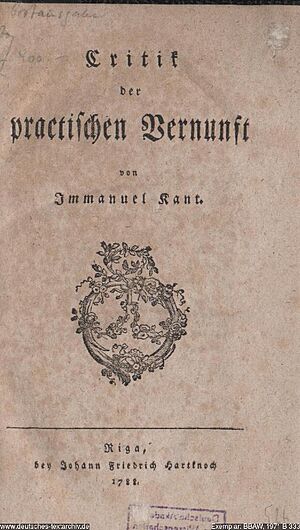

Critique of Practical Reason facts for kids

1788 German edition

|

|

| Author | Immanuel Kant |

|---|---|

| Original title | Critik a der practischen Vernunft |

| Translator | Thomas Kingsmill Abbott |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Moral philosophy |

| Published | 1788 |

| Media type | |

| Preceded by | Critique of Pure Reason |

| Followed by | Critique of Judgment |

| a Kritik in modern German. | |

The Critique of Practical Reason (German: Kritik der praktischen Vernunft) is a famous book by Immanuel Kant. He was a very important German philosopher. This book was published in 1788. It is the second of Kant's three main "critiques." Because of this, people sometimes call it the "second critique."

This book is a major work on moral philosophy. It builds on Kant's first critique, the Critique of Pure Reason. In this book, Kant wanted to explain how our will can be guided by moral rules alone. He also wanted to fit his ideas about right and wrong into his larger philosophy. He explored ideas like respecting moral laws and the idea of the "highest good."

Contents

What is this Book About?

Kant didn't originally plan to write a separate book just about practical reason. He first wrote the Critique of Pure Reason in 1781. That book looked at how human reason works in general. It was meant to prepare for understanding both nature and morals.

Later, Kant started writing about morals. He wrote the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals in 1785. In that book, he began to think that a deep understanding of morals needed its own "critique." He felt that human reason could understand moral matters quite well on its own.

Kant then thought about adding this work as an appendix to his first critique. This was to answer some criticisms. But he changed his mind again. Finally, in 1787, he sent the finished book to be printed. It was officially published in 1788.

How the Book is Organized

The Critique of Practical Reason is structured like Kant's earlier book. It starts with a preface and an introduction. Then it has two main parts:

- The Doctrine of Elements

- The Doctrine of Method

The Doctrine of Elements is further divided into two sections:

- The Analytic of pure practical reason

- The Dialectic of pure practical reason

The Analytic explains Kant's ideas about how we make moral choices. It looks at the rules of morality. It shows that pure reason can guide our actions. This means reason can make us act without being influenced by our feelings or desires. It also discusses what the goal of pure practical reason is, which is "the good."

The Dialectic deals with common mistakes people make when thinking about practical reason. It talks about ideas like the "highest good." It also explains how the ideas of God and the soul's immortality fit into our moral thinking. Kant calls these "postulates of practical reason."

The Doctrine of Method is about moral education. It explores how we can help people understand and follow moral laws in their daily lives.

Parts of the Critique of Practical Reason

Preface Introduction

- Part I. Doctrine of the Elements of Pure Practical Reason

- Book I. Analytic of Pure Practical Reason

- Chapter I. On the Principles of Pure Practical Reason

- §1. Explication (explaining practical principles)

- §2–4. Theorems I-III

- §5–6. Problems I & II

- §7. Basic Law of Pure Practical Reason (the Categorical imperative)

- §8. Theorem IV

- a. Practical Material Determining Bases (why old ideas about morality were wrong)

- I. On the Deduction of the Principles of Pure Practical Reason

- II. On the Authority of Pure Reason in Its Practical Use to an Expansion That Is Not Possible for It in Its Speculative Use

- Chapter II. On the Concept of an Object of Pure Practical Reason

- a. Table of the Categories of Freedom in Regard to the Concepts of Good and Evil

- b. Typic of the Pure Practical Power of Judgment

- Chapter III. On the Incentives of Pure Practical Reason

- a. Critical Examination of the Analytic of Pure Practical Reason (comparing it to the Critique of Pure Reason)

- Chapter I. On the Principles of Pure Practical Reason

- Book II. Dialectic of Pure Practical Reason

- Chapter I. On a Dialectic of Pure Practical Reason as Such

- Chapter II. On a Dialectic of Pure Reason in Determining the Concept of the Highest Good

- I–II. Antinomy of Practical Reason & its Critical Annulment

- III. On the Primacy of Pure Practical Reason in Its Linkage with Speculative Reason

- IV-V. The Immortality of the Soul & God's Existence, as Postulates of Pure Practical Reason

- VI. On the Postulates of Pure Practical Reason as Such

- VII. How It Is Possible to Think an Expansion of Pure Reason for a Practical Aim without Thereby Also Expanding Its Cognition as Speculative

- VIII. On Assent from a Need of Pure Reason

- IX. On the Wisely Commensurate Proportion of the Human Being's Cognitive Powers to His Practical Vocation

- Book I. Analytic of Pure Practical Reason

- Part II. Doctrine of the Method of Pure Practical Reason

Conclusion

Preface and Introduction

In these first sections, Kant explains what the book will cover. He often compares theoretical reason (how we think about facts) with practical reason (how we decide what to do).

His first critique, Critique of Pure Reason, criticized people who claimed to know deep truths about the world using only theoretical reason. It concluded that theoretical reason has limits. But the Critique of Practical Reason is different. It defends pure practical reason. It argues that this kind of reason can guide our actions better than just following our desires.

Kant also mentions that his first critique said we couldn't truly know about God, freedom, or immortality. But this second critique says we can understand them through practical reason. Freedom is shown by our ability to follow moral laws. God and immortality become things we must believe in for practical reasons. Kant challenges anyone to prove God's existence in a different way, saying it's not possible.

He says this book can be understood on its own. It also answers some criticisms of his earlier work, the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Kant believes many criticisms come from people not fully understanding his ideas. He promises this second critique will be easier to read than the first.

Analytic: Chapter One

Practical reason helps us decide what to do. It works by using a general rule for action in a specific situation. For Kant, a "practical principle" can be a "maxim" if it's based on what someone wants. But it's a "law" if it applies to everyone.

Any rule that depends on a person's desires can't be a universal law. This is because desires are different for everyone. So, a rule like "always seek the greatest happiness" can't be a universal moral law. This is because it depends on someone wanting happiness.

Kant says that a universal moral law gets its power not from its content, but from its form. The moral law, called the categorical imperative, is about its universal form. It means:

Act in such a way that the maxim of your will could always hold at the same time as a principle of a universal legislation.

This means, act only on rules you'd want everyone to follow.

Kant argues that a will following this moral law is free. It's not controlled by senses or desires. It's independent of the world of senses. If the will is free, it must follow a rule. This rule's content shouldn't limit its freedom. The categorical imperative is the only rule like this. Following the practical law means you are autonomous (self-governing). Following rules based on desires means you are heteronomous (governed by others or outside forces).

Kant then looks at six old moral ideas. He says they all fail. They try to base morality on things like happiness or perfection. But this makes them depend on desires, which isn't truly free or universal.

He also says we know we are free because we feel the moral law working on us. Even though we often act out of "self-love," we know we can ignore our desires when duty calls. This feeling of the moral law is something we know without needing experience.

Analytic: Chapter Two

Kant explains that for practical reason, every action aims to create something in the world. But for pure practical reason, the goal is something that can be achieved by simply willing the right action. This is true no matter what our personal desires are. The only possible goal for the practical law is "the Good."

It's important not to confuse "the Good" with just seeking pleasure. If we understand "the Good" as just pleasure, then morality becomes about feeling good. But "good" in a moral sense is different from "well-being." A good person might suffer, but they are still good. A bad person might suffer punishment, which is painful for them, but it's morally good and just.

Past philosophers often made this mistake. They tried to define morality based on what is good, instead of defining what is good based on morality. This led them to confuse pleasure with what is morally right.

Kant believes the moral law is the same as the idea of freedom. We can't see what is morally right. We can only know it by thinking if an action we want to do could be done by everyone. Kant calls this idea "moral rationalism." This is different from "moral empiricism," which says we learn right and wrong from the world. It's also different from "moral mysticism," which says morality is about sensing something supernatural. Kant thinks moral empiricism is especially harmful. It makes morality seem like it's just about seeking pleasure.

Kant's view is that following the categorical imperative is the most important part of ethics. It's about having the right motivations – acting out of duty. This means Kant is a deontologist. This word means someone who believes duty is the main thing in ethics. Because of this, Kant says we can never be completely sure if an action was truly moral. This is because the moral rightness comes from the will's hidden reasons, which we can't fully know.

Analytic: Chapter Three

To act morally, you must be directly motivated by the moral law itself. If someone does the right thing, but only because it feels good or for some other reason, their action has "legality" but not "morality." For Kant, moral actions must be done because of the moral law. An "incentive" is what makes a person act when their reason doesn't always follow the moral law.

A free will must act only from the moral law. It must even ignore desires that go against the law. We naturally tend to be selfish and seek pleasure. We also tend to be self-centered, thinking we deserve whatever we want. The moral law limits this selfishness. It makes us realize we are not above the moral law. This makes us feel respect for the moral law. This feeling doesn't come from our senses. It comes from pure reason, from knowing the moral law is true.

Kant finishes this chapter by comparing the structure of this book to his first critique. He notes that the first critique started with senses, then concepts, then principles. This book, however, starts with principles for moral action. Then it moves to concepts (like good and evil). Finally, it looks at how pure practical reason relates to our feelings, like respect for the moral law.

Dialectic: Chapter One

Pure reason, both in how we think and how we act, always looks for something "unconditional." This means something that doesn't depend on anything else. But in the world we experience, everything depends on something else. Kant says the unconditional can only be found in a deeper, non-physical world. When pure theoretical reason tries to reach this unconditional world, it fails. This leads to "antinomies," which are two conflicting statements that both seem true.

In this book, Kant finds an antinomy for pure practical reason. This antinomy is about the "highest good." The highest good is the goal of pure practical reason. Good actions seem to depend on this highest good to be worthwhile. But believing in a highest good leads to problems, and not believing in it also leads to problems.

Dialectic: Chapter Two

Kant talks about two meanings of "the highest good." One meaning is the "supreme" good. This is something that is always good and needed for all other good things. This is like "dutifulness." The other meaning is the "perfect" good. This is the best possible state, combining being good (virtue) with being happy.

The highest good is the goal of pure practical reason. We need to believe it's possible to achieve it. But in this world, being virtuous doesn't always make you happy, and vice versa. It seems like luck if you get rewarded for being good.

Kant's solution is that we exist not just in the physical world, but also in a deeper, non-physical world. Even if we aren't rewarded with happiness here, we might be in an afterlife. This afterlife is something pure practical reason needs us to believe in. So, immortality and union with God become necessary beliefs for reason.

The highest good needs the highest level of virtue. We know we aren't perfectly virtuous now. The only way to become truly virtuous is to take an eternity to reach perfection. So, we can believe in immortality. This helps us imagine how we could become perfectly moral. If we don't believe this, we might either lower moral demands or try to be perfect instantly, which is impossible.

The highest good also needs the highest level of happiness to reward the highest virtue. So, we need to believe in an all-knowing and all-powerful God. This God can make the world fair and reward us for our virtue. But this doesn't mean God is the reason we act morally. Instead, believing in God helps us understand how the highest happiness could be possible for the highest virtue.

Doctrine of Method

In his first critique, the Doctrine of Method was about studying theoretical reason. Here, it's about how we can use practical reason in real life. It's mainly about moral education: how to help people live and act morally.

Kant has shown that true moral behavior needs more than just acting good on the outside. It also needs the right inner reasons. Some people might doubt if humans can truly act out of "obligation to duty." They might think society is just a show of morality, with everyone secretly looking out for themselves. But Kant believes these doubts are wrong.

When people gather, they often gossip and judge others' actions. Even those who don't like complex arguments become very focused when discussing if their neighbors' behavior is right or wrong.

Moral education should use this natural human tendency. It should present students with real-life examples of good and bad actions. By discussing these examples, students can feel the admiration for moral goodness and disapproval for moral evil.

However, it's important to choose the right examples. Kant says we can make two mistakes. First, don't try to make students moral by showing examples where being moral also benefits them. Second, don't try to excite students with examples of extreme heroism. Instead, choose examples that show simple dutifulness.

The first method fails because students won't learn that duty is unconditional. These examples also aren't inspiring. We are more impressed by great sacrifice for a principle than by someone following a rule with no cost.

The second method also fails because it appeals to emotions, not reason. Only reason can create lasting change in a person. This method also makes morality seem like a dramatic show, making everyday duties seem boring.

Kant ends the book on a hopeful note. The wonders of the physical world (like the stars) and the moral world (the moral law within us) are always there to inspire awe. He hopes that just as physical sciences replaced old superstitions, moral sciences will soon bring true knowledge to ethics.

Influence

The Critique of Practical Reason greatly influenced how people thought about ethics and moral philosophy. It started with Johann Gottlieb Fichte's Doctrine of Science. Fichte felt that reading Kant's book in 1790 helped him solve his own philosophical problems. He wrote that ideas he thought were unbreakable had been overturned. He was happy that concepts like absolute freedom and duty had been proven to him. Later, in the 20th century, this book became a key text for deontological moral philosophy and Kantian ethics.

English Translations

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of practical reason. In Practical Philosophy. Edited and translated by Mary J. Gregor. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN: 9780521654081.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |