Esther Roper facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Esther Roper

|

|

|---|---|

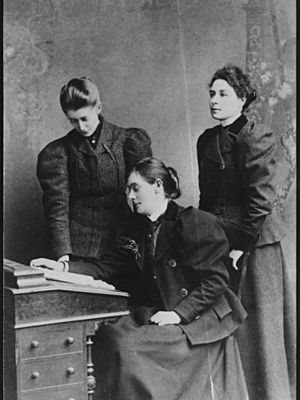

Roper as a student at Owens College, c. 1892

|

|

| Born | 4 August 1868 |

| Died | 28 April 1938 (aged 69) Hampstead, London, England

|

| Resting place | St John-at-Hampstead |

| Occupation | Organiser, suffragist |

| Partner(s) | Eva Gore-Booth |

Esther Roper (born August 4, 1868 – died April 28, 1938) was an important activist from Ireland and England. She worked hard for fairness, fighting for equal job opportunities and voting rights for women. She especially helped women who worked in factories and other jobs.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Esther Roper was born near Chorley, England, on August 4, 1868. Her father, Edward Roper, worked in a factory and later became a missionary. Her mother, Annie Roper, was the daughter of Irish immigrants. Esther was educated by the Church Missionary Society.

She was one of the first women to study for a degree at Owens College in Manchester. In 1886, she was allowed to join as part of a test. This test was to see if women could study at college without harming their health. In 1897, Esther and another student, Marion Ledward, started a newsletter called Iris. This newsletter was for female students. It came out twice a year until 1894. It talked about issues affecting women's education and helped students connect with each other.

In 1891, Esther graduated from Owens College with top honors. She studied Latin, English Literature, and Political Economy. She stayed involved with the college and became a leader in its women-only Social Debating Society. In 1895, she helped create the Manchester University Settlement in Ancoats. This place offered education and cultural activities to poor working people. She was chosen for its main committee in 1896.

Fighting for Women's Right to Vote

From 1893 to 1905, Esther worked as the paid secretary for the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage. People say Esther brought new energy to this group. Before her, the group had lost its way after the previous secretary, Lydia Becker, passed away.

Esther made the campaign for women's votes bigger. She changed the focus from just helping middle-class women. She actively worked to get working-class women involved. They signed petitions and spoke at events. In 1897, the group changed its name to the North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage (NESWS). It also became part of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

Meeting Eva Gore-Booth

In 1896, Esther was very tired and went on holiday to Italy. There, she met Eva Gore-Booth, an Irish poet and aristocrat. They became very close friends. The next year, Eva left her privileged life to live with Esther in Manchester. Esther later wrote about their meeting in Italy. She said, "For months illness kept us in the south. We spent the days walking and talking on the hillside by the sea. Each was interested in the work and thoughts of the other. We soon became friends and companions for life."

Working for Justice with Eva Gore-Booth

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Esther and Eva helped organize groups of working women. These included flower-sellers, circus performers, barmaids, and coal miners. Their right to work was being threatened by new laws and social campaigns. Esther and Eva set up public meetings, protests, and visits to Parliament.

They argued that women's jobs were at risk. They said women could make their own choices about their work. They also pointed out that working women had no vote, which made them powerless in the workplace. In 1900, they started a quarterly newspaper called the Women's Labour News. It aimed to bring women workers together and ran until 1904.

In 1903, the two friends helped create a committee for women textile and other workers. This group organized the campaign for the first woman to run in a general election. In 1905, Esther became secretary of another group for working women's voting rights.

After 1906, Esther and Eva moved away from the Women's Social and Political Union. They did not agree with their militant tactics. They also felt that Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader, was not interested in helping working-class women.

In 1913, Esther and Eva moved to London because of Eva's health. In 1916, they started a private journal called Urania. It shared their new ideas about gender. It was published six times a year. It included articles from newspapers and original writings.

They were strong supporters of peace during the First World War. They worked with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. They helped support the wives and children of men who refused to fight in the war. After the war, they worked to end the death penalty and improve prisons.

Later Years and Death

After Eva Gore-Booth passed away in 1926, Esther worked to keep her friend's memory alive. She edited and wrote introductions for Eva's poems and letters. Esther asked artist Ethel Rhind to create a stained glass window to remember Eva. It was put in a building in Ancoats in June 1928. Sadly, the building was torn down in 1986, and the window was lost.

In her later years, Esther continued to fight for social justice. She signed many letters to The Times newspaper. These letters were about equal treatment for men and women in jobs. Esther died of heart failure in April 1938. She was buried next to Eva Gore-Booth in Hampstead. A special quote was carved on their gravestone. Eva's sister, Constance Markievicz, wrote about Esther: "The more one knows her, the more one loves her. I am so glad Eva and she were together. I am so thankful that her love was with Eva to the end."

Remembering Esther Roper

Esther Roper's name and picture are on the base of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London. This statue was revealed in 2018. It honors women who fought for the right to vote.

See also

In Spanish: Esther Roper para niños

In Spanish: Esther Roper para niños