Yuma War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Yuma War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

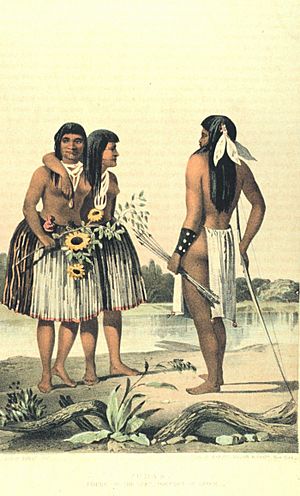

Yumans along the Colorado River by William Emory, circa 1857. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Cupeno (1852–1853) Cocopah (1853) Paipai Halyikwamai Mountain Cahuilla(1851) |

Yuma Mohave Cocopah (1850–1853) Cahuilla Cupeno (1851) Mountain Kumeyaay (1851) |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Juan Antonio (Cahuilla) |

Huttami Cavallo y Pelo Santiago Vicente Macedon Jose Maria Irataba Antonio Garra † Chipule † Cecili † |

||||||

The Yuma War was a series of military actions by the United States in southern California and what is now southwestern Arizona. It took place from 1850 to 1853. The main group fighting the United States Army was the Quechan people. However, the Americans also fought other Native American groups in the area.

Why the Yuma War Started

After the Mexican Cession, many American settlers moved west. They were heading to California for the California Gold Rush. Many of them crossed the Colorado River through lands belonging to the Quechan people.

The Quechan saw a chance to start a business. They set up a ferry service near where the Gila and Colorado Rivers met. This ferry helped American settlers cross the river on their way to California. This made white American ferry businesses angry, as they also operated on the Colorado River.

The Glanton Gang Incident

In early 1850, a California outlaw named John Joel Glanton and his group of twelve men teamed up with another ferry business. They tried to hurt the Quechan ferry operations and destroyed their ferry. The Glanton gang also stole from and harmed Americans, Mexicans, and Native Americans traveling near the river. They even bothered the local Quechan chief.

In response, a group of Quechan warriors attacked Glanton's gang. They killed nine of them. News of this attack spread to California. This event led to the start of the Yuma War.

California's First Response

California reacted by sending the Gila Expedition. This was a group of 142 militia members. They were paid $6 a day to fight the Quechan, which was a lot compared to gold panning. The expedition started on April 16. It entered what is now Arizona.

However, the expedition was surrounded and defeated in September after several small fights. The Gila Expedition failed. Because of the high prices during the gold rush, it cost California $113,000. This amount almost made the state go broke.

The U.S. Army Steps In

After California's militia failed, the United States Army sent the Yuma Expedition. Captain Samuel P. Heintzelman led this group. Their goal was to set up a military post at Yuma Crossing on the Colorado River. This spot was near where it met the Gila River. The post would protect travelers going to California. It would also stop any fighting from the Quechan people.

Heintzelman left San Diego on October 3, 1850. He had three companies of soldiers. Another company set up a supply base at Vallecitos. Heintzelman sent a small group ahead to dig wells in the desert. He reached Vallecitos on November 3 and Yuma Crossing on November 27. A third company arrived a few days later.

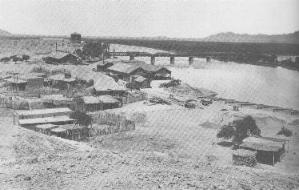

They set up Camp Yuma. Tents were protected from the sun and wind by brush and reed fences. They also started a garden and vineyard near the river. The Quechan people living nearby were calm and friendly.

In February 1851, Heintzelman met with some Quechan leaders. He gave them tobacco, food, and other gifts. The Quechan were happy. They told him they were afraid of the Maricopa people. The Maricopa lived along the Gila River and were raiding Quechan villages. Heintzelman tried to arrange peace between the Quechan and Maricopa.

Supply Problems and Evacuation

Getting supplies became a problem. Supply wagons were late and did not bring enough food for the troops. Supplies sent by sea from San Diego also did not arrive as planned. When they did, boats struggled to bring them up the river. Bringing supplies overland by wagon was difficult but more successful.

Heintzelman asked for a steamboat to bring supplies up the river. But supplies became dangerously low. Also, the local Quechan's crops had failed. They were asking the camp for food. In June 1851, Heintzelman was ordered to leave the camp. Only a small group of ten men stayed behind to guard the ferry. Lieutenant Sweeny led this small group.

Fort Yuma Under Attack

During the camp's early days, there was no fighting between the Quechan and the American army. This was because of the peace Heintzelman had made. But this peace did not last.

In October 1851, Lieutenant Sweeny sent a letter to San Diego. He asked Heintzelman for immediate help at the fort. Supplies were low, and many soldiers were sick. Dozens of Quechan warriors had surrounded the post. Sweeny expected an attack. Heintzelman replied that he did not believe the Quechan were hostile.

But then news arrived that four of Sweeny's men had been killed. About 800 Quechan, Cocopah, and Mohave warriors were involved. Heintzelman then sent sixteen men under Captain Delozier Davidson with mules and wagons. The group arrived at the fort on December 6. But they soon left it for a new camp six miles south, near Pilot Knob.

Garra's Revolt and Tax Issues

In 1851, San Diego County started charging property taxes to Native American tribes. They threatened to take land if the tribes did not pay the $600 tax. This new tax affected the Cupeño and Kumeyaay tribes. They rarely used U.S. money.

These two tribes agreed to join the revolt with the Cocopah and Quechan in the Yuma War. However, the Kumeyaay did not promise to attack San Diego.

The Garra Revolt began with an attack on Warner's Ranch. This uprising was led by Antonio Garra of the Cupeño tribe. The Cahuilla and nearby Kumeyaay joined the attack. Warner's Ranch was known for treating Native Americans poorly.

Heintzelman learned about the December 1851 raid by the Cahuilla and Cupeño. It happened at Warner's Ranch and Agua Caliente in the San Felipe Mountains. Antonio Garra led this revolt. Americans in California were very worried about fighting so close to their settlements. In San Diego, people started getting ready to defend the town.

In response, Heintzelman began the Agua Caliente Expedition. This was a march to the San Felipe Mountains.

Battle of Coyote Canyon

Just northeast of Agua Caliente, Heintzelman's soldiers met 100 Cahuilla warriors. Chief Chipule led them. The battle happened at Battle of Coyote Canyon on December 21, 1851. Six warriors were killed, including Chief Chipule and Chief Cecili. The Native Americans mostly had bows and were forced to retreat.

From Coyote Canyon, Heintzelman continued northeast into the mountains. They found a village with items from Warner's Ranch. The village was empty, but Heintzelman had it burned. Then he returned to Agua Caliente.

After losing their villages, the Cahuilla decided to surrender. Jonathan Warner helped as an interpreter in a court case. Four Cahuilla chiefs were found guilty of raiding Warner's Ranch. They were accused of killing people, burning the place, and stealing. These four chiefs were executed by firing squad on December 25, 1851.

Garra was captured by the Mountain Cahuilla leader Juan Antonio. He was handed over to a volunteer group from Los Angeles. Garra was later tried and executed in San Diego on January 10, 1852.

After this, relations between the Cahuilla and Cupeño worsened in 1852. The two tribes began to fight each other.

Campaigns Along the Rivers

Colorado River Fights

Heintzelman stayed in San Diego for a few months. He planned a second expedition to secure Fort Yuma. The expedition sailed up the Colorado River in February 1852. But one boat got swamped, so they had to land and reach Fort Yuma by land.

Edward H. Fitzgerald left Fort Yuma to meet Heintzelman's men. Eighteen miles from Yuma, Fitzgerald's men were attacked by the Quechan. The fight lasted 18 hours. One American and four Quechan died. Fitzgerald had to retreat to the fort. They fought again at the Battle of San Luis. The Quechan again defeated the Americans, who lost sixty men.

In late March 1853, soldiers from Fort Yuma organized a second expedition. Captain Fitzgerald and Captain Davidson led eighty infantry and cavalry. It was not very successful. The Quechan were warned and left their villages without a fight. Only twenty Quechan were seen, and one old man was captured.

Lieutenant Frederick Steele launched another operation. With forty men, Steele went up the western bank of the Colorado River. He had one skirmish. A small group of Quechan were found and attacked as they fled across the river. Several Quechan were reportedly killed. Lieutenant Steele continued and destroyed some Quechan fields before returning to the fort.

American civilians told the captain that a large group of Quechan were forty miles north. Thirty men were sent to investigate. But they returned to Fort Yuma after traveling seventy miles without finding the enemy. In mid-May, the soldiers did several scouting missions around the fort.

In one mission, Lieutenant Sweeny and twenty-five men attacked a village south of Fort Yuma. They killed one warrior, accidentally wounded a woman, and burned the village. Much clothing and food were also destroyed. Lieutenant Henry B. Hendershott led another group into Quechan land. Two villages were destroyed, along with several wheat fields. Two warriors were killed. In a fourth operation, First Lieutenant George Pearce and his men killed three warriors and wounded Chief Pasqual. One woman was also wounded, and a child drowned in the Colorado.

Battle of the Gila River

In August, Ambrosio Armijo of New Mexico was bringing 9,000 sheep near the fort. He sent a message to Heintzelman. He said that Native Americans had been bothering his group since he passed the Pima Villages. Many of his sheep had been taken by the Pimas and Maricopas. The Quechan were now threatening his group.

Heintzelman immediately sent fourteen men under Lieutenant Sweeny for protection. As soon as Sweeny crossed the Colorado, he sent a message back. He expected to be attacked by about 800 warriors. One of Armijo's sheep herders had been killed. Heintzelman quickly moved all his soldiers across the river, expecting a major battle. Reports said Apaches, Mohaves, and Maricopas were part of the 800-man force.

It was almost dark when the soldiers left the fort. Heintzelman marched along the southern bank of the Gila all night and into the next morning. He did not realize he had passed Armijo's camp. When the captain realized he was going the wrong way, he sent a group back down the Gila. Before they went a mile, they met 100 to 150 mounted Quechan and Cocopah warriors.

The group returned to Heintzelman's soldiers, who were only infantry. The captain tried to outsmart the Native Americans. He split his force into two and sent one to attack the side of the warriors. However, as soon as the flanking group moved, the Quechan and Cocopahs fired rifles and arrows. Flanking failed, so Heintzelman ordered a charge with all his men. But before the Americans could get close, the Native Americans scattered into the hills. Two Americans were wounded, along with at least two Native Americans.

Peace Treaty

In October 1852, the Quechan surrendered to Heintzelman. A peace treaty was made between the Quechan tribes and the U.S. Many of the war chiefs in the region were part of this treaty.

Second Yuma War

| Second Yuma War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cocopah Paipai Halyikwamai |

Yuma Mohave |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Macedon † Irataba Kapetame Asikahota Tapaikuneche Hatsurama |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 dead | 41 dead | ||||||

After the peace treaty, the Cocopah ended their alliance with the Quechan. Conflict broke out in May 1853. First, the Cocopahs attacked three Quechan villages. They killed Chief Macedon, four other warriors, and ten women and children. Twelve prisoners were taken, and a herd of Quechan horses was captured.

The Cocopahs then attacked Chief Jose Maria's camp. They killed three men and twenty-three women and children. Heintzelman noted that this was an "unprovoked aggression" by the Cocopah. A group was sent to the attack site, which was in Mexican territory (now Arizona). The bodies were burned according to Native American tradition. Then the group returned to the fort.

Days later, Chief Maria arrived at Fort Yuma. He told Heintzelman that the high Cocopah chief had released some Quechan women and children. But most were still captive. Maria also said the Cocopah were retreating into the mountains. He added that the Quechan were planning their own revenge raid.

The Cocopah also formed an alliance with the Paipai and Halyikwamai. Together, they outnumbered the Quechan warriors. Many Quechan warriors gathered at Fort Yuma, which was now a trade center with the Americans. So many warriors at the post worried the soldiers. But the Quechan were not hostile.

When about 250 men were ready, they raided south into Cocopah territory. They killed seven warriors and four women. At the same time, the Mohave, led by Chief Arateve, raided Cocopah territory. The Quechan had asked them to join the war. The Mohave did not want to fight, but they helped their Quechan friends. In the raid, three Cocopah men were killed, and two women were captured. According to the Mohave, years later, the Cocopah women were captured to marry Mohave men. This would help ensure peace between the two tribes by having children who were half Cocopah and half Mohave.

When the conflict with the Cocopah stopped, the Americans at Fort Yuma got a new goal. This was to prevent more fighting between the Native American tribes. Chief Arateve went to Fort Yuma. He asked the Americans to deliver a kind of contract to four other Mohave war chiefs. These four brave men were Kapetame, Asikahota, Tapaikuneche, and Hatsurama. With Arateve, they were known as the "Five Brave Men."

All five chiefs were equal in rank. Each received five letters from the American army. If they accepted, they would no longer attack other Native American tribes or American settlers. They also would not stop the army from building forts and roads on their land. If they did not agree, the United States would go to war against the Mohave. With some convincing from Arateve, the four other chiefs eventually agreed to be peaceful. This brought the Yuma War to an end.

What Happened Next

After the Gadsden Purchase in June 1853, the eastern side of the Colorado River became part of the United States. Even though the war between the Quechan and the Americans was over, the U.S. Army could now launch major military actions across the river. They did not have to worry about the Mexican military.

War between the United States and the Mohave became real in 1858. Mohave warriors attacked American settlers at Beale's Crossing in Arizona. This attack led to the building of Fort Mohave. The war ended in 1859 after the Mohave were defeated twice in two important battles.

Later, the Quechan fought with the Maricopa. In 1857, the last major battle involving the Quechan was fought. This happened at Pima Butte in the Sierra Estrella Mountains. The Maricopa and Pima defeated and killed over 100 Quechan and their allies. After this, the Quechan were no longer a strong military power.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |