Delores S. Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Delores S. Williams

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 17, 1934 |

| Died | November 17, 2022 |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Delores Seneva Williams |

| Alma mater | Union Theological Seminary |

|

Notable work

|

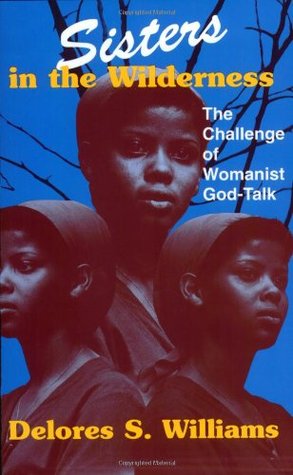

Sisters in the Wilderness (1993) |

| Spouse(s) | Robert C. Williams |

| Children | Rita Williams, Celeste Williams, Steven Williams, Leslie Williams |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Union Theological Seminary |

| Thesis | A Study of the Analogous Relation Between African-American Women's Experience and Hagar's Experience (1990) |

| Doctoral advisor | Tom F. Driver |

| Influences |

|

| Influenced | Ada María Isasi-Díaz |

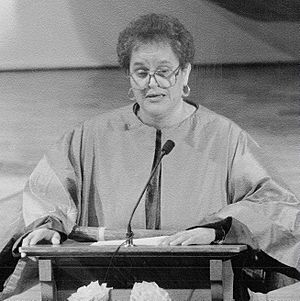

Delores Seneva Williams (November 17, 1937 – November 17, 2022) was an American Presbyterian thinker. She was very important in creating a field of study called womanist theology. She is best known for her book Sisters in the Wilderness. Her writings explored how being black, a woman, and sometimes poor, affected black women's lives.

Unlike feminist theology, which was mostly by white women, and black theology, which was mostly by black men, Williams showed that black women's experiences added a deeper understanding to the idea of unfair treatment in religion. Her book Sisters in the Wilderness helped start the field of womanist theology. In it, Williams looked closely at the Bible story of Hagar. She used Hagar's story to explain how black women were treated, especially when it came to having children or caring for others' children.

The word womanism was first used by Alice Walker, who was also a writer and friend of Williams. Walker used the term in her 1979 short story "Coming Apart" and again in her 1983 book In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens.

Biography

Delores Williams earned her PhD from Union Theological Seminary. Later, she became a professor there. Her title was first Paul Tillich Professor of Feminist Theology. It was later changed to Paul Tillich Professor of Theology and Culture. After she retired, she became Professor Emerita.

Williams' writings were key in developing the field of Womanist Theology. In 1977, she wrote an article called "Womanist Theology: Black Women's Voices." This article was a very important step in the growth of this field. She published her main book, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk, in 1993.

Williams also wrote many other articles and chapters in books. For example, she wrote the eighth chapter of Transforming the Faiths of our Fathers: Women who Changed American Religion (2004). This book was put together by Ann Braude.

What is Womanism?

The idea of Womanism grew out of Black Feminism. It was a term created by Alice Walker. Delores S. Williams noticed that Womanism and Black Feminism were connected to white feminism. However, she also saw that most white feminist movements often did not include the experiences and concerns of black feminists and womanists.

Some white women wanted to challenge unfair treatment more deeply, including issues of race. But many white women, and the most common ideas of feminism, focused on being equal to white men. For black women, equality meant not only ending racism and classism, which feminism didn't always address. It also meant rethinking what equality truly meant, instead of just trying to be like white men.

Womanism is a way of thinking that focuses on the special and unique experiences of black women. Its goal is to find ways of thinking and ideas that fit their lives. The womanist movement wanted to end unfairness. It also aimed to help black women reconnect with their religious and cultural roots. It encouraged them to think about and improve themselves, their communities, and society.

Sisters in the Wilderness

In 1993, Williams published her important book, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk. In this book, Williams starts by looking at the struggles of black women. She then explores ideas from the Bible story of Hagar in the wilderness. The Bible character Hagar was a servant to Abraham and his wife Sarah. Hagar also had Abraham's child, Ishmael, when Sarah and Abraham could not have children.

Williams saw similarities between Hagar's role and the role of black women. Black women often cared for white children during and after slavery. The Bible story of Hagar surviving in the wilderness has inspired many black women. They found strength to survive tough times by relying on their faith.

Williams especially noted how Hagar's situation compared to black women's roles as mothers. This was true both within their own families and in relation to white women. She explained that slavery forced enslaved mothers to protect, provide for, and fight for their loved ones. Yet, like Hagar, many black women were forced to have children for white families or care for their masters' children. After slavery, they often worked for low wages in white people's homes.

In the second part of the book, Williams shows how the womanist view offers special insights into theology. Williams argued that black women's experiences had been ignored in theology. This included black liberation theology and white feminist theology. She believed that womanist theology, by focusing on black women's experiences, offered an important correction. She wrote that it helps "poor, oppressed black women and men to hear and see the doing of the good news in a way that is meaningful for their lives."

Talking with Other Theologies

Williams believed it was important for womanists to talk with feminists. She also supported discussions between womanists and black liberationists, Asian feminist theologians, and mujerista theologians. She felt this could lead to a greater good for everyone. She knew that talking alone wouldn't end racism or sexism. But Williams found that sharing ideas was important. This is because "all women regardless of race or class, have developed survival strategies that have helped [them to] arrive sane at [their] present social and cultural locations."

She noted that there had been little sharing of stories about these survival strategies among women. In the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, she said: "we feminist-womanist women need to remember, commemorate, and lift up for ourselves and subsequent generations of women the resistance events and ideas that have birthed and kept alive women’s rights struggle...create resistant rituals that can be enacted wherever feminist and womanist meet to share survival strategies and plan attacks upon patriarchal and white supremacist mind-sets and practices in American institutional life." By sharing stories of how they survived, women can create new ways to resist unfairness.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |