South Carolina in the civil rights movement facts for kids

Quick facts for kids South Carolina |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |

| Date | 1950–1970 |

| Location |

South Carolina, United States

|

| Caused by | Racial segregation in schools and public accommodations |

| Resulted in |

|

Before the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina, African Americans had very few political rights. After the American Civil War, during a time called the Reconstruction era, South Carolina briefly had a government where most leaders were Black. However, when Governor Wade Hampton III took office in 1876, things changed. He was a Democrat who did not support Black people voting.

Laws like poll taxes (paying to vote), literacy tests (reading tests), and threats stopped African Americans from voting. It was very hard to challenge the Democratic Party, which often ran elections without anyone else competing. By 1940, only about 3,000 African Americans could vote in South Carolina. This was less than 1% of those old enough to vote.

Jim Crow laws, made legal by the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, created strict separation between Black and white people across the South. African Americans could not use the same places as white Americans. Black children could not go to white schools, and their schools were often much worse. These unfair laws and voting rules were eventually changed because of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

Contents

Why the Civil Rights Movement Started

After the American Civil War, new parts were added to the United States Constitution. These were the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments. They were supposed to give African Americans in South Carolina the right to vote and be treated equally. During the Reconstruction era, South Carolina even elected many Black lawmakers. Some African Americans were elected to high positions, like Robert Smalls and Richard H. Cain in the U.S. House of Representatives.

However, in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes removed soldiers from the South. This allowed former Confederate leaders and white supremacists to take control in South Carolina. In the 1876 election, many African Americans were stopped from voting. The Republican governor, Daniel Henry Chamberlain, lost to Democrat Wade Hampton III. Over the next few decades, Black people were kept from voting using unfair tests and threats. The return of these leaders also led to the rise of groups like the Ku Klux Klan, who used fear and violence. The Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision in 1896 made it legal to separate people by race in public places and schools. This lasted until the 1960s.

In 1944, a 14-year-old Black boy named George Stinney was accused of a crime. He was questioned by police alone, without his parents or a lawyer. He was quickly found guilty by an all-white jury. His lawyer was not very helpful. George Stinney was executed on June 16, 1944. Seventy years later, in 2014, his conviction was overturned. The court said his rights were violated and his confession was likely forced.

In 1946, Isaac Woodard, a Black World War II veteran, was attacked. This happened after he was honorably discharged from the army. He was on a bus in South Carolina. The bus driver called the police, and Woodard was beaten by several white men, including police officers. He was left permanently blind. This event made many people across the country angry. President Harry S. Truman ordered an investigation. The sheriff involved was tried in court but was found not guilty by an all-white jury.

These unfair situations and laws pushed South Carolina and the nation towards the Civil Rights Movement. Many protests in South Carolina were peaceful. African American protesters were sometimes arrested or mistreated, but they usually remained nonviolent. Other states like Alabama and Mississippi often got more attention during the national movement.

Education and Schools

Public Schools

In 1951, Governor James F. Byrnes wanted to improve Black schools. He supported the idea of "separate but equal" schools, which was allowed by the Plessy v. Ferguson decision. He suggested a sales tax increase to pay for these improvements. He hoped that better Black schools would stop people from asking for schools to be integrated (mixed race).

In 1952, a court case called Briggs v. Elliott was heard. This case argued that unequal schools in Summerton, South Carolina violated the Fourteenth Amendment rights of Black children. The court agreed that unequal schools were against the law. However, it did not order schools to mix students of different races. The families appealed this decision. Briggs v. Elliott became one of five cases combined into the famous Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954. This Supreme Court decision required all schools across the country to desegregate.

By 1964, South Carolina's 37 Roman Catholic schools had desegregated. Public schools began to desegregate in August 1964. However, some schools were still separated by race into the early 1970s. The Charleston County School District started desegregating in 1963. But in the first year, only 11 Black students attended a previously all-white school. Full integration in the district did not happen until the early 1970s.

Many people who supported segregation opened private schools. These were called "segregation academies." Between 1963 and 1975, over 200 of these schools were started to keep schools all-white. For example, in Clarendon County, South Carolina, Clarendon Hall was opened in 1965. This happened after four Black students enrolled in a public school that used to be all white.

Colleges and Universities

In January 1963, Harvey Gantt became the first Black student to attend Clemson University. This happened because a judge ordered it. On May 20, 1963, over 1,000 students at the University of South Carolina protested against integration. They marched and chanted "We don't want to integrate." A cross was even burned on campus. However, in September 1963, the University of South Carolina admitted three African American students: Robert G. Anderson, Henrie Monteith Treadwell, and James L. Solomon Jr. Both Clemson and the University of South Carolina desegregated without much trouble.

The College of Charleston initially refused to follow the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This law said colleges could not refuse Black students. In July 1965, the government stopped federal loans for students at the college because it was not integrated. In 1967, the College of Charleston finally enrolled its first Black students.

Role of Black Colleges in Protests

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) played a big role in the Civil Rights Movement. In February 1960, students at Allen University and Benedict College in Columbia started planning protests. On March 2, about 50 students from these schools held sit-ins at lunch counters. This forced businesses to close. The next day, 500 students gathered to protest, and 200 marched to the city center.

On March 4, some white men burned a cross at Allen University and threw bricks at a school building. In response, the Mayor of Columbia said anyone protesting would be arrested. Students from Allen and Benedict often met in churches to plan. They made flyers to get more support for civil rights.

On March 5, students from Claflin University and South Carolina State University in Orangeburg formed the South Carolina Student Movement Association (SCSM). Their goal was to unite Black schools across the state. They wanted to protest businesses with unfair rules. On March 15, the SCSM held protests in Orangeburg, Columbia, and Rock Hill. In Orangeburg, about 1,000 students protested peacefully. Police used fire hoses and tear gas, and 388 students were arrested. Some were held in outdoor animal pens because the jail was full.

The SCSM continued to organize protests. Reverend Isaiah DeQuincey Newman led a march to the Columbia airport to protest segregated waiting rooms. He also led students to a state park to protest its all-white policy. On October 15, students at Allen University and Benedict College formed a new group to organize citywide protests.

On March 2, 1961, the NAACP in Greenville organized a large protest at the South Carolina State House. Over 200 students protested peacefully and sang hymns. Police ordered them to leave, but they refused. 187 students were arrested for "disturbing the peace." This ruling was later overturned by the Supreme Court in the case Edwards v. South Carolina (1962). Among those arrested were Reverend Newman and future U.S. Congressman Jim Clyburn.

On March 5, a Benedict College student, Lennie Glover, was hurt during a sit-in. In response, students organized an "Easter Lennie Glover No Buying Campaign." They called for daily picketing and boycotting of businesses that discriminated. Most businesses and places protested by HBCU students became desegregated within four years.

Protests and Desegregation of Public Places

From the end of the Reconstruction era until the end of the Civil Rights Movement, almost every business and public place in South Carolina was segregated. This was true by both custom and law. For example, in Greenville, a business owner could be fined for serving a white person and a Black person at the same table.

Segregation laws were in nearly every town and city. They affected daily shopping, restaurants, buses, movie theaters, airports, libraries, parks, swimming pools, restrooms, drinking fountains, and even doctors' offices.

Columbia Bus System

On June 22, 1954, Sarah Mae Flemming sat in the whites-only section of a city bus in Columbia. The bus driver told her to stand and wait for a seat in the "colored" section. When Flemming tried to get off the bus, the driver blocked her way and attacked her. Flemming was not arrested, but she went to the hospital. The next week, Modjeska Monteith Simkins heard about it and helped Flemming sue the bus company. Flemming's lawyer argued that her Fourteenth Amendment rights were violated.

Lower courts sided with the bus company. But Flemming's lawyer took the case to a federal court. Flemming won, and the court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional. This case did not get much attention at the time.

New Year's Day March

In October 1959, Major League Baseball player Jackie Robinson entered the whites-only waiting room at the Greenville Municipal Airport. Police asked him to leave, but he refused. They did not force him to move. Later, at a NAACP speech in Greenville, Robinson encouraged Black citizens to vote and protest unfair treatment. The following January, on New Year's Day, about 1,000 people marched to the airport. The airport was desegregated soon after.

Friendship Nine

In 1961, nine African American men were arrested for a sit-in. They sat at a segregated lunch counter at McCrory's in Rock Hill. This group became known as the "Friendship Nine" because they were students at Friendship College. They gained national attention and inspired many other sit-ins. A main goal of their "Jail, No Bail" protests was to fill up the prisons and force integration.

Greenville Eight

Public libraries in Columbia and Spartanburg desegregated without problems. However, in Greenville, on July 16, 1960, eight African American students protested the segregated library. The county library had separate branches for white and Black people. The Black branch was a small room with fewer books. The students entered the white branch. Some picked books and sat to read, while others looked at shelves. The librarian asked them to leave, but they stayed silent. When police arrived, the eight students were arrested.

Their lawyer sued the library system. On September 2, the mayor and city council closed the library to avoid integration. The mayor said that the efforts by a few Black people to use the white library would now stop everyone from using it. Public pressure made the mayor reopen the library, but he still refused to integrate it. However, the library desegregated soon after, and the charges against the students were dropped.

Peterson v. City of Greenville (1962)

In 1962, ten African American protesters in Greenville sat at a lunch counter reserved for white people. The manager called the police. When the protesters refused to move, they were arrested for "trespassing." The case went to the Supreme Court as Peterson v. City of Greenville (1962). The court ruled in favor of the protesters. It said that the city's segregation law violated their Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Orangeburg Massacre

On February 8, 1963, in Orangeburg, three South Carolina State University students were killed. Dozens were wounded after 200 students protested racial segregation at a local bowling alley. Highway patrolmen fired on the students. This event became known as the Orangeburg massacre. In response, South Carolina State University students protested at the State House in March.

South Carolina Public Parks and Entertainment

The court case Brown v. South Carolina State Forestry Commission (1963) ruled that all public parks must desegregate. Instead, the Forestry Commission closed all parks. They refused to open them. Parks reopened with some limits in June 1964, almost a year later. They fully reopened in July 1964.

In December 1963, five movie theaters in Columbia agreed to allow one Black couple daily. They announced they would fully desegregate by the end of January 1964. In 1961, eight Black men and women were arrested for trying to use an all-white skating rink and swimming pool in Greenville's Cleveland Park. In 1962, a federal court ruled that separating people in the park facilities was against the law. Instead of integrating, the city closed the park and the rink permanently. The pool was turned into a "Marineland" with sea lions. In 1973, the South Carolina State Fair fully integrated.

Charleston Hospital Strike

On March 17, 1969, about 300 African American women healthcare workers protested. They worked at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. They were protesting unfair pay and unsafe working conditions. Coretta Scott King, the wife of Martin Luther King Jr., joined the protesting women. This was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's first big campaign since King's death.

Some women took over the hospital president's office, singing and chanting. Most women went back to work when the Police Chief threatened to arrest them. But twelve women were fired for leaving their patients. After these firings, many more employees, mostly women, went on strike. The strike lasted over 100 days. In late April, National Guard troops arrived with tanks and rifles. The strike ended peacefully in June with an agreement.

Opposition to Civil Rights

In 1956, U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina wrote the Southern Manifesto. This document criticized the 1954 Brown v. Board decision. It called anti-segregationists "agitators and troublemakers." Many schools and districts then refused to integrate as the Supreme Court ordered. The manifesto encouraged white families to leave public schools and attend private ones.

Governor Fritz Hollings (1959–1963) first opposed integration. But he changed his mind during his time as governor. Hollings supported school integration "with dignity." He said that the time of segregation was over. Hollings was the first South Carolina governor to support integration since the Reconstruction era in the 1870s.

In 1962, the South Carolina General Assembly voted to display the Virginia battle flag on top of the State House dome. The flag flew there until 2000. It was then moved to a monument on the capitol grounds. The flag was removed from the grounds in 2015 after the Charleston church shooting.

After the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, South Carolina argued it was unconstitutional. The state said it had the right to control its own elections. But in the Supreme Court case South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), the court ruled against South Carolina. Justice Earl Warren wrote that preventing racial discrimination was a "legitimate response" by Congress.

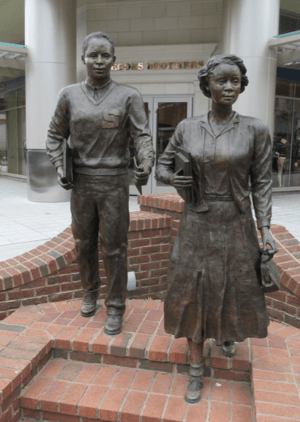

In 1967, Sterling High School, an all-Black school in Greenville, was destroyed by fire. Many believed the fire was set on purpose, especially since the school was approved for renovations that same week. However, this was never proven. In the early 1960s, students at Sterling protested unfair treatment in Greenville through peaceful protests and sit-ins. In 2006, a memorial to these students was built in Greenville.

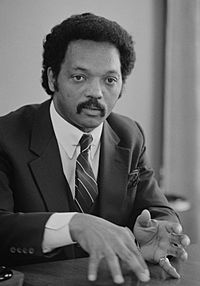

On January 25, 1972, the Springfield Baptist Church in Greenville, a Black church, was burned. This was done to oppose equality for African Americans. The church, founded by former slaves in 1867, was a safe place for African Americans during the Jim Crow era. Many civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Jesse Jackson, spoke there. It was also where many peaceful protests were planned, like the New Year's Day March that led to the desegregation of the Greenville–Spartanburg International Airport.

National Leaders and Legacy

On April 17, 1963, Malcolm X gave a speech in Columbia. He spoke against political leaders. On April 25, 1963, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy spoke at the University of South Carolina. He said that the world needed the government to do everything possible to end racial discrimination. In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech in Charleston. He encouraged African Americans to vote and protest racial inequality.

Important leaders from South Carolina include:

- Modjeska Monteith Simkins

- Isaiah DeQuincey Newman

- Matthew J. Perry

- Septima Poinsette Clark

- Jesse Jackson

- Charlayne Hunter-Gault

- Leola C. Robinson-Simpson

The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a major step. It led to the creation of the Legislative Black Caucus in the South Carolina legislature. For the first time since the Reconstruction era, African Americans were elected to political offices in South Carolina. By the end of the 1960s, more African Americans were elected to office. As of 2020, about 26% of the members of the South Carolina General Assembly were African American.

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |