Demobilization of United States armed forces after World War II facts for kids

After World War II ended, the United States military had a huge job: bringing millions of soldiers, sailors, and airmen home. This process was called demobilization. It started in May 1945, right after Germany was defeated, and continued through 1946.

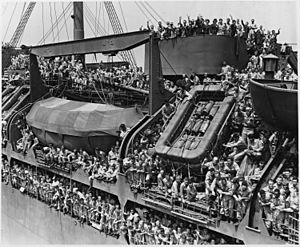

At the end of the war, over 12 million American men and women were serving in the armed forces. About 7.6 million of them were stationed in other countries. Everyone back home wanted their loved ones to return quickly. Soldiers also protested if the process seemed too slow. Many troops came home thanks to a special effort called Operation Magic Carpet. By June 1947, the number of people in the military had dropped to about 1.5 million.

Contents

How Many People Served?

In 1945, as Germany and Japan were about to be defeated, the U.S. military was very large. It had 12,209,238 people serving. This was a huge increase from only 334,000 people in 1939, before the war.

Here's how the numbers broke down:

| Number of military personnel in 1945 | |

|---|---|

| Army | 5,867,958 |

| Army Air Forces | 2,400,000 |

| Navy | 3,380,817 |

| Marines | 474,680 |

| Coast Guard | 85,783 |

| Total | 12,209,238 |

Even during demobilization, about 100,000 new people were still being drafted each month. These new recruits replaced soldiers who were killed, wounded, or discharged for health reasons.

Planning for the Return Home

Even in 1943, the United States Army knew that bringing troops home would be a huge task after the war. American soldiers were spread out across 55 different war zones around the world.

Army Chief of Staff George Marshall set up special groups to figure out how to manage this big move. The War Shipping Administration (WSA) was put in charge of organizing the main effort, known as Operation Magic Carpet.

Germany Surrenders: The Point System

On May 10, 1945, just two days after Germany officially surrendered on V-E Day, the War Department announced a new system. This system would decide which Army and Army Air Force soldiers would be sent home first.

It was called the Adjusted Service Rating Score, or simply the "point system." It was designed to be fair. Soldiers earned points for:

- Each month they served in the military.

- An extra point for each month they served overseas.

- Five points for each battle medal or award they received.

- Twelve points for each child they had, up to three children.

To be eligible to go home, a soldier needed 85 points. Women in the Women's Army Corps (WACs) needed 44 points. Soldiers who reached these points would be sent home as soon as transport was ready.

The military first planned to send 2 million soldiers home in the year after the war in Europe ended. Most Navy and Marine Corps members were in the Pacific and had to wait until Japan was defeated.

Coming Home from Europe

When the war in Europe ended, 3 million American military personnel were there. The Army sorted units into four groups:

- Some units would stay in Europe as an occupation force.

- Many units would be sent to the Pacific to fight Japan.

- Other units would be reorganized and retrained.

- Units with soldiers who had enough points would go home to be discharged.

To make sure soldiers with enough points could go home, a lot of swapping happened. Soldiers eligible for discharge were moved into units that were going back to the U.S. This meant units often had many new faces, which could affect how well they worked together.

The process of sending soldiers home happened very quickly. Large camps were set up in France for 310,000 soldiers. They lived in tent cities while waiting for ships. In May 1945, 90,000 soldiers returned home. However, others had to wait months because ships were first needed for the war in the Pacific. The military tried to keep spirits high by offering education and travel programs during the waiting period.

Once in the U.S., soldiers went to military bases for their final paperwork before being officially discharged.

Japan's Defeat and Faster Returns

When Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, everyone demanded even faster demobilization. All earlier plans were quickly changed. The number of new draftees was cut, which was less than the military needed for replacements.

Now, soldiers, sailors, and marines in the Pacific could also go home. The points needed for demobilization were lowered several times. By December 1945, only 50 points were needed. To bring everyone home, ten aircraft carriers, 26 cruisers, and six battleships were turned into troop transports.

Sadly, some African-American soldiers faced unfair treatment. In December 1945, the Navy stopped 123 of them from sailing home because they said they "could not be segregated" on a troop ship.

The War Department promised that all eligible servicemen from Europe would be home by February 1946. Those from the Pacific would be home by June 1946. In December 1945 alone, one million men were discharged. Members of Congress felt "constant and terrific pressure" from soldiers and their families to speed things up even more.

Soldiers Demand Faster Demobilization

Sending so many soldiers home so quickly meant the U.S. military might not have enough people for its duties. These duties included occupying Germany, Austria, and Japan.

On January 4, 1946, the War Department changed its mind. It announced that 1.55 million eligible servicemen would be discharged over six months, not three. This news caused immediate protests from soldiers around the world.

- In Manila, 4,000 soldiers protested on Christmas 1945 when a ship meant to take them home was canceled.

- On January 6, 20,000 soldiers marched on army headquarters in Manila.

- Protests spread globally, involving thousands of soldiers in Guam, Japan, France, Germany, Austria, India, Korea, the U.S., and England. In England, 500 upset soldiers even confronted Eleanor Roosevelt.

Most commanders were understanding about the protests. General Eisenhower, the Chief of Staff, investigated the Manila protest. He found the main reason was "acute homesickness." He said no major punishment should be given to the protesters.

The military then sped up demobilization again by lowering the point requirements. However, Eisenhower banned any more protests and warned of court-martials for those who participated. The military also tried to make serving overseas more appealing. They shortened basic training for new soldiers and offered free travel for families if a soldier stayed overseas for two years.

What Happened Next?

Many military leaders felt that the fast demobilization left the U.S. military too small to do its job. Also, fewer new people were being drafted than were needed to replace those going home. The draft was stopped on March 31, 1947. For a short time, the U.S. military became an all-volunteer force.

Between mid-1945 and mid-1947, the number of people in the U.S. military dropped by almost 90 percent. It went from over 12 million to about 1.5 million.

Here's how the numbers looked in June 1947:

| Number of military personnel on June 30, 1947 | |

|---|---|

| Army (ground troops) | 684,000 |

| Army Air Force | 306,000 |

| Navy | 484,000 |

| Marines | 92,000 |

| Total | 1,566,000 |

Some experts believed this rapid demobilization made the army very weak. They thought it could hurt America's power and safety. However, others said the army in Germany still had enough strength to defend itself and manage the occupation. The occupation of Japan also went smoothly.

Because of new challenges from the Soviet Union in places like Greece and Berlin, a new (and unpopular) draft law was passed in 1948. U.S. military forces stayed at about 1.5 million people until the Korean War began in 1950.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |