Crime and Punishment facts for kids

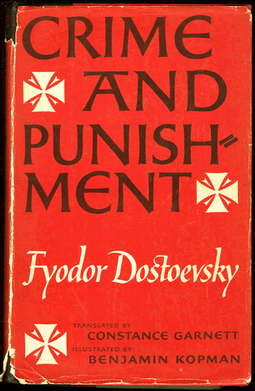

1956 Random House printing of Crime and Punishment, translated by Constance Garnett

|

|

| Author | Fyodor Dostoevsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Преступленіе и наказаніе |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Publisher | The Russian Messenger (series) |

|

Publication date

|

1866; separate edition 1867 |

| OCLC | 26399697 |

| 891.73/3 20 | |

| LC Class | PG3326 .P7 1993 |

| Translation | Crime and Punishment at Wikisource |

Crime and Punishment is a famous novel by the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was first published in a magazine called The Russian Messenger in 1866. Later, it came out as a single book. This novel is seen as one of the greatest books ever written.

The story follows Rodion Raskolnikov, a poor former student in Saint Petersburg. He plans to take money from an old woman who lends money at high interest. Raskolnikov believes that with her money, he could escape poverty and do great things. He tries to convince himself that some bad actions are okay if they help "extraordinary" people achieve bigger goals. But after he acts, he feels confused, worried, and disgusted. His reasons for acting lose all meaning as he struggles with guilt and fear. He faces the difficult results of his actions, both inside his mind and in the real world.

Contents

Discovering the Story's Beginnings

Dostoevsky wrote Crime and Punishment when he needed money. He also wanted to help his brother's family after his brother passed away. He offered his story to Mikhail Katkov, a publisher for a well-known magazine called The Russian Messenger.

In a letter from 1865, Dostoevsky explained that his story would be about a young man with "strange, unfinished ideas." He wanted to explore the dangers of certain extreme ways of thinking. At first, he thought it would be a short story, but it soon grew into a full novel.

At the end of November much had been written and was ready; I burned it all; I can confess that now. I didn't like it myself. A new form, a new plan excited me, and I started all over again.

Dostoevsky worked on different versions of the novel. He first thought about telling the story from Raskolnikov's point of view, like a diary or a confession. But he later decided to tell it from a third-person perspective. This means the narrator knows what all the characters are thinking and feeling. This change allowed Dostoevsky to show Raskolnikov's thoughts and feelings in a new way.

Dostoevsky was under a lot of pressure to finish the novel on time. He was also working on another book at the same time. Anna Snitkina, a stenographer who later became his wife, helped him a lot during this busy period. The first part of Crime and Punishment was published in January 1866, and the last part came out in December 1866.

Main Characters in the Story

Here are some of the important characters in Crime and Punishment:

| Russian and romanization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| First name, nickname | Patronymic | Family name | |

| Родиóн Rodión |

Ромáнович Románovich |

Раскóльников Raskól'nikov |

|

| Авдо́тья Avdótya |

Рома́новна Románovna |

Раско́льникова Raskól'nikova |

|

| Пульхери́я Pulkhería |

Алексáндровна Aleksándrovna |

||

| Семён Semyón |

Заха́рович Zakhárovich |

Мармела́дов Marmeládov |

|

| Со́фья, Со́ня, Со́нечка Sófya, Sónya, Sónechka |

Семёновна Semyónovna |

Мармела́дова Marmeládova |

|

| Катери́на Katerína |

Ива́новна Ivánovna |

||

| Дми́трий Dmítriy |

Проко́фьич Prokófyich |

Вразуми́хин, Разуми́хин Vrazumíkhin, Razumíkhin |

|

| Праско́вья Praskóv'ya |

Па́вловна Pávlovna |

Зарницына Zarnitsyna |

|

| Арка́дий Arkádiy |

Ива́нович Ivánovich |

Свидрига́йлов Svidrigáilov |

|

| Ма́рфа Márfa |

Петро́вна Petróvna |

Свидрига́йлова Svidrigáilova |

|

| Пётр Pyótr |

Петро́вич Petróvich |

Лужин Lúzhyn |

|

| Андре́й Andréy |

Семёнович Semyónovich |

Лебезя́тников Lebezyátnikov |

|

| Порфи́рий Porfíriy |

Петро́вич Petróvich |

||

| Лизаве́та Lizavéta |

Ива́новна Ivánovna |

||

| Алёна Alyóna |

|||

| An acute accent marks the stressed syllable. | |||

How the Novel is Organized

The novel is split into six parts, plus an epilogue at the end. Many people have noticed that Crime and Punishment has a balanced structure. It's almost like the book is split into two mirror halves.

The first three parts show Raskolnikov as mostly logical and proud. The last three parts show him becoming more emotional and humble. The middle of the novel is where his character starts to change. This balance is created by placing similar events in both halves of the book.

The Epilogue, which is the seventh part, has been talked about a lot. Some critics think it's not needed, while others believe it's a very important part of the story.

The Author's Writing Style

Crime and Punishment is told from a third-person point of view. This means the narrator is like an all-knowing observer. The story is mainly seen through Raskolnikov's eyes, but sometimes it switches to other characters like Svidrigaïlov or Sonya. This way of telling a story, where the narrator is very close to the characters' thoughts, was quite new for its time.

Dostoevsky uses different ways of speaking and sentence lengths for his characters. For example, characters who use very formal or fake language, like Luzhin, are often shown as unpleasant. The way Mrs. Marmeladov speaks shows her mind is falling apart.

In the original Russian, many character names have a hidden meaning. For example, the Russian word for "crime" (Prestupléniye) literally means "a stepping across." This suggests that a crime is like crossing a boundary or a line. This deeper meaning is often lost when the book is translated into English.

Different English Versions

Many people have translated Crime and Punishment into English over the years. Here are some of the well-known translations:

- Frederick Whishaw (1885)

- Constance Garnett (1914)

- David Magarshack (1951)

- Princess Alexandra Kropotkin (1953)

- Jessie Coulson (1953)

- Revised by George Gibian (Norton Critical Edition, 3 editions – 1964, 1975, and 1989)

- Michael Scammell (1963)

- Sidney Monas (1968)

- Julius Katzer (1985)

- David McDuff (1991)

- Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (1992)

- Oliver Ready (2014)

- Nicolas Pasternak Slater (2017)

- Michael R. Katz (2017)

- Roger Cockrell (2022)

For many years, the translation by Constance Garnett was the most popular. But since the 1990s, translations by David McDuff and Richard Pevear/Larissa Volokhonsky have become very popular too.

Movies and TV Shows Based on the Book

Crime and Punishment has been made into over 25 movies and TV shows! Here are a few examples:

- Raskolnikow (1923) directed by Robert Wiene

- Crime and Punishment (1935 American film) starring Peter Lorre

- Crime and Punishment (1970 film) a Soviet film

- Crime and Punishment (1979 TV serial) a 1979 TV show by the BBC, starring John Hurt

- Crime and Punishment (1983 film) (original title, Rikos ja Rangaistus), a Finnish movie set in modern-day Helsinki

- Without Compassion (1994 Peruvian film) directed by Francisco Lombardi

- Crime and Punishment in Suburbia (2000), a modern American version

- Crime and Punishment (2002 film), starring Crispin Glover

- Crime and Punishment (2002 TV film) a 2002 TV show by the BBC, starring John Simm

- Crime and Punishment (2007 Russian TV serial) a 2007 Russian TV show

See also

In Spanish: Crimen y castigo para niños

In Spanish: Crimen y castigo para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |