Enset facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Enset |

|

|---|---|

|

|

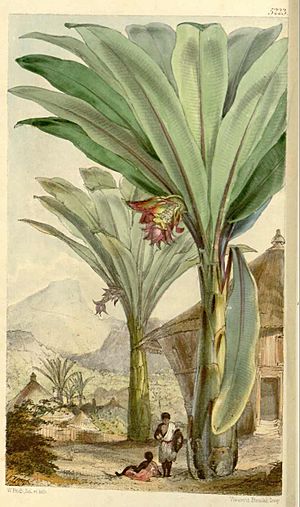

| Ensete ventricosum, by Walter Hood Fitch (1861) | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Zingiberales |

| Family: | Musaceae |

| Genus: | Ensete |

| Species: |

E. ventricosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Ensete ventricosum, often called enset or false banana, is a large plant from the banana family. It's not a true banana, but it looks very similar! This plant is grown mostly in Ethiopia, where it's a main food source for about 20 million people.

The name Ensete ventricosum was first officially used in 1947. In the wild, you can find enset growing in high-rainfall forests on mountains and along streams. It grows in many parts of Africa, from South Africa all the way up to Ethiopia, and west to the Congo.

Contents

What Enset Looks Like

Enset plants are huge, but they aren't trees. They are giant herbs that can grow up to 6 meters (about 20 feet) tall. They have a thick, fake stem made of tightly packed leaf bases. Their leaves look like banana leaves, growing up to 5 meters (about 16 feet) long and 1 meter (about 3 feet) wide. These leaves have a pretty salmon-pink line down the middle.

Enset flowers only once in its life, right from the center of the plant. These flowers hang down in huge bunches, covered by large pink leaf-like structures called bracts. The roots of the enset plant are an important food, but the fruits are not tasty and have hard, black seeds. After the plant flowers, it dies.

The Latin name ventricosum means "with a swelling on the side, like a belly." This describes the plant's shape.

Enset as a Food Source

Enset is a super important food in Ethiopia. The Food and Agriculture Organization says that enset can provide more food per area than most grain crops. Just 40 to 60 enset plants, covering a small area, can feed a family of 5 or 6 people!

This plant is Ethiopia's most important root crop. It's a traditional main food in the southern and southwestern parts of the country. It takes about four to five years for an enset plant to grow big enough to harvest. One plant can give about 40 kilograms (about 88 pounds) of food. Because it takes so long to grow, farmers plant enset at different times. This way, they always have some ready to harvest. Enset also handles dry weather better than most grain crops.

Wild enset grows from seeds. But most farmed enset plants are grown from "suckers," which are small shoots that grow from the base of a mother plant. One mother plant can produce up to 400 suckers! In 1994, about 3,000 square kilometers (about 1,158 square miles) of enset were grown in Ethiopia. Farmers often grow enset alongside other crops like sorghum or coffee.

The soft inner part of the plant's center is cooked and eaten. It's tasty and full of nutrients. In Ethiopia, over 150,000 hectares (about 370,000 acres) are used to grow enset for food. Farmers crush the trunk and flower stalk to make a starchy food. When these crushed parts are fermented, they make a food called kocho. Another food, bulla, is made from the liquid squeezed out of this mixture. Bulla can be eaten as a porridge. Kocho and bulla are full of energy. Sometimes, kocho is seen as a special food for parties and weddings. The fresh root (called a corm) can also be cooked like potatoes.

Enset is a major crop, but it faces challenges. In the past, plant diseases and dry weather have caused problems for enset farms. When there isn't enough land or water, farmers sometimes have to harvest plants before they are fully grown. This can lead to fewer enset plants being available for food. Because of this, many people who relied on enset for food security now find it harder to get enough.

Other Uses for Enset

Enset grows quickly and is sometimes grown just for its beauty in gardens. In places where it gets cold, it needs to be protected indoors during winter.

The leaves of the enset plant provide a strong fiber. This fiber is used to make ropes, string, baskets, and other woven items. Dried leaf-sheaths are used as a natural packing material, similar to how we use foam or polystyrene. Almost the entire enset plant, except for the roots, is used to feed farm animals. Fresh leaves are a common food for cattle when it's dry. Farmers also feed their animals the leftover parts from enset harvesting or processing.

Enset's History

In 1769, a Scottish traveler named James Bruce was the first to describe and draw the enset plant from Ethiopia. He knew it wasn't a true banana and said its local name was "ensete." Later, in 1853, some seeds were sent to Kew Gardens in England. People at Kew didn't realize they were enset seeds at first. But when the seeds grew into large plants, it became clear they were related to bananas.

Bruce also thought that some ancient Egyptian carvings of the goddess Isis sitting among banana-like leaves might actually be enset. This is interesting because bananas are from Southeast Asia and weren't known in ancient Egypt.

Pests and Diseases of Enset

Enset plants can get sick or be attacked by pests, which makes it harder for farmers to grow them.

Pests

The most common pest for enset is a root mealybug called Cataenococcus enset. These tiny bugs feed on the roots and the corm (the root part) of the plant. This makes the plant grow slower and easier to pull out of the ground. Enset plants can get infested at any age, but they are most at risk between their second and fourth year of growth.

Mealybugs can spread in a few ways:

- Young mealybugs can crawl short distances. Adult mealybugs usually only move if they are disturbed.

- Ants sometimes help mealybugs move around. The ants protect the mealybugs and even carry them short distances because they like to eat the sweet "honeydew" the mealybugs produce.

- Floods can carry mealybugs to new enset plants.

- The main way they spread is through dirty tools or by planting suckers that are already infected.

To stop the spread of mealybugs, farmers often pull up and burn infected plants. They might also leave the fields empty for a month, as mealybugs can only live for about three weeks without a plant to feed on.

Other pests include tiny worms called nematodes, spider mites, aphids, mole rats, porcupines, and wild pigs. Mole rats and pigs can damage the corm and the fake stem. Two types of nematodes, root lesion nematodes and root-knot nematodes, can also harm enset. They create holes and purple spots on the corm and roots, making the plant easy to uproot. Farmers can rotate their crops (plant different things in the same spot each year) to help control nematodes.

Diseases

Enset plants can also get diseases. The most well-known is a bacterial disease called bacterial wilt, caused by the bacteria Xanthomonas campestris. This disease makes the top leaves wilt and dry out, eventually causing the whole plant to dry up. The only way to stop it from spreading is to pull up, burn, and bury infected plants. Farmers also have to be very careful to clean their knives and tools used for harvesting.

Other problems include "Okka" and "Woqa." "Okka" happens when there's a lot of dry weather, and "Woqa" happens when there's too much water in the soil, which helps bacteria grow. Farmers can solve these by watering the plants during dry times or draining the soil if it's too wet.

Another disease, called black Sigatoka leaf streaks, is more common in true banana plants but can also affect enset. It causes dark brown spots with yellow edges on the leaves. This disease likes wet weather and cooler temperatures.

Enset's Importance in Ethiopian Culture

People in Ethiopia have been growing enset for a very long time, possibly for 10,000 years! It's important for many reasons, including trade, medicine, cultural identity, special ceremonies, and even how people build their homes.

Enset farming is one of the main ways people grow food in Ethiopia. It's used by about 20 million people, which is a big part of the country's population. These people mostly live in the crowded highlands of southern and southwestern Ethiopia.

The plant is very important for food security because it can handle dry periods well. Its growth might slow down, but it doesn't stop completely. Also, it can be harvested at any stage of its growth. However, as the population grows, there's more pressure on enset farms. This means less natural fertilizer is used, and there's a higher demand for enset, especially during dry times when it might be the only food available.

Gender Roles in Enset Farming

In enset farming, men and women often have different jobs. Men are usually in charge of planting new enset plants and taking care of them as they grow. Women, on the other hand, are responsible for fertilizing the plants, weeding, thinning them out, and choosing the best types of plants to grow.

Women also do the hard work of processing enset plants into food and fiber. They often work together in groups to do this, and men are usually not allowed in the field during this time. Since women are responsible for feeding their families, they decide when to harvest the plants and how much to sell.

Studies show that women know a lot about the different types of enset plants. They are often better at recognizing different varieties than men. However, sometimes women's work and knowledge are not given as much importance by researchers or even by some farmers. Women also might have less access to farming support services than men.

Men and women even have different ways of classifying enset varieties, calling them "male" or "female" based on their preferences. Men often prefer varieties that grow slowly and are resistant to diseases. Women prefer varieties that are good for cooking and can be harvested sooner. Most households tend to grow slightly more "female" varieties.

Enset Varieties and Social Groups

In Ethiopia, over 300 different types of enset have been found. This is great for keeping many different plant types (biodiversity). Farmers like to keep many varieties because each one has different good qualities. For example, one might be good for food, another for fiber, and another might resist disease. This is different from how plant breeders often try to combine many good traits into one plant.

More than 11 different ethnic groups live in the enset-growing regions, and they all have their own cultures and farming methods. This helps keep the many varieties of enset alive. Over hundreds of years, these groups have used their special farming knowledge to keep enset production going. If enset varieties disappear, some cultural practices and local words in Ethiopia might also disappear.

Enset biodiversity is also kept safe by how wealthy different households are. Richer farmers can usually afford to grow more types of enset because they have more land, workers, and animals. This means they can grow more varieties with different features. However, even poorer households try to keep as many types as possible, especially those that resist disease.

Known Varieties and Hybrids

- Ensete ventricosum 'Atropurpureum'

- Ensete ventricosum 'Green Stripe'

- Red false banana (Ensete ventricosum 'Maurelii')

- Ensete ventricosum 'Montbeliardii'

- Ensete ventricosum 'Tandarra Red'

- Ensete ventricosum 'Red Stripe'

- Ensete ventricosum 'Rubra'

Some experts believe that Ensete livingstonianum looks very similar to E. ventricosum. Both are found in the mountains of equatorial Africa.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bananero de Etiopía para niños

In Spanish: Bananero de Etiopía para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |