Geneviève Thiroux d'Arconville facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte Thiroux d'Arconville

|

|

|---|---|

Painting of scientist and historian Mme d'Arconville, 1750

|

|

| Born | 17 October 1720 |

| Died | 23 December 1805 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Chemical study of putrefaction |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Influences | Pierre-Joseph Macquer, Antoine de Jussieu |

| Influenced | Antoine-François Fourcroy |

Marie Geneviève Charlotte Thiroux d'Arconville (born Darlus, also known as la présidente Thiroux d’Arconville) was a French writer, translator, and chemist. She lived from October 17, 1720, to December 23, 1805. She is best known for her detailed studies on how things rot, called putrefaction. She shared her findings in her book Essay on the History of Putrefaction in 1766.

Contents

Marie d'Arconville's Early Life

Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte Darlus was born in Paris on October 17, 1720. Her parents were Françoise Gaudicher and Guillaume Darlus. Her father was a "tax farmer," meaning he collected taxes for the government. He would keep some of the money for himself.

Marie's mother died when she was only four years old. Many governesses helped raise and teach her. As a young child, she loved sculpture and art. But when she learned to write at age eight, writing books became her main passion. She later told friends that she always needed a pen in her hand to think.

Marriage and Early Adult Life

At just 14 years old, Marie asked to marry Louis Lazare Thiroux d'Arconville. He was also a tax farmer. Later, he became a judge in the Parliament of Paris, a high court. It was unusual for women at that time to ask for marriage. They married on February 28, 1735, and had three sons.

As a married woman, Marie enjoyed theater and opera. This was common for wealthy women. She reportedly watched a play called Mérope fifteen times. However, at age 22, she got smallpox, a serious disease. It left her face badly scarred. After this, she stopped going out much. She spent her time studying and focusing on religion instead.

Thiroux d'Arconville studied English and Italian at home. She also took science classes at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. This was a famous center for medical education. It offered courses in physics, anatomy, botany, and chemistry. Marie likely took anatomy and chemistry classes.

She also invited famous scientists to her home. Like many wealthy women, she collected rare plants and stones. But she wanted to learn more. So, she set up her own chemistry lab at home. She filled it with equipment and ordered many books from the national library of France.

At first, she worked as a botanist, sending plant samples to the Jardin des Plantes. Later, she focused on chemistry. She studied with Pierre Macquer, a chemistry professor at the Garden. Women had a strong presence in French literature. But because of her scars, Marie chose to focus on her lab work. She did not join the social gatherings called salons.

Becoming a Translator

Marie loved learning and British culture. This led her to translate many English books into French. Translating was a common way for women to be involved in learning. Thiroux d'Arconville often added her own thoughts to the books she translated. But she never put her name on them.

As a woman scholar, she faced challenges. She once wrote that if women's books were bad, they were laughed at. If their books were good, people said a man must have written them. She said women were left with only "ridicule for letting themselves be called authors."

First Translations

People said Thiroux d'Arconville had trouble sleeping. She worked on many projects at once to stay busy. Her first published work was Advice from a Father to his Daughter in 1756. This was a translation of a book about good behavior. In her introduction, she wrote about how governesses often raised daughters. She felt mothers did not want to teach them.

In 1759, she translated Chemical Lectures by Peter Shaw. Professor Macquer encouraged her to do this. Thiroux d'Arconville fixed errors in Shaw's work. She also added a history of practical chemistry to the beginning. She started with alchemy, which she said was not a true science. She believed real chemistry began with scientists like Johann Joachim Becher and Herman Boerhaave.

She used the Bible to discuss the history of chemistry in her introduction. This was common then, as science was seen as a way to understand God's creations better.

Working with Jean-Joseph Sue

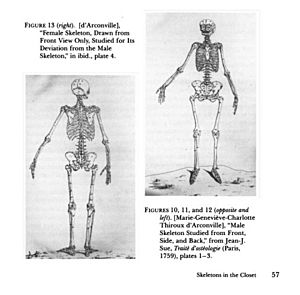

Also in 1759, Thiroux d'Arconville translated Treatise on Osteology by Alexander Monro. To write her introduction, she asked for help from Jean-Joseph Sue. He was an anatomy professor and a book reviewer. In her introduction, she admitted she had limits in her knowledge. She suggested other books for more information.

She also reorganized Monro's text and added pictures. Monro thought pictures were not accurate or needed. But Thiroux d'Arconville believed they could help with learning.

It is believed that Jean-Joseph Sue directed the creation of the images. Thiroux d'Arconville likely gave ideas and paid for them. The skeletons in the book seemed to be modeled after her. They had wide hips and narrow lower legs, possibly from the corsets she wore. However, one part of the drawing was wrong. The female skull was shown smaller than the male skull compared to the body. It should have been the other way around. Since she remained anonymous, people thought Sue was the only author.

More Translations

Thiroux d'Arconville's next books were Moral Thoughts and Reflections on Diverse Subjects in 1760. Then came On Friendship in 1761, and On Passions in 1764. These works showed her interest in good behavior. They stressed the importance of being good and pure. This was a very important idea in the 1700s, especially for women.

In On Passions and On Friendships, she wrote that friendship helps people think clearly. But too much strong emotion, especially love and ambition, could be dangerous. These books were also published without her name.

Studying How Things Rot (Putrefaction)

While working on her translations, Thiroux d'Arconville also began studying putrefaction. This is the process of how plants and animals decay or rot. She first looked at the research of John Pringle. He was a military doctor who studied what made wounds become infected.

Thiroux d'Arconville believed that to understand rotting, you needed to know how matter changes. For ten years, she recorded her experiments. She rotted food under different conditions to see if she could slow it down. She found that keeping matter away from air and exposing it to copper, camphor, or cinchona could delay rotting.

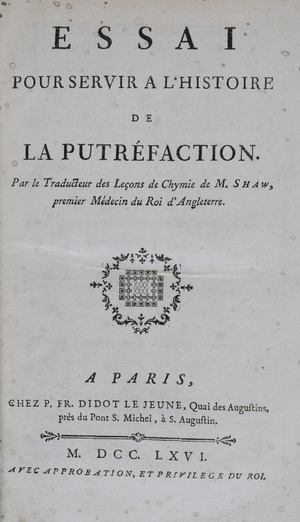

She published Essai pour servir a l'histoire de la putref́action (Essay on the History of Putrefaction) in 1766. The book described over 300 careful experiments. She remained anonymous again. One reviewer wrote that the author "must be a highly distinguished physician with a deep knowledge of both chemistry and medicine."

In her essay, she honored Pringle but also pointed out differences in their findings. She disagreed with him about chamomile's ability to delay rotting. Thiroux d'Arconville said her work improved Pringle's ideas. She also explained why she studied putrefaction. She felt it was an unexplored field that could benefit society. This idea fit well with the thinking of the 1700s. People believed that gaining knowledge to help society was very important. Women were expected to learn and pass that knowledge to the next generation.

Later Years and Challenges

The year after her putrefaction study, Thiroux d'Arconville and her family moved. They went to an apartment in the Marais District of Paris. For a while, she stopped writing because her husband's older brother died. She continued to be friends with and talk to male scholars.

Between 1767 and 1783, she started writing more novels and historical biographies. One novel was Memoirs of Mademoiselle Valcourt in 1767. This story is about two sisters. One loves society, and the other gets smallpox and gives up on love. Many think the sisters represent different parts of Thiroux d'Arconville's own life.

She also wrote many history books using the King's Library. These included Life of the Cardinal d’Ossat (1771) and Life of Marie de Medeci (1774). Critics said her biographies lacked style. This was common for female authors then, as they were often seen as less skilled than men. However, in her introduction to Life of the Cardinal d’Ossat, she wrote that details were important to understand a person's life.

Thiroux d'Arconville stopped publishing after 1783. But she wrote memoirs that were never printed. These included a twelve-volume collection of various writings. They were lost for a long time but found again in the late 1900s. In one memoir from 1801, she tried to make sense of her life. She did this through a collection of "thoughts, reflections, and anecdotes."

Thiroux d'Arconville did not like the ideas of the Enlightenment thinkers. She was very scared when the French Revolution began. In 1789, her husband died. She was then put under house arrest and later imprisoned with her family. Her oldest son, Thiroux de Crosne, who was a police chief, went to England in 1789. He returned in 1793 and was arrested and killed the next year.

Six months after her son died, Thiroux d'Arconville was allowed to go home. She lived there with her sister, sister-in-law, and grandson. By this time, she had lost her money. Her younger sons needed financial help. Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte Thiroux d'Arconville died at her home in Marais on December 23, 1805.

Her Lasting Impact

Thiroux d'Arconville's life was typical for many women of her time. She followed the rules for how a mother and wife should act. She also embraced religion. She avoided public arguments, which is why she stayed anonymous.

She was not considered a feminist. She thought women wasted their lives on material things. Most of her close friends were men. Because she chose to remain anonymous, her name is still not widely known. It is thought that staying anonymous helped her keep her private life as a mother and wife separate from her writing. Scholars believe her work shows what it was like to be a high-status female author in 18th-century France.

What She Wrote

Essays and Books

- De l’Amitié, 1761 (On Friendship)

- Traité des passions, 1764 (Treatise on the Passions)

- Essai pour servir à l'histoire de la putréfaction, 1766 (Essay on putrefaction)

- Histoire de mon enfance. (History of my childhood.)

- Méditations sur les tombeaux. (Meditations on tombs)

- Mélanges de littérature, de morale et de physique, 1775. (Mixture of literature, morality, and physics)

- Pensées et réflexions morales sur divers sujets, 1760, 2nd end 1766. (Moral thoughts and reflections on various subjects)

- Sur moi. (About myself)

- Traité d’ostéologie, in-fol. (Treatise on Osteology)

Translated Works

- Avis d’un Père à sa Fille, 1756. Translated from the English of George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax. (Advice from a Father to his Daughter)

- Leçons de chimie, 1759. Translation of Peter Shaw's Chemical Lectures (London: Longman, 2nd edn, 1755). (Chemistry Lessons)

- Romans traduits de l'anglois, 1761. Includes parts translated from George Lyttelton's Letters from a Persian in England and Aphra Behn's Agnes de Castro. (Novels translated from English)

- Mémoires de Mademoiselle de Falcourt. (Memoirs of Mademoiselle de Falcourt)

- Amynthon et Thérèse

- Mélanges de Poésies Anglaises, traduits en français, 1764. (Mixture of English Poetry, translated into French)

See Also

In Spanish: Geneviève Thiroux d'Arconville para niños

In Spanish: Geneviève Thiroux d'Arconville para niños

Further Reading

- Hayes, Julie Candler, ed. 2018. Marie Geneviève Charlotte Thiroux d’Arconville: Selected Philosophical, Scientific, and Autobiographical Writings. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |