Electrotyping facts for kids

Electrotyping is a cool way to make exact metal copies of things. Imagine you have a detailed model, and you want a metal version that looks exactly the same. Electrotyping uses electricity and chemicals to grow a metal layer onto a mold of that model. It was invented in 1838 in Russia by a scientist named Moritz von Jacobi.

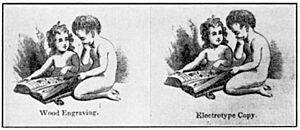

This method quickly became popular for making printing plates and even art sculptures. In the 1800s, people used electrotyping to create perfect copies of engraved metal plates, wood carvings, or even statues. Some "bronze" sculptures from the 19th century are actually copper made by electrotyping! For printing, it was a common way to make plates for letterpress printing for over a hundred years. However, by the late 1900s, newer printing methods like offset printing took over, and electrotyping became less common.

Contents

How Electrotyping Works

Electrotyping is a bit like electroplating or electroforming, but it creates a whole new metal part. Here's how it works:

Making the Mold

First, you need a mold of the object you want to copy. Since electrotyping uses wet chemicals and is done at room temperature, the mold can be made from soft materials. People used things like wax, gutta-percha (a type of natural rubber), or ozokerite (a waxy mineral).

Making it Conductive

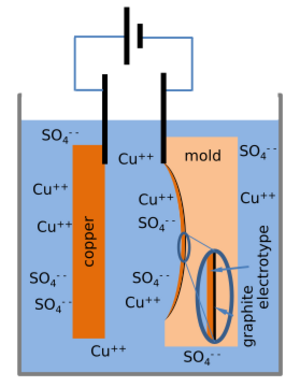

Next, the surface of the mold needs to be able to conduct electricity. This is done by coating it with a very thin layer of fine graphite powder or special paint. A wire is then attached to this conductive surface.

The Chemical Bath

The mold, with its wire, is then placed into a special liquid called an electrolyte. For making copper copies, this liquid usually contains copper sulfate and sulfuric acid. Other wires, called anodes, are also placed in the liquid. These anodes are made of the metal you want to copy, like copper.

Growing the Metal Copy

When an electric current flows, copper atoms from the anode dissolve into the liquid. At the same time, copper ions from the liquid attach to the conductive surface of the mold. This makes a layer of copper slowly grow on the mold. The longer the current flows, the thicker the copper layer becomes.

Finishing Up

Once the copper layer is thick enough, the electricity is turned off. The mold and its new metal copy (the electrotype) are taken out of the liquid. Finally, the electrotype is carefully separated from the mold.

There are two main types of electrotyping. The most common one, described above, creates a hollow metal copy that is separated from the mold. Another type deposits the metal onto the outside of a form, like a plaster shape, and the form stays inside as a core.

Who Invented Electrotyping?

Most people agree that Moritz von Jacobi invented electrotyping in 1838. He was a Prussian scientist working in St. Petersburg, Russia. When he first shared his invention, it quickly gained attention.

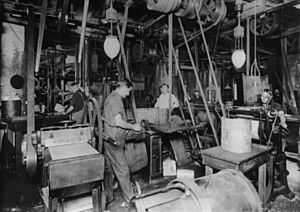

In the early days, the amount of electricity needed for electrotyping came from special batteries, like the Daniell cell or the Smee cell. These batteries were like early versions of the ones we use today. However, they couldn't provide a lot of power. By the 1870s, mechanical generators (called dynamos) became available. These generators could produce much more electricity, which made the electrotyping process much faster. What used to take hours could now be done in less than two hours!

Electrotyping in Printing

One of the first big uses for electrotyping was in printing. It was used to make copper copies of engraved metal plates or wooden carvings. These copies could then be used with movable type to create printing forms. Russia was quick to adopt this technology for government documents in 1839, with the Czar himself supporting it.

Electrotyping was also used to make entire printing plates directly from the arranged type and illustrations. This was a higher-quality option than stereotyping, which involved casting molten metal. Both methods allowed printers to save the plates for future use, especially for popular books. This meant they could reuse the original movable type. Electrotyping also made it possible to create curved plates for rotary presses, which were used for very large print runs.

The widespread use of electrotyping in printing really took off after 1872, when mechanical generators became common. Before that, printers had to use entire rooms full of chemical batteries to power the process. These batteries were slow and even gave off toxic fumes. The new generators sped up electrotyping a lot, making it much more practical.

Electrotyping was also used to make molds for individual pieces of metal type. This was easier than carving hard steel. It also helped reduce the cost of fancy typefaces that weren't used as often. However, it wasn't always as good as traditional methods, and some type foundries didn't like it because it could be used to easily copy other companies' type designs.

By the 1900s, many printing factories had special departments for electrotyping and stereotyping. These were skilled jobs with apprenticeships. However, by the late 20th century, new printing methods like offset printing became popular. Offset printing uses light-sensitive plates, so electrotyping was no longer needed.

Electrotyping in Art

Electrotyping was also used to create metal sculptures. It was an alternative to casting molten metal. These sculptures were often called "galvanoplastic bronzes," even though they were usually made of copper. Artists could also add different colors or even gold plating to these sculptures.

Electrotyping was great for making copies of valuable objects like ancient coins. Sometimes, the electrotype copies even lasted longer than the fragile originals!

Some very impressive early electrotype sculptures include twelve large gilt angels (about 6 meters or 20 feet tall) by Josef Hermann in Saint Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia, made around 1858. These sculptures needed to be light enough to be supported high up in the cathedral's dome. Other famous examples include the memorial to the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, which features five electrotype statues, and the huge gilded copper sculptures on top of the Palais Garnier (the Opera) in Paris.

In the 19th century, museums often displayed electrotype copies of ancient coins and other artifacts instead of the real ones. People also bought electrotypes for their private collections. The Victoria and Albert Museum in England, for example, collected nearly 1000 electrotyped copies of important objects from other European museums.

An interesting example of electrotyping for preservation is the copy of the poet John Keats' life-mask. The original plaster mask was made in 1816. In 1884, a copper electrotype was made, and this copy is now in better condition than the original plaster!

From the late 1800s to the 1930s, a German company called WMF made many statues and other items using electrotyping. Their statues were much cheaper than traditional bronze castings. Many memorials in German cemeteries from that time feature electrotyped statues. WMF also created larger works, like a full-sized copper electrotype of the Goethe–Schiller Monument in Weimar, Germany, which is about 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) tall.

Some sculptors also experimented with a technique where the plaster form remained inside the finished sculpture. This allowed them to create metal sculptures quickly and cheaply. However, these sculptures can sometimes degrade over time and need special care to preserve them.

Images for kids

-

A. Among the earliest and most spectacular large sculptures produced by copper electrotyping were twelve gilt angels (ca. 1858) by Josef Hermann that stand in the cupola of Saint Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia. These sculptures are 6 meters (20 feet) tall; the metal needed to be thin enough so that the weight of the sculptures could be supported high above the cathedral's floor.

-

B. Memorial (1863) to The Great Exhibition of 1851 by Joseph Durham. The uppermost statue is of Prince Consort Albert; all five statues are electrotypes. The memorial stands before Royal Albert Hall in London, England.

-

D. Electrotypes of 5th-century coins from the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard in England. Electrotype copies of coins and antiquities were produced for museum display and for private collectors.

-

Stanislaus August on a Polish Half Taler, a very rare pattern coin of 1771. Electrotype.

-

E. Reproduction of the electrotype of the poet John Keats' 1816 life-mask. The electrotype was made in 1884 by Elkington & Co. for the British National Portrait Gallery.

See also

- Luigi Galvani

- Electroforming

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |