Ellanor C. Lawrence Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ellanor C. Lawrence Park |

|

|---|---|

Walney Visitor Center

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | North of the junction of VA 28 and I-66, near Chantilly, Virginia |

| Area | 640 acres (260 ha) |

| Operated by | Fairfax County Park Authority |

| Website | Ellanor C. Lawrence Park |

Ellanor C. Lawrence Park is a cool place in Chantilly, Virginia. It's north of Centreville, right off Route 28. This park protects important history and nature in Fairfax County. Its story goes back 8,000 years!

Native Americans lived on this land first. Later, three main families owned and shaped the area: the Browns, Machens, and Lawrences. Over time, the land was a farm, a family home, and a country estate. In 1971, it became a 640-acre nature park, given to the Fairfax County Park Authority.

On the east side of Route 28, you can visit the Walney Visitor Center. Here, you'll learn about the park's past and its natural world. You can see old buildings like Walney, an 18th-century farmhouse. There are also 19th-century buildings such as a smokehouse, dairy, and ice house. You can even spot where an ice pond used to be!

You'll also find Cabell's Mill and Middlegate in the park's southeast part. Middlegate is an old stone house from the early 1800s. It's connected to Cabell’s Mill, which was built in the 1700s. Cabell's Mill is a popular spot for weddings. Middlegate is now used for park offices.

The park has about four miles of trails, mostly dirt paths. You can get to them from the Visitor Center, the pond, Cabell's Mill, or Poplar Tree Road. These trails go through different natural areas. They are great for bird watchers, runners, dog walkers, and families. You can get a trail map at the Walney Visitor Center. Bikes are not allowed on most trails. However, you can ride on the paved or gravel Big Rocky Run Stream Trail. This trail starts near Cabell's Mill and goes to the Fairfax County Parkway.

If you like fishing, you can fish in the pond and Big Rocky Run. Just make sure you follow state rules and have a fishing license.

On the west side of Route 28, the park has fun playgrounds and sports fields. You'll find fields for soccer, baseball, and softball. There's also a fitness trail with different exercise stations.

Contents

Park History: A Journey Through Time

Ellanor C. Lawrence Park has a long and interesting history. It tells the story of how people lived and used the land over many years.

The Brown Family: Early Farmers

In 1739, a man named Willoughby Newton bought a lot of land, about 2,500 acres. He didn't live there himself. Instead, he rented it out to farmers. In 1742, Thomas Brown leased 150 acres from Newton. This lease was special; it lasted for his life, his wife Elizabeth's life, and their first son Joseph's life.

Thomas Brown had to plant 200 apple trees. He also had to pay rent each year with 530 pounds of dried tobacco. Thomas Brown grew tobacco, crops, and vegetables to feed his family. As he worked hard, he earned enough money to buy more land. By 1776, Thomas and his youngest son Coleman owned about 630 acres. They might have even built the stone house that is now the Walney Visitor Center.

Tobacco farming wears out the soil. So, Thomas and Coleman started growing different crops. They grew wheat, corn, and rye instead of just tobacco. When Thomas Brown died in 1793, his son Coleman took over the farm. Coleman ran the farm until he passed away. He wanted the farm to be sold and the money shared among his daughter Mary Lewis's children. But his wife, Elizabeth, could live there for the rest of her life.

Elizabeth oversaw the farm until she died in 1840. We don't have many records from this time. She might have let her son-in-law, Coleman Lewis, manage it. Or maybe she let tenant farmers run things. By 1843, the farm was not in good shape. After Elizabeth's death, it was sold to Lewis H. Machen. He was one of Thomas Brown's great-grandchildren.

The Machen Family: A Senator's Farm

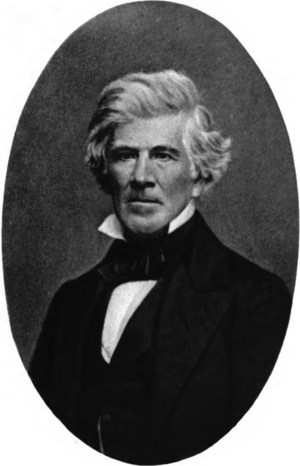

In 1843, Lewis H. Machen bought 725 acres from Coleman Brown's grandchildren. He paid $10,879 for it. Lewis moved there with his wife Caroline, daughter Emmeline, and sons Arthur and James. They lived in a wooden house near the stone house that's still there today. Lewis Machen had many valuable books. He turned the small stone house into his library and study.

Lewis Machen was not a farmer. He worked as a clerk for the United States Senate. He hoped the farm would give his family money when he retired or if he lost his job. The Machens also thought selling their Washington D.C. home would help pay for the farm. But no one wanted to buy their D.C. house. So, Lewis had to use his Senate salary to keep the farm going. He stayed in D.C. most of the time. His wife and two sons took care of the farm.

The farm was in poor condition when they bought it. But Lewis really wanted to make it better and profitable. He was interested in new farming ideas from the 1840s and 1850s. He tried rotating crops and using fertilizer like Peruvian guano. Since Lewis wasn't always at the farm, he wrote many letters to Arthur and James. He also kept detailed records in workbooks. These books show what tasks were done each day, who did them, and what the weather was like.

