Danum shield facts for kids

The Danum shield was a Roman shield found in 1971. It was discovered at the Danum Roman fort in Doncaster, England. This shield was found among the remains of a bonfire. It might have been thrown away on purpose when part of the fort was left empty.

The shield was shaped like a rectangle. It was about 0.65 meters (2.1 feet) wide and 1.25 meters (4.1 feet) long. Experts believe it belonged to a Roman auxilium soldier. These were soldiers who were not full Roman citizens.

At first, people thought the shield had a rare vertical hand grip. This suggested it might have been used by cavalry (soldiers on horseback). However, newer ideas suggest the hand grip was horizontal. This would mean it was used by an infantryman (a soldier who fights on foot). The shield was covered in leather and was probably painted. We don't know its original color. Its outer surface had bronze decorations. These might have had Celtic patterns carved into them.

Today, the iron parts of the shield, like the boss (the round metal bump in the middle) and handgrip, are on display. You can see them at the Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery. A copy of the shield, made in 1978, is also there. The exhibit moved to the new Danum Gallery, Library and Museum in 2020.

Contents

Finding the Shield

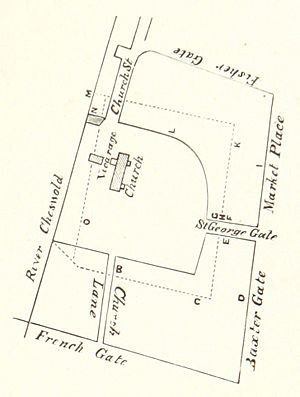

The Danum shield was found in 1971. This happened during digs near St George's Minster, Doncaster. These excavations were exploring the city's Roman fort, Danum. They were done before a new road, the Inner Ring Road, was built.

The Danum fort was built and used as early as 69–79 AD. But it was left empty when the Roman army went to fight in Caledonia (modern Scotland). This happened under the orders of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, a Roman governor. The Romans seemed to have carefully taken down parts of the fort when they left.

After 87 AD, the fort was rebuilt in the same spot. It was made bigger for more soldiers. These soldiers had come back from Caledonia. This timber (wood) fort was later replaced by a stone fort. This happened during the Antonine era.

During the excavations, archaeologists dug through one of the stone fort's walls. They found that much of the 2-meter (6.6-foot) wall had been destroyed. This was due to a medieval cellar built later. Evidence showed this spot was near one of the old wooden fort's roads.

Under the cellar floor, a thin layer was found. It was only a few centimeters (about one inch) thick. This layer was the remains of a bonfire. It might have been linked to the fort being abandoned. The Danum shield's remains were found near the edge of this bonfire layer. It was lying face down.

The iron boss and hand grip were noticed first. More digging showed the full shield. It was partly turned to charcoal. The remains had been slightly disturbed by a later trench and an animal run. The charcoal helped preserve details of the shield's wood layers. It also showed a black, glassy material. This was thought to be the remains of its leather outer covering.

The shield was too fragile to dig up by hand. So, it was lifted in one big block. This block was covered in plaster and weighed about 30 long hundredweight (1,524 kg). This block was then studied in London by Leo Biek.

What the Shield Looked Like

Fewer than ten Roman shields have been found by archaeologists. This makes the Danum shield a very important discovery. The Danum shield is from the late 1st century or early 2nd century. It is believed to have belonged to a Roman auxiliary soldier. However, because these soldiers had different equipment, this isn't completely certain.

Archaeologist Paul Buckland shared his study of the shield in 1978. His work was based on the original dig and later studies.

Buckland's Ideas (1978)

Buckland believed the shield's main board was mostly rectangular. It had curved top and bottom edges. It was about 0.64 meters (2.1 feet) wide and 1.25 meters (4.1 feet) long. The board was about 10 millimeters (0.4 inches) thick. This was based on the size of the iron rivets used.

The shield was flat, not curved like the famous Roman scutum shield. The board was made from three layers of wood. The middle layer was oak, and the outer layers were alder. They were joined with glue. The middle layer had six pieces of wood, about 3.8 millimeters (0.15 inches) thick. These were placed vertically. The outer layers had pieces about 3.2 millimeters (0.13 inches) thick. These were placed horizontally. The pieces of wood varied in width, from 103 to 110 millimeters (4.1 to 4.3 inches).

The shield's edge was not covered in iron bands. Some other Roman shields had this feature. Without iron bands, the shield would be less strong against slashing weapons like swords. Perhaps this design was meant to trap an enemy's sword. Or maybe the shield was only for fighting opponents with spears.

The domed shield boss was 200 millimeters (7.9 inches) across. It was made of 2-millimeter (0.08-inch) thick iron. It was placed 50 millimeters (2 inches) above the shield's center. It was attached with four iron rivets. These went through a 28-millimeter (1.1-inch) wide edge. The boss being off-center would make the bottom of the shield tilt. This would help protect the soldier's legs.

On the back of the shield was an 0.8-meter (2.6-foot) vertical iron hand grip. It was held by six iron rivets. On the front, a wooden rib called a spina hid these rivets. This spina was 28–33 millimeters (1.1–1.3 inches) wide and 5 millimeters (0.2 inches) thick. It ran vertically down the shield's center. It didn't add to the shield's strength. The handgrip showed signs of being repaired. This might have been because it broke or the rivets came out. The spina was removed, the grip was reattached with nails, and then the spina was put back.

Tiny pieces showed that the center of the grip was wrapped in leather. This is where the soldier would hold it. When the shield burned, the boss and grip sprang away. They took some wood with them. The boss was not very deep. This would leave the soldier's hand open to hits. It's possible that horse-hair padding was used, like on another shield found at Caerhun.

The boss showed signs that someone tried to remove it. This happened before the shield was burned and thrown away. They might have wanted to reuse it. A leather strap might have connected the grip to the soldier's wrist. This would help spread the shield's weight. It would also stop the shield from being lost in battle. An iron ring was found on the handgrip. With an eyelet on the back of the shield, it might have held a leather shoulder strap for carrying.

There was evidence of a leather cover on both sides of the shield. This cover might have been made from a single cow hide. It was probably painted, but no color remains were found. The leather cover had decorative lines of iron studs. These studs were about 10 millimeters (0.4 inches) across. They stuck out about 6 millimeters (0.2 inches). One line of studs went out from the boss. Similar lines were probably on all four parts of the shield. Other studs were found in a 60-millimeter (2.4-inch) long crescent shape. This was 70 millimeters (2.8 inches) from the bottom of the shield. A similar group was probably at the top. These studs likely didn't help much with tightening the leather cover. The leather was probably glued to the wood. But the studs might have helped keep the wood layers together.

The rivets through the handgrip had small pieces of bronze sheeting. This bronze probably decorated the shield's front. Most of the bronze seems to have been removed before the shield was thrown away. We can't know the exact pattern. But green rust left in the sand gives some clues. The bronze sheeting was held by small bronze studs. These were 5 millimeters (0.2 inches) and 8 millimeters (0.3 inches) wide. They had flat and domed heads. At least four studs went out from the boss. They were extensions of the iron stud lines. The bronze might have had a carved pattern of curves and lines. This would be in a Celtic style. It might have been used to tell different groups apart in battle.

The vertical grip on this shield is rare for Roman finds. Most others have horizontal grips. Two other shields are similar to the Danum one. One was found at Trimontium fort in Scotland. The other was near Strasbourg, France. A vertical grip would be hard for an infantryman to use. It's harder to push force through the shield with a vertical grip. This is important in close combat. Buckland thought the shield might have been used by a Roman cavalryman. But he noted it was heavier than other known cavalry shields. Those were mostly made of leather.

Buckland also thought the shield might not have been Roman. It could have been a prize taken from a Gallic tribe. It looks a bit like shields from European Iron Age tribes. However, Buckland said the number and placement of rivets suggested it was Roman. It might have been brought by an auxiliary soldier from Western Europe. Buckland believed the shield was likely thrown away in the early 2nd century AD. This might have been around 105 AD. That's when the Roman army left Caledonia.

New Ideas from Travis & Travis (2014)

Hilary and John Travis talked about the Danum shield in their 2014 book, Roman Shields. They suggested that Buckland's findings could be seen in a new way. The handgrip came off when the shield burned. So, it's possible it was originally horizontal. This would make it better for infantry soldiers.

For this idea to be true, the shield would need two layers of wood. The inner layer would be vertical, and the outer layer horizontal. Travis & Travis suggest the shield would still be 10 millimeters (0.4 inches) thick. Each layer would be about 5 millimeters (0.2 inches) thick. This is different from Buckland's idea of three thinner layers. A horizontal handgrip would match shields found at Faiyum Oasis and Dura-Europos. It would also match six other iron handgrips found elsewhere.

Travis & Travis also suggested the shield might have been curved. This is like the more common Roman shields. It might have flattened out after being in the fire. A horizontal handgrip would be more likely to spring away from a curved shield in a fire. Buckland himself first thought the shield was curved during the 1971 dig. Travis & Travis also believe that if the shield was thrown away on purpose, the handgrip and boss would have been saved. They suggest the shield might have accidentally burned in the fire.

Where to See It

The boss and handgrip from the shield were saved. Some iron and bronze pieces were also kept. They have been on display at the Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery. Buckland made a "reasonably accurate" copy of the shield in 1978. This copy has been shown next to the real pieces. The copy was inspired by a shield shown on the Triumphal Arch of Orange. The bronze decoration at the top was based on findings from a Roman camp at Vindonissa. The copy weighs about 9 kilograms (20 pounds). This is probably a bit lighter than the original shield.

The shield remains were moved to the Danum Gallery, Library and Museum in 2020.