Greenville Eight facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greenville Eight |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina |

|||

| Date | March 1, 1960 - September 19, 1960 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in | Integration of city libraries | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

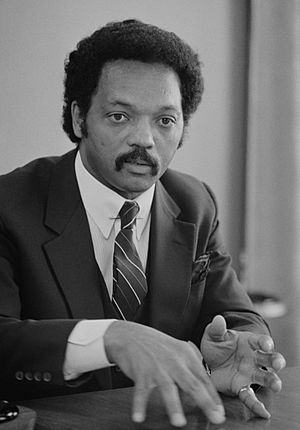

The Greenville Eight was a group of eight African American students. Seven were in high school, and one was in college. In 1960, they successfully protested against the unfair system of separate libraries for Black and white people in Greenville, South Carolina. One of the students was Jesse Jackson, who was a college freshman at the time. Because of their peaceful sit-in protest, the libraries in Greenville became open to everyone, no matter their race.

Contents

Why Libraries Were Segregated

By 1960, public libraries in other South Carolina cities like Columbia and Spartanburg had already allowed all people to use them. This happened without many problems. However, the libraries in Greenville still kept Black and white people separated.

Jesse Jackson grew up in Greenville. During his freshman year at the University of Illinois, he came home for Christmas break. He needed a book for a school paper. The book he needed was not at the "colored" library branch. This library was a small, old house with only one room. Many of its books were old and in bad shape.

The librarian at the colored branch gave Jackson a note. She told him to visit the main library, which was only for white people, because the librarian there was her friend. When Jackson arrived at the main library, he found the librarian talking with some police officers. Jackson showed the librarian the note. The book he needed was right there on the shelf. But the librarian told him he would have to wait six days to use it. Jackson tried to explain his need, but a policeman sided with the librarian. He told Jackson, "you heard what she said." Jackson was angry. He promised himself he would return in the summer to "take action" and use the library.

On March 1, 1960, twenty Black high school students went into the white-only library. They tried to use the building. To stop the protest, officials closed the library for the day. Two weeks later, seven students returned to protest the library's segregation rules. They were arrested for disorderly conduct. However, their cases never went to trial.

On July 14, Jackson and five other students stood on the library steps. Police warned them they would be arrested if they entered the building. So, the students left. A white newspaper in Charleston, South Carolina, the News and Courier, wrote about the event. It said, "Third time this year that groups of Negroes have invaded the quiet of the public library." Reverend James S. Hall Jr., who was the vice president of the Greenville NAACP, had advised Jackson. He said the whole point of the protest was to be arrested. He believed they would likely be released without more trouble after being arrested. Two days later, Jackson returned to the library with seven other students. They were all dressed neatly.

The Protest for Equal Access

On July 16, 1960, eight African American students entered the white-only public library. Seven of them were in high school, and one was in college. The eight students quietly looked at books on the shelves. Then, they sat down to read. Several white people in the library left when they saw the students protesting. A librarian immediately told the students to leave. When they refused, the librarian called the police. The sit-in lasted about 40 minutes before the police arrived. All eight protesters were arrested.

Donald J. Sampson, who was the first African-American lawyer in Greenville, arrived about fifteen minutes after the students were jailed. The court released the students after they paid a $30 bond each. They were all charged with "disorderly conduct."

What Happened Next

On July 26, 1960, lawyer Donald J. Sampson filed a lawsuit in federal court. He said the students were arrested because of unfair treatment. The NAACP organization did not agree with some of Sampson's strong words.

Facing the threat of a lawsuit, the Greenville City Council voted to close both the white and colored library branches. Greenville Mayor J. Kenneth Cass said, "The efforts made by a few Negroes to use the White library will now deprive White and Negro citizens of the benefit of a library... This same group, if allowed to continue in their self-centered purpose, may conceivably bring about a closing of all schools, parks, swimming pools and other facilities. It is difficult to see how such results could be of benefit to anyone."

Charles Cecil Wyche, a judge from the district court, dismissed the case. He said that any ruling was not important since the libraries were closed. But he warned that if the library system reopened and was still segregated, it could face "further discrimination lawsuits."

On September 19, the city quietly reopened the libraries. Many citizens had complained about the closures. The mayor did not publicly say that the libraries were integrated. He only stated, "The city libraries will be operated for the benefit of any citizen having a legitimate need for the libraries and their facilities. They will not be used for demonstrations, purposeless assembly, or propaganda purposes."

In the end, the sit-in protest by the Greenville Eight led to the library system becoming integrated. This meant everyone could use the same libraries. The charges against the students were later dropped. Other sit-in protests happened across the city in the early 1960s. Schools in Greenville also began to desegregate by the late 1960s.

The Eight Protesters

- Jesse Jackson

- Dorris Wright

- Hattie Smith Wright

- Elaine Means

- Willie Joe Wright

- Benjamin Downs

- Margaree Seawright Crosby

- Joan Mattison Daniel

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |