Estate tax in the United States facts for kids

In the United States, the estate tax is a federal tax on money or property left behind by someone who has died. This tax applies to things like money, homes, and other valuable items that are passed on through a will or state laws. It can also include things like money from a trust or certain life insurance payments.

The estate tax is part of a bigger system called the unified gift and estate tax. The other part, the gift tax, applies to money or property given away while a person is still alive.

Besides the federal government, 12 states also have their own estate taxes. Six states have "inheritance taxes," which are paid by the person who receives the money or property, not by the estate itself.

The estate tax is often debated by politicians. Some people call it the "death tax" because it's paid after someone dies. Others support it, sometimes calling it the "Paris Hilton tax" to suggest it mainly affects very wealthy people.

Many estates don't have to pay this tax. In 2021, only a small number of estates (2,584) paid federal estate tax. This is because there are many exceptions. For example, if property is left to a spouse or a recognized charity, it usually isn't taxed.

Also, there's a maximum amount of money or property an individual can give away or leave behind without paying federal gift or estate taxes. This amount changes each year. For example, in 2016, it was $5,450,000 for an individual. For married couples, this amount could be effectively doubled. Because of these high limits, only the wealthiest 0.2% of estates in the U.S. usually pay this tax. In 2018, this tax-free amount doubled to $11.18 million per person due to a new tax law. This meant about 3,200 estates no longer had to pay the federal estate tax.

The current individual tax-free amount in 2024 is $13.61 million. For a married couple, it's $27.22 million.

Contents

Federal Estate Tax Basics

The federal estate tax is charged on the total value of a person's taxable property when they die, if they were a U.S. citizen or resident.

This tax encourages very rich families to pass their money directly to future generations. This helps them avoid taxes on each transfer. Many states have removed old rules that prevented this. This means huge amounts of wealth can be put into special trusts. These trusts are designed to benefit distant family members, avoid taxes, and keep some control over the money forever.

One main reason people plan their estates is to deal with federal taxes. Only a small number of U.S. estates actually pay this tax. This is because the tax-free amounts are very high. Also, money left to a surviving spouse is completely free from estate tax. However, estates that do have to pay usually face high tax rates. People often arrange their finances to lower these taxes.

To figure out the tax, you start with the "gross estate." Then, certain deductions are taken away to get the "taxable estate."

What is the "Gross Estate"?

The "gross estate" for federal estate tax purposes often includes more property than what is usually handled by a state court after someone dies. It generally means the value of all property a person owned when they died.

It also includes other property interests that the person might not have directly owned at the time of death, such as:

- Property a surviving spouse might have a right to.

- Property given away in the three years before death, unless it was a gift that wasn't taxed or sold for its full value.

- Property given away before death where the person kept the right to use it or control it.

- Property where the new owner could only get it by outliving the person who died.

- Property given away before death that could be taken back.

- Certain types of regular payments (annuities).

- Property owned jointly with others, like bank accounts or homes, that automatically pass to the survivor. Special rules apply for property owned jointly by spouses.

- Certain rights to decide who gets property.

- Money from certain life insurance policies.

This list is not complete, but it shows that the gross estate can include many different types of assets. For example, life insurance money can be included if the person who died owned the policy or could change who received the money. Bank accounts set up to be "payable on death" are also usually included.

Deductions and the Taxable Estate

After figuring out the "gross estate," certain things can be subtracted. These are called deductions. They help lower the value of the "taxable estate."

Some common deductions include:

- Funeral costs and expenses for managing the estate.

- Money or property given to certain charities.

- Property left to the surviving spouse.

- Inheritance or estate taxes paid to states (since 2005).

The most important deduction is for property left to a surviving spouse. This can often make it so no federal estate tax is owed for a married person. However, this unlimited deduction doesn't apply if the surviving spouse is not a U.S. citizen.

How the Tax is Calculated

The tax is based on the "taxable estate" plus any taxable gifts made after 1976. For people who died after December 31, 2009, the tax rates generally start at 18% for smaller amounts and go up to 40% for very large estates.

The tax is then reduced by any gift tax that would have been paid on gifts made during life.

Credits Against the Tax

There are also credits that reduce the tax owed. The most important is a "unified credit." This credit means a certain amount of the estate is completely free from tax. This is called the "exemption equivalent" or "applicable exclusion amount."

For example, if someone died in 2008, the tax-free amount was $2,000,000. If their taxable estate plus gifts was less than or equal to that amount, they paid no federal estate tax. A tax law in 2001 planned to remove the estate tax completely for 2010. However, new laws were passed to bring it back.

A law passed in 2010 changed the tax rates for estates of people who died after December 31, 2009. It also linked the estate tax credit with the gift tax credit. For people who died in 2014, the gift tax exemption was $5,340,000.

The 2010 law also made the credit "portable." This means a surviving spouse can use any unused portion of their deceased spouse's tax-free amount. For example, if a husband used $3 million of his credit, his wife could use her own credit plus the remaining $2 million of his.

Because of these exemptions, only the largest 0.2% of estates in the U.S. have to pay any estate tax.

Filing and Paying the Tax

If an estate is larger than the current federal tax-free amount, the person in charge of the estate (the executor) must pay any estate tax due. They also need to file a special form (Form 706) with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This form must also be filed if a surviving spouse wants to claim their deceased spouse's unused tax exemption.

The form needs detailed information about the value of the estate's assets and the deductions claimed. This ensures the correct tax amount is paid. The deadline for filing this form is 9 months after the person's death. The payment deadline can sometimes be extended, but the form must still be filed on time.

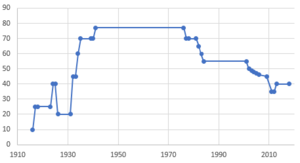

Exemption Amounts and Tax Rates Over Time

| Year | Exclusion amount |

Max/top tax rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | $175,000 | 70% |

| 1982 | $225,000 | 65% |

| 1983 | $275,000 | 60% |

| 1984 | $325,000 | 55% |

| 1985 | $400,000 | 55% |

| 1986 | $500,000 | 55% |

| 1987 | $600,000 | 55% |

| 1998 | $625,000 | 55% |

| 1999 | $650,000 | 55% |

| 2000 | $675,000 | 55% |

| 2001 | $675,000 | 55% |

| 2002 | $1 million | 50% |

| 2003 | $1 million | 49% |

| 2004 | $1.5 million | 48% |

| 2005 | $1.5 million | 47% |

| 2006 | $2 million | 46% |

| 2007 | $2 million | 45% |

| 2008 | $2 million | 45% |

| 2009 | $3.5 million | 45% |

| 2010 | Repealed | |

| 2011 | $5 million | 35% |

| 2012 | $5.12 million | 35% |

| 2013 | $5.25 million | 40% |

| 2014 | $5.34 million | 40% |

| 2015 | $5.43 million | 40% |

| 2016 | $5.45 million | 40% |

| 2017 | $5.49 million | 40% |

| 2018 | $11.18 million | 40% |

| 2019 | $11.4 million | 40% |

| 2020 | $11.58 million | 40% |

| 2021 | $11.7 million | 40% |

| 2022 | $12.06 million | 40% |

| 2023 | $12.92 million | 40% |

| 2024 | $13.61 million | 40% |

The table shows how much of an estate was tax-free each year. Estates worth more than these amounts would owe tax only on the amount above the exemption.

For example, if an estate was worth $3.5 million in 2006, the tax-free amount was $2 million. So, only $1.5 million was taxable. The tax rate in 2006 was 46%, meaning the tax paid would be $690,000.

A tax law in 2001 had planned to remove the estate tax for one year (2010). It would then return in 2011 with a lower tax-free amount. However, in December 2010, Congress passed a new law. This law set the tax-free amount at $5 million per person and the top tax rate at 35% for 2011 and 2012.

Then, in January 2013, another law was passed. This law made the $5 million tax-free amount (adjusted for inflation) permanent for U.S. citizens and residents. It also set the maximum tax rate at 40% for 2013 and beyond. The tax-free amounts set by a 2017 tax law, which were $11,180,000 for 2018 and $11,400,000 for 2019, are set to change again at the end of 2025.

Rules for Non-Residents

The large tax-free amounts mentioned above apply only to U.S. citizens or residents. People who are not U.S. citizens or residents (called non-resident aliens) have a much smaller tax-free amount, usually $60,000. This amount might be higher if there's a special tax agreement (treaty) with their home country.

For estate tax purposes, being a "resident" means someone who lived in the U.S. or District of Columbia with no plans to move. This is different from how "resident" is defined for income tax.

A non-resident alien only pays estate tax on the property they own that is located in the United States. These rules can also be changed by tax treaties. The U.S. has estate tax treaties with many European countries, Canada, Australia, and Japan.

Noncitizen Spouse Rules

The estate tax rules are different if a surviving spouse is not a U.S. citizen.

If property is owned jointly with a noncitizen spouse, it's usually all considered part of the deceased person's estate. This is unless the estate can prove how much the noncitizen spouse contributed to buying the property.

U.S. citizens with a noncitizen spouse don't get the same unlimited tax deductions for property left to their spouse as those with a U.S. citizen spouse. Also, the estate tax exemption cannot be "portable" between spouses if one of them is not a citizen.

State Estate and Inheritance Taxes

Currently, 15 states and the District of Columbia have an estate tax. Six states have an inheritance tax. Maryland has both.

In states with an inheritance tax, the tax rate depends on who receives the property. For example, in Kentucky, the tax depends on the relationship between the person who died and the person receiving the property. Inheritance taxes are paid by the people who inherit, not by the estate itself.

For people who died in 2014, 12 states and the District of Columbia had only estate taxes. The tax-free amounts in these states varied greatly. Some states had amounts similar to the federal level (around $5.34 million), while others had much lower amounts (like $675,000 in New Jersey). The most common tax-free amount was $1 million. Top tax rates in these states ranged from 12% to 19%.

Five states (Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) had only inheritance taxes. The tax-free amounts here also varied a lot. Some states had no tax-free amount for property left to unrelated people. Others had unlimited tax-free amounts for close family members like children or parents. No states taxed property left to surviving spouses. Top tax rates ranged from 4.5% to 18%.

Maryland is the only state that has both an estate tax and an inheritance tax. However, the estate tax paid reduces the inheritance tax, so you don't pay both taxes fully.

Reducing Estate Taxes

Very wealthy people often use strategies to reduce the amount of estate tax their families will pay. These can include:

- Giving away money or property while they are alive. These "lifetime transfers" might have lower tax rates than transfers at death.

- Transferring property through special insurance trusts or other types of trusts.

- Giving gifts to charity.

- Making the most of each spouse's tax-free transfer opportunities.

- Simply spending more of their money during their lifetime.

A 2021 study found that many of the richest Americans use special trusts to avoid paying estate taxes when they die.

History of the Estate Tax

Taxes on estates or inheritances have existed in the United States since the 1700s. A temporary tax in 1797 applied different rates based on the size of the inheritance. This tax was removed in 1802. Similar taxes were used in the 1800s to help fund wars, but they were also removed when no longer needed. The modern estate tax began in 1916.

A tax law in 2001 gradually lowered the estate tax rates until it was completely removed for the year 2010. However, this change was not permanent. The tax was scheduled to return to a 55% rate in 2011.

In late 2010, Congress passed a new law. This law set the tax at 35% for 2011 and 2012 on estates worth more than $5 million. Like the 2001 law, this one also had an end date. It would have returned the tax to 55% in 2013. But on January 1, 2013, Congress made the 40% tax on estates over $5 million permanent.

Estate Tax and Charity

One important question about the estate tax is how it affects giving to charity. The estate tax encourages charitable giving after death because it allows a tax deduction for gifts to charity. It can also encourage giving during life. However, it could also reduce charitable gifts overall.

Studies suggest that removing the estate tax could reduce charitable gifts by billions of dollars each year. This would mean non-profit organizations would lose a lot of money.

The estate tax directly lowers the cost of giving to charity after death. This is because the amount given to charity is not taxed. So, if the estate tax is removed, the "price" of giving to charity goes up. This is one reason why removing the tax might lead to less charitable giving.

Debate About the Estate Tax

The estate tax is a topic that often causes strong political arguments. Generally, the debate is between those who oppose any tax on inheritance and those who think it's a good policy.

Arguments for the Estate Tax

People who support the estate tax say that taxing large inheritances (currently over $12 million) is a fair way to fund the government. They argue that removing the estate tax would only help the very wealthy. This would leave a bigger tax burden on working people. Supporters also believe that efforts to remove the tax often rely on people not fully understanding it.

Experts like William Gale and Joel Slemrod give three reasons for taxing at death:

- It helps show how much wealth a person had during their life.

- Taxes at death might encourage people to work and save more during their lives than other types of taxes.

- It's a good time to assess all the wealth transfers a person made.

Supporters also point out that the estate tax only affects very large estates. It has many credits that allow a big part of even large estates to avoid tax. They note that getting rid of the estate tax would mean tens of billions of dollars less for the federal budget each year. They argue it helps prevent wealth from staying in wealthy families forever and supports a system where richer people pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes.

A main reason for supporting the estate tax is the idea of equal opportunity. This view highlights how wealth and power are connected in society. Arguments that justify wealth differences based on talent or hard work don't support differences that come from simply inheriting money. This view is strengthened by the idea that those who are very privileged should pay more for society's costs.

Winston Churchill once said that estate taxes are a "certain corrective against the development of a race of idle rich." Some research suggests that the more wealth older people inherit, the more likely they are to stop working. A 2004 report found that removing the estate tax would reduce charitable giving by 6–12%. Experts also say that removing the tax would increase government debt.

Economist Robert Reich said that if the estate tax continues to be reduced, the children of the wealthiest people will own more and more of the country's assets. He called this "unfair; it's unjust; it's absurd."

Supporters of the estate tax also disagree with calling it a "double tax." They point out that much of the money subject to estate tax was never taxed before. This is because it came from "unrealized" gains, like the increase in value of a stock that hasn't been sold yet.

They also argue there's a long history of limiting inheritance. In ancient times, wealthy people often spent a lot of their money on funeral ceremonies. This helped prevent huge differences in wealth, which supporters say helped prevent social problems.

Economist Jared Bernstein said, "People call it the 'Paris Hilton tax' for a reason. We live in an economy now where 40 percent of the nation's wealth accumulates to the top 1 percent. And when these folks leave bequests to their heirs, we're talking about bequests in the tens of millions."

Supporters of free markets, like Adam Smith and the founding fathers, believed people should get rich through hard work and competition. They were against inherited wealth, which was common in the aristocratic systems they fought against. Smith wrote that allowing estates to be passed down forever is "absurd."

Inherited wealth can discourage hard work in those who receive it. If estate tax income is reduced, working people might have to pay more taxes. If estate tax was increased, it could allow for lower taxes on working people. This would encourage more work and risk-taking. But reducing taxes on inherited wealth might make people work less.

If many of the wealthiest people get their money through inheritance, it can seem unfair to those who work hard but struggle. This can create a feeling that the system is rigged. It can also lead to political instability. Reducing the estate tax makes this situation worse. Increasing it can promote a fairer market, especially if the extra tax money is used to encourage productivity.

Oscar Mayer heir Chuck Collins argues that concentrating wealth in a few hands harms both the economy and democracy. He quotes Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis: "You can have concentrated wealth in the hands of a few or democracy. But you can't have both."

Arguments Against the Estate Tax

Some people oppose the estate tax based on ideas of individualism and a market economy. They believe people shouldn't be "punished" for working hard and wanting to pass on their wealth. They argue that families shouldn't have to deal with both a death and a tax bill on the same day.

Another argument is that governments might not use tax money for the public good. Some argue that inherited wealth allows people, especially young people, to pursue important careers that don't pay much. They also say that in the U.S., museums and cultural places get most of their money from wealthy foundations. This means American culture is shaped more by citizens' choices than by government officials.

Other arguments against the estate tax focus on its economic effects. Some research suggests it discourages people from starting businesses. A 1994 study found that a 55% tax rate was like doubling an entrepreneur's income tax rate. The estate tax also creates a lot of paperwork and costs for people to follow the rules. Some studies estimated these costs were almost as much as the tax money collected.

Another argument is that the tax can make it harder to make important decisions about assets. For example, upcoming estate taxes might discourage investing in a business. It might even force people to sell off parts of a business or farm. This is especially true when an estate's value is close to the tax-free amount. Older people might choose to reduce risks and protect their money by selling assets or using tax avoidance methods.

Farmers often argue that the estate tax is a burden. Farming needs a lot of expensive assets like land and equipment to make money. The tax might force surviving family members to sell land or equipment to keep the farm running. Farmer groups have asked for higher tax-free amounts for farms.

Another argument against the estate tax is about how it's enforced. Some say that because the tax can be avoided with careful planning, it mostly punishes those who don't plan ahead or use unskilled advisors. Also, differences in tax rates might encourage wealthy people to move their money outside the U.S. This could mean less tax money is collected than expected. However, most countries have similar or higher inheritance taxes.

The Term "Death Tax"

The term "death tax" has been used in U.S. tax laws since 1954 to refer to estate, inheritance, and other taxes related to someone's death.

The modern U.S. estate tax was created in 1916. Opponents of the estate tax started calling it the "death tax" in the 1940s. This term highlights that death is the event that causes the tax to be owed on a person's former assets.

The use of "death tax" became more common in the 1990s. This happened after a proposal to lower the tax-free amount was very unpopular. Surveys suggest that poor people oppose inheritance and estate taxes even more strongly than rich people.

The term "death tax" emphasizes that death triggers a tax on the deceased person's assets. An estate tax is paid from the deceased person's assets before they are given out. An inheritance tax is paid by the person who receives the money or property.

Supporters of the tax say "death tax" is not precise. They argue it has been used since the 1800s to mean all taxes related to transfers at death.

Experts like Chye-Ching Huang and Nathaniel Frentz say the idea that the estate tax is best called a "death tax" is a myth. They point out that only a very small percentage (0.14%) of estates actually owe the tax.

A Republican pollster named Frank Luntz wrote that the term "death tax" "kindled voter resentment in a way that 'inheritance tax' and 'estate tax' do not."

Related Taxes

The federal government also has a gift tax. This tax works similarly to the estate tax. Its purpose is to stop people from avoiding estate tax by giving away all their money before they die.

There are two main ways to avoid the gift tax:

- You can give up to $15,000 per person per year without paying tax (as of 2020). A married couple can give up to $30,000 per person per year.

- There's also a lifetime tax-free amount for total gifts. This amount is linked to the estate tax exemption.

Many estate plans involve giving away the maximum tax-free amount to many people. This reduces the size of the estate. It also lets the person giving the gift see others enjoy the money.

Also, very large transfers (over $5 million, adjusted for inflation) might be subject to a generation-skipping transfer tax. This applies if the money is given to someone two or more generations younger than the giver (like a grandchild).

The total tax burden from estate, inheritance, and gift taxes can affect the number of businesses in the U.S. An increase in gift tax can slow the growth of new companies, especially small ones. This is because small business owners might struggle to get enough money to pay the estate tax without selling off their businesses.

Loopholes

Many very wealthy people avoid the estate tax by moving money into trusts or charitable foundations before they die.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |