springs for the Native Americans. Warner encouraged the Cupeño to build a stone fence around their village. This would keep their animals separate from the ranch's animals. Ortega believed that if the village had made its own clear boundaries, the Cupeño would still live there today.

In 1846, an American Army officer named W. H. Emory visited the Cupeño. He wrote that Warner treated the Native Americans like serfs, which means they were forced to work for him. He also said they were treated badly. In 1849, Warner was arrested by American forces. He was accused of working with the Mexican government and was taken to Los Angeles.

The Garra Revolt

In 1851, a Yuma Indian named Antonio Garra tried to unite different Southern California tribes. He wanted to force all the European Americans out. His plan, called the Garra Revolt, failed. Settlers then executed Garra. The Cupeño had attacked Warner and his ranch, burning some buildings. Their own settlement at Kúpa also lost structures. Warner sent his family away but kept running the ranch through others.

Before they were forced to leave, the Cupeño sold milk, animal feed, and crafts to travelers. These travelers used the Southern Immigrant Trail and the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoaches. These stagecoaches stopped at Warner's Ranch. Cupeño women made lace and washed clothes in the hot springs. The men carved wood and made saddle pads for horses. They also raised cattle and farmed about 200 acres (0.81 km2) of land. In 1880, John G. Downey, a European-American, bought the main part of Warner's Ranch.

Forced Relocation

In 1892, John G. Downey, who used to be the governor of California, started legal action. He wanted to remove the Cupeño from the ranch property. The legal fight continued until 1903. The court ruled against the Cupeño in a case called Barker v. Harvey. The United States Government offered to buy new land for the Cupeño, but they said no.

In 1903, Cecilio Blacktooth, the Cupeño chief at Agua Caliente, famously said: "If you give us the best place in the world, it is not as good as this. This is our home. We cannot live anywhere else; we were born here, and our fathers are buried here."

On May 13, 1903, the Cupeño people were forced to move. They went to Pala, California, on the San Luis Rey River, about 75 miles (121 km) away. Today, many Cupeño descendants live on reservations like Los Coyotes, San Ygnacio, Santa Ysabel, and Mesa Grande. Many Cupeño still believe their land at Kúpa will be returned to them. They are working to make this happen. The Cupa site is a symbol for Native American groups who want to get back their cultural and religious lands.

Cupeño Culture and Traditions

The Cupeño tribe is split into two main groups, called moieties: the Coyote and the Wildcat. These groups are further divided into several clans. Clans are like large family groups. Hereditary male leaders and assistant leaders lead the clans. Traditionally, marriages were arranged by families.

Traditional foods included acorns, cactus fruit, seeds, and berries. They also hunted deer, quail, rabbits, and other small animals.

The Cupa Cultural Center was started in 1974 in Pala. It was made much bigger in 2005. The center shows artwork and offers classes. You can learn basket making, beading, and the Cupeño language there. Every first weekend of May, the center celebrates Cupa Days.

Cupeño Language

The Cupeño language is part of the Cupan group. This group also includes the Cahuilla and Luiseño languages. These languages belong to the Takic branch of the large Uto-Aztecan language family. Roscinda Nolasquez (1892–1987) is thought to be the last person who spoke Cupeño fluently.

Today, the language is mostly considered extinct. In 1994, a language expert named Leanne Hinton thought only one to five people still spoke Cupeño. The 1990 U.S. census reported nine people spoke it. Even though it's rare, there are learning materials for the language. Young people still learn to sing in Cupeño, especially traditional Bird Songs.

Cupeño Population

Alfred L. Kroeber estimated that about 500 Cupeño people lived in 1770. Lowell John Bean and Charles R. Smith thought there were between 500 and 750 in 1795. By 1910, the Cupeño population had dropped to 150, according to Kroeber. Later estimates suggest there were fewer than 150 Cupeño in 1973, but about 200 in 2000.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |