Deepwater Horizon oil spill response facts for kids

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill happened in the Gulf of Mexico from April to September 2010. This huge oil spill needed many different ways to clean it up. The main goals were to keep the oil from spreading on the surface, break it up with chemicals, and remove it from the water. The oil that leaked was a heavy type, almost like asphalt. This kind of oil mixes easily with water, forming a thick mixture called an emulsion. Once it becomes an emulsion, it doesn't evaporate quickly, is hard to wash off, and is tougher for tiny living things (microbes) to break down. It also doesn't burn well. Experts said this type of oil made the cleanup much harder.

BP, the company responsible, started sharing daily updates on their website in May 2010. The US military joined the cleanup in April. As the spill grew, so did the cleanup effort. At first, BP used underwater robots, 700 workers, 4 airplanes, and 32 boats. Soon, 69 boats were helping, including special oil-skimming vessels. By May 2010, about 170 boats and nearly 7,500 people were working on the cleanup, with 2,000 more volunteers. BP even set up a phone line for cleanup ideas, getting 92,000 suggestions! By summer 2010, around 47,000 people and 7,000 boats were involved. The cleanup cost BP over $14 billion by January 2013.

Contents

Stopping the Oil: Containment Efforts

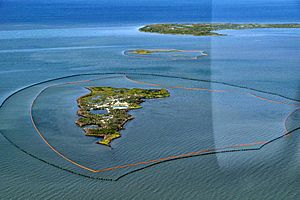

One main way to stop the oil was by using many miles of containment booms. These are floating barriers that either gather the oil or block it from reaching sensitive areas like marshes, mangroves, or places where shrimp and oysters live. Booms usually stick out about 18 to 48 inches (0.45 to 1.2 meters) above and below the water. They work best in calm, slow-moving water.

At first, over 100,000 feet (30 kilometers) of booms were put out to protect the coast and the Mississippi River Delta. This quickly grew to 180,000 feet (55 kilometers) the next day. In total, over 9 million feet (2,700 kilometers) of special oil-absorbing booms and 4 million feet (1,280 kilometers) of containment booms were used during the crisis.

However, some people questioned how well the booms worked. They said there weren't enough booms, and they weren't always put in correctly. Local officials mentioned that the booms would sometimes wash ashore with the oil, creating more problems. Experts noted that strong winds and currents in the Gulf often made the lightweight booms useless. Some estimated that 70% or 80% of the booms weren't doing anything at all. BP itself stated that booms aren't effective in waves higher than three to four feet, which is common in the Gulf.

Building Sand Barriers: Louisiana's Plan

Louisiana started a project called the Louisiana barrier island plan. The idea was to build sand islands in the Gulf of Mexico to protect the coast from the oil spill. In May 2010, the state got an emergency permit to start building these barriers.

The plan was to build berms (raised banks of sand) that were 325 feet (99 meters) wide at the bottom and 25 feet (7.6 meters) wide at the top, rising 6 feet (1.8 meters) above the water. If fully built, these barriers would have been 128 miles (206 kilometers) long. The federal government allowed 45 miles (72 kilometers) to be built. BP agreed to pay the first $360 million for the project.

Some people criticized the plan, saying it would be too expensive and not very effective. They pointed out that it would need a lot of sand and take six months to build. There were also worries about how long the barriers would last against normal waves and storms. Critics suggested the decision to build them was political, without much advice from scientists.

Even after the oil well was capped in July 2010, construction of the berms continued. BP paid for the project, and the Army Corps of Engineers oversaw it. By October 2010, there was growing opposition to the project. A presidential report in December 2010 concluded that the $220 million sand berms only caught a "tiny amount" of oil and were "overwhelmingly expensive" for how little they did. Louisiana later planned to use $140 million of the remaining money to turn the completed berms into artificial barrier islands by making them wider and adding plants.

Breaking Up the Oil: Dispersants

The Deepwater Horizon spill also used a lot of oil dispersant chemicals, especially a product called Corexit. This was done in ways that had never been tried before. Dispersants are chemicals that break oil into tiny droplets, making it mix with water. This can help reduce the amount of oil on the surface and protect shorelines. However, the use of dispersants was questioned, and their effects are still being studied. In total, about 1.84 million US gallons (7 million liters) of dispersants were used. A large amount of this (771,000 US gallons or 2.9 million liters) was sprayed directly at the wellhead deep underwater.

What is Corexit?

The main dispersants used were Corexit EC9500A and Corexit EC9527A. These weren't the least toxic or most effective options on the EPA's approved list. Twelve other products had better safety and effectiveness ratings. BP said they chose Corexit because it was available quickly after the explosion. However, some critics believed that major oil companies keep Corexit on hand because of their close ties with its maker, Nalco.

Environmental groups tried to find out what chemicals were in Corexit, but the information was kept secret at first. After a lawsuit, the EPA released a list of chemicals in various dispersants. Corexit contains chemicals like propylene glycol and 2-butoxyethanol. A study in 2011 looked at the chemicals in Corexit and found that some were linked to health concerns like skin and eye irritation, breathing problems, and potential harm to aquatic life.

How Dispersants Were Used

Over 400 flights sprayed dispersants over the oil spill. In May 2010, four military C-130 Hercules planes, usually used for spraying pesticides, were sent to the Gulf to spray dispersants. More than half of the dispersants were applied 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) under the sea, directly at the wellhead. This had never been done before. BP, along with the US Coast Guard and the EPA, decided to try this because the spill was so big and unusual.

The idea behind using dispersants deep underwater was to break up the oil before it reached the surface. This would allow tiny microbes to eat the oil. One concern was that increased microbe activity might use up too much oxygen in the water. NOAA estimated that about 409,000 barrels (65 million liters) of oil were dispersed underwater.

By July 2010, BP reported using over 1 million US gallons (3.8 million liters) of Corexit on the surface and 721,000 US gallons (2.7 million liters) underwater. By the end of July, over 1.8 million US gallons (6.8 million liters) had been used. BP said they stopped using dispersants after the well was capped. However, some independent tests and eyewitness accounts suggested that dispersants were still being used near the coast even later.

Long-Term Effects of Corexit

NOAA stated that tests suggested the mix of dispersant and oil was no more toxic than oil alone. However, some experts believe the full effects might not be known for many years. A study in late 2012 found that Corexit made the oil up to 52 times more toxic than oil by itself. It also made the oil sink faster and deeper into beaches and possibly groundwater.

Scientists from the University of South Florida found that tiny oil droplets mixed with dispersants might be more toxic than thought. They saw that this dispersed oil seemed to harm bacteria and phytoplankton, which are tiny plants that form the base of the Gulf's food web.

Because dispersants were used deep underwater, much of the oil never reached the surface. This means it went somewhere else. Experts say dispersants don't make oil disappear; they just move it. One plume of dispersed oil was found to be 22 miles (35 kilometers) long, over a mile (1.6 kilometers) wide, and 650 feet (200 meters) thick. Researchers found this oil was staying around longer than expected and wasn't breaking down quickly in the cold, deep water. Another study found a thick layer of oily sediment stretching for dozens of miles around the capped well.

Getting Rid of the Oil: Removal Methods

There were three main ways to remove oil from the water: burning it, skimming it off the surface, and collecting it for processing. In April 2010, the US Coast Guard planned to gather and burn up to 1,000 barrels (159,000 liters) of oil each day. By November 2010, reports said that controlled burning removed as much as 13 million US gallons (49 million liters) of oil from the water. There were 411 fires set between April and mid-July 2010. The EPA stated that any harmful chemicals released from these fires were minimal.

Oil was also collected using special boats called skimmers. More than 60 skimmers were used. A very large Taiwanese ship called the A Whale was changed to skim huge amounts of oil. However, tests in July 2010 showed it didn't collect much oil. A spokesperson for the ship's owner said that BP's use of Corexit had spread the oil too much for the skimmer to collect it effectively.

BP also ordered 32 machines that could separate oil and water. Each machine could extract up to 2,000 barrels (318,000 liters) of oil per day. After testing, BP decided to use this technology. By June 28, they had removed 890,000 barrels (141 million liters) of oily liquid. The US Coast Guard reported that 33 million US gallons (125 million liters) of tainted water were recovered, with 5 million US gallons (19 million liters) of that being oil.

Where Did the Oil Go? The Oil Budget

NOAA created an "oil budget" to estimate what happened to the oil from the spill. They estimated that about 4.9 million barrels (779 million liters) of oil were released. The table below shows how they thought the oil was dealt with. "Chemically dispersed" means oil broken up by chemicals, and "naturally dispersed" means oil that broke up on its own. "Residual" is the oil that remained as a film on the surface, floating tarballs, or oil on shorelines and buried in sediment. There was about a 10% uncertainty in these numbers.

| Category | Estimate |

|---|---|

| Directly recovered from the wellhead | 17% |

| Burned at the surface | 5% |

| Skimmed from the surface | 3% |

| Chemically dispersed | 8% |

| Naturally dispersed | 16% |

| Evaporated or dissolved | 25% |

| Left behind (residual) | 26% |

Two months after these numbers were released, a White House official said they were "never meant to be a precise tool." They explained that the data wasn't designed to show exactly where all the oil went. Oil listed as "dispersed," "dissolved," or "evaporated" wasn't necessarily gone.

Many scientists believed that up to 75% of the oil from the spill might still be in the Gulf environment. They argued that terms like "dispersed" or "dissolved" don't mean the oil disappeared. It's like sugar dissolving in coffee – you can't see it, but it's still there. They warned that oil buried under beaches or on the ocean floor could remain harmful for decades.

NOAA faced criticism for its report, with some scientists saying it wasn't truly scientific and gave the public a false sense of security. They argued that the "imprint" of the oil would be in the Gulf for a very long time.

By late July, two weeks after the oil flow stopped, most of the oil on the surface of the Gulf had disappeared. However, concerns remained about oil underwater and the long-term damage to the environment. One expert, Markus Huettel, believes that at least 60% of BP's oil is still unaccounted for. He stressed that only the 17% directly recovered from the wellhead is truly known, and other categories are just guesses. He said that some oil is "somewhere, but nobody knows where, and nobody knows how much has settled on the seafloor."

Tiny Helpers: Oil-Eating Microbes

Several studies suggested that bacteria in the sea helped to eat some of the oil. In August 2010, a study found a new type of bacteria that could break down oil without using up too much oxygen. However, some experts were skeptical, saying that these microbes might only be breaking down certain parts of the oil, while other parts could last for years or decades. They also noted that large oil plumes were still present and didn't seem to be breaking down very fast.

By mid-September, research showed that these microbes mainly ate natural gas (like propane and butane) that was leaking from the well, rather than the oil itself. Some experts suggested that the idea of oil-eating microbes helping a lot was exaggerated.

Some experts also wondered if the oil-eating bacteria might have caused health issues for people living near the Gulf. Local doctors noticed an increase in skin rashes. Some marine toxicologists suggested these rashes could be linked to the growth of these bacteria in the Gulf waters. People reported symptoms like rashes and "peeling palms" after touching the water.

Final Cleanup Efforts

In April 2014, BP announced that the cleanup along the coast was mostly finished. However, the United States Coast Guard disagreed, stating that a lot of work still needed to be done.

|