His oldest son, Arthur, lived at Walney as a teenager. He worked on the farm with his brother James. Arthur named the farm "Walney" because of the walnut trees in front of the house. But Arthur wasn't very interested in farming. He loved to study. He went to Harvard Law School in 1849 and became a lawyer in Baltimore, Maryland.

The Machens grew many crops for sale or to feed their animals. They grew oats, wheat, corn, radishes, and potatoes. They also raised cattle, sheep, and milk cows. They had a vegetable garden, chickens, and hogs for their own food. In the winter of 1853, they built an ice pond and an ice house. This let them collect and store their own ice. To help with the farm work, the Machens hired workers, including enslaved African Americans.

In 1859, Lewis finally retired from his Senate job. But his retirement wasn't peaceful because the American Civil War was about to begin.

The American Civil War: A Farm in the Middle of Conflict

Walney saw a lot of army movement during the American Civil War. This was because it was close to Washington D.C. In the winter of 1861-1862, over 40,000 soldiers camped near Centreville. They cut down trees for firewood, forts, and shelter. This damaged the woods, fields, and gardens. During this winter, Walney was used to house some sick soldiers. The Machen women helped care for them.

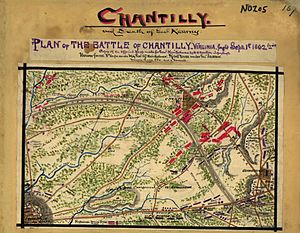

In August 1862, right after the Second Battle of Bull Run, Walney was in the path of the Union army's retreat. Union soldiers passed through Walney. They took oxen, horses, food, and supplies. They also searched the stone house. They tried to break into the wooden house where Lewis Machen was sick. Caroline Machen stopped them by standing at the door. A Union officer passing by ordered the soldiers away and stopped the attack. The next day, September 1, 1862, the Battle of Chantilly (also called the Battle of Ox Hill) happened on part of the Machen's cornfield.

Even with all the troop movements and fighting, Walney didn't lose as much property as many nearby farms. But the war was hard on the Machens. Lewis Machen died in 1863. He had left Walney to stay safe in Baltimore with Arthur. Caroline and her daughter Emmeline stayed in Baltimore for the rest of their lives. They only returned to Walney for family visits. James came back from fighting with the Confederate Army. He tried to rebuild his family's farm despite the war's damage.

After the War: New Beginnings

James Machen took over Walney after the war. He worked hard to replace the animals and farm tools lost during the fighting. In December 1874, a problem with the chimney caused the wooden house where James and his family lived to burn down. After fixing it up in 1875, James moved his family into the stone house.

James kept going and changed the farm from growing crops to a dairy farm. By 1880, he was making 3,000 pounds of butter each year! In 1881, he expanded his dairy and started making cheese too. As James got older, he began to stop farming. We don't know exactly why. It might have been because his wife Georgie died in 1895. Or maybe none of his children wanted to take over the farm. After James died in 1913, his children rented out the farm until the 1920s. During this time, the farm became very run down and was left empty until the 1930s.

The Lawrence Family: A Park is Born

In 1935, Ellanor C. Lawrence bought the property from the Machen family for $16,500. Ellanor and her husband David Lawrence had lived in Washington D.C. since 1916. Her husband was a writer and started U.S. News & World Report. The property became their country estate, a quiet escape from D.C. However, the Lawrences never lived in the Walney stone house. They rented it out to different people.

In 1942, Ellanor bought the land next to it, which included Cabell’s Mill. This added 20 acres to her property. When they stayed at their Walney estate, the Lawrences lived at Middlegate. This had been the miller's house. Both Cabell's Mill and Middlegate are still important parts of Ellanor C. Lawrence Park today.

Ellanor made some changes to the old Walney farm. She tore down some of the original farm buildings and tenant houses. She also fixed up the Walney house and Middlegate. She loved gardening and added many beautiful plants and flowers, some from Japan. Old farm fields and pastures were left to grow wild again, turning into meadows and forests.

When Ellanor C. Lawrence passed away in 1969, she left the property to her husband. She wanted it to be given to a public agency. Her goal was to protect its nature and history. In 1971, David Lawrence gave 640 acres, including Walney and Cabell’s Mill, to the Fairfax County Park Authority. He did this to honor Ellanor. In 1982, the little stone house became the Walney Visitor Center. It now teaches visitors about the park's natural and cultural history.

Natural Wonders: Plants and Animals

Ellanor C. Lawrence Park is in Virginia’s Piedmont area. It has oak-hickory and cedar forests, streams, meadows, and a pond. These different habitats help support many local plants and animals. Streams in the park, like Big Rocky Run, Walney Creek, and Round Lick Run, flow into the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

You can find many native animals in the park. There are lots of reptiles and amphibians. Scientists have found 133 different kinds of birds. More than 30 types of mammals live here too, including white-tailed deer and coyotes. Over 300 plant species have been identified. You can find a full list of the plants and animals on the park’s website.