Fort Mose facts for kids

|

Fort Mose Historic State Park

|

|

Site of the old fort

|

|

| Location | St. Augustine, Florida |

|---|---|

| Area | 24 acres (9.7 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 94001645 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 12, 1994 |

| Designated NHL | October 12, 1994 |

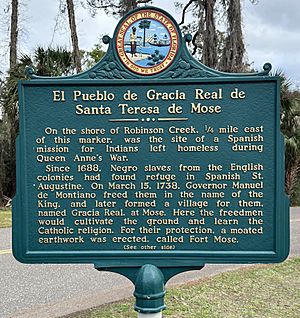

Fort Mose (originally called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose) was a Spanish fort near St. Augustine, Florida. In 1738, the Spanish governor, Manuel de Montiano, created this fort as a safe place for free Black people. It was the first legally recognized free Black settlement in what would become the United States.

The first fort was briefly left empty after a battle in 1740. But it was rebuilt nearby and used again by free Africans from 1752 to 1763. Fort Mose was named a National Historic Landmark on October 12, 1994.

Today, Fort Mose is a Florida State Park. It has a visitors' center, a small museum, and a new replica of the 1738 fort. This replica was finished and opened to the public in May 2025. The park is on the edge of a salt marsh, close to the water.

While the exact spot of the first fort is still a mystery, archaeologists found the second fort's location in 1986. The park protects this important historical site. Fort Mose is also a key stop on the Florida Black Heritage Trail. It sometimes hosts outdoor concerts, like a blues concert held in February 2023.

Contents

A Place for Freedom: Fort Mose History

Spanish Florida Offers Freedom

Long ago, in 1689, Spanish Florida started offering safety to enslaved people. These people were escaping from British colonies like Virginia. Many sought refuge in St. Augustine, Florida, where Spanish settlers and Afro-Spanish people had lived since the late 1500s.

In 1693, King Charles II of Spain made an important rule. He said that any enslaved person who escaped to Florida would be free. To gain this freedom, they had to become Catholic and serve in the Spanish army for four years. By 1742, this community of free Black people, sometimes called "maroons," had grown. The Spanish used them as a first line of defense against attacks on Florida.

Building Fort Mose

In 1738, Governor Montiano ordered the building of Fort Mose. It was about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of St. Augustine. Any enslaved person who escaped and reached the Spanish was sent there. If they accepted Catholicism and served in the army, they became free.

The leader of the fort's Black militia was Francisco Menéndez. He was born in Africa, captured, and brought to the Carolina colony as an enslaved person. Like many others, he escaped to Spanish Florida. Menéndez became a respected leader after bravely helping defend St. Augustine in 1728. He was the main leader of the free Black community at Mose.

Fort Mose was the first place in what would become the United States where free Black people could legally settle. About 100 people lived there. The village had a wall, homes, a church, and an earthen fort.

Life at Fort Mose

Fort Mose was located on a small tidal channel called Mose Creek. This gave the settlers easy access to the rich natural resources of the area. They could find oysters, fish, and other wild foods in the salt marshes and tidal creeks. Studies of animal bones found at the site show that the people of Mose ate a lot of seafood and wild foods, similar to nearby Native American communities.

News of Fort Mose spread to the British colonies of South Carolina and Georgia. It encouraged more enslaved people to escape. Other Black people and their Native American allies helped runaways travel south to Florida. The Spanish colony needed skilled workers, and these freedmen also made St. Augustine's military stronger.

The existence of Fort Mose may have helped inspire the Stono Rebellion in 1739. This revolt involved enslaved Africans, many from the Kingdom of Kongo, who tried to reach Spanish Florida. Some succeeded and quickly adapted to life there, as they spoke Portuguese and were already Catholic.

Defending Spanish Florida

As a military outpost, Fort Mose protected the northern entrance to St. Augustine. Most of its residents came from different parts of West Africa, like the Kongo and Mandinka regions. They had been forced into slavery in the Carolinas. On their journey to freedom in Florida, they often met and interacted with Native American groups.

The people of Fort Mose formed alliances with the Spanish and their Native American friends. They fought against their former British masters. After some residents were killed by Native American allies of the British, Governor Montiano ordered the fort to be abandoned. Its people moved to St. Augustine. The British then took over the empty fort.

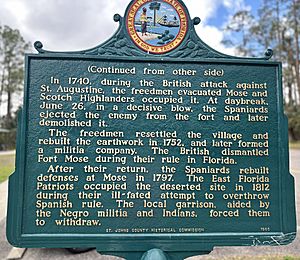

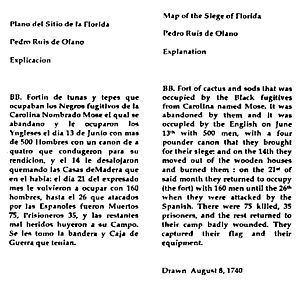

The Black militia fought alongside Spanish soldiers against British forces in 1740. This was during a conflict called the War of Jenkins' Ear. A combined force of Spanish troops, Native American allies, and the free Black militia attacked the British. They defeated them and destroyed the fort. The British were forced to retreat to Georgia. The Black Spanish militia also helped in a Spanish counterattack in 1742.

By 1752, the Spanish had returned and rebuilt Fort Mose in a slightly different spot. The new governor moved most of the free Black people back into this defensive settlement.

Leaving Fort Mose

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris gave East Florida to the British. Most of the free Black residents, along with the Spanish settlers, moved to Cuba. At that time, about 3,000 Black people lived in St. Augustine and Fort Mose. About three-quarters of them were formerly enslaved people.

The British repaired the fort after the Spanish left. The Spanish returned in 1784 and used the fort again as a military outpost. Later, American groups tried to capture Florida for the United States. An attack by Spanish and Native American allies (including Black fighters) destroyed the fort for the last time in 1812.

Fort Mose's Lasting Impact

Fort Mose was a safe haven for enslaved people, mainly from South Carolina and Georgia. It is considered a very important site on the Florida Black Heritage Trail. The National Park Service sees it as an early example of the Underground Railroad. This was a network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom before the American Civil War.

Finding and Studying the Site

In 1968, a local historian and amateur archaeologist named Frederick Eugene "Jack" Williams found the general location of the fort using an old map. He bought the land and started a campaign to have the site excavated.

From 1986 to 1988, a team of experts, including Kathleen Deagan and Jane Landers, studied Fort Mose. Their work helped pinpoint the location of the second fort, built in 1752. Their discoveries showed how important Africans were in the conflicts between European powers in the southeastern United States.

Historian Jane Landers found documents in old archives that tell us about the people of Mose. In 1759, the village had 22 palm-thatched huts. These housed 37 men, 15 women, 7 boys, and 8 girls. The people grew their own food. The men guarded the fort or patrolled the area for the Spanish. They attended Mass in a wooden chapel. Most married other refugees, but some married Native American women or enslaved people from St. Augustine.

In the first year of digging, archaeologists found parts of the fort's structures. These included its moat, earthen walls, and wooden buildings. They also found many artifacts: military items like gunflints and metal buckles, household items like pipes and ceramics, and food remains like burnt seeds and bones.

From 2019 to 2024, new archaeological digs took place at the site. These excavations were unique because they happened both on land and underwater in the surrounding creeks. They uncovered many domestic and military items, as well as food remains from the Black militia who lived there from 1752-1763.

State Park and Replica Fort

Fort Mose Historic State Park was created after the first excavations. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994. It was later recognized as a World Heritage Site.

Today, you can see artifacts in the museum at the park's Visitor Center. Outside, signs explain the site's history. The park also has three replicas of historical items: a cooking hut (choza), a small garden, and a Spanish flat boat (barca chata).

In January 2024, work began on a full-scale replica of the 1738 fort. This project had been a goal of the Fort Mose Historical Society since the 1990s. Major donations and grants helped secure the funding needed. The replica was completed and opened to visitors on May 9, 2025.

Fort Mose in Books

The story of Fort Mose is told in a book for young people published in 2010 by Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon. It includes facts, sources, and illustrations. Jane Landers has also written a detailed history of Spanish Florida that covers Fort Mose.

Gallery

These panels are posted at the Visitor Center in Fort Mose Historic State Park.

See also

In Spanish: Fuerte Mosé para niños

In Spanish: Fuerte Mosé para niños

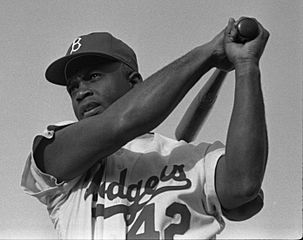

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |