Haisla language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Haisla |

|

|---|---|

| X̄a'islak̓ala, X̌àh̓isl̩ak̓ala | |

| Region | Central British Columbia coast inlet, Douglas Channel head, near Kitimat |

| Ethnicity | 1,680 Haisla people (2014, FPCC) |

| Native speakers | 240 (2014, FPCC)e18 |

| Language family |

Wakashan

|

| Dialects |

Kitamaat

Kitlope

|

|

|

The Haisla language, also known as X̄a'islak̓ala or X̌àh̓isl̩ak̓ala, is a special language spoken by the Haisla people. They are a First Nations group living on the North Coast of British Columbia, a province in Canada. Their main village is called Kitamaat.

Kitamaat village is about 10 kilometers from the town of Kitimat. This area is at the end of the Douglas Channel, which is a long, narrow sea inlet (a fjord) that stretches for 120 kilometers. This waterway is important for the Haisla people and for the aluminum factory and port in Kitimat.

In the past, the Haisla language and the languages of their neighbors, the Heiltsuk and Wuikinuxv peoples, were sometimes wrongly grouped together as "Northern Kwakiutl."

The name Haisla comes from the Haisla words x̣àʼisla or x̣àʼisəla. These words mean 'dwellers downriver', which describes where the Haisla people live.

Haisla is part of the Northern Wakashan language family. Only a few hundred people speak Haisla today. It is the northernmost language in the Wakashan family. Its closest language relative is Oowekyala.

Contents

Haisla Language Dialects

The people living in Kitamaat village today came from different places. Because of this, they had slight differences in how they spoke Haisla. The two main ways of speaking Haisla are called Kitimaat (X̅aʼislakʼala) and Kitlope (X̅enaksialakʼala). How words are said, grammar rules, and word choices can change depending on which dialect is being used.

Even with these differences, Haisla is still used as the name for the language as a whole. This is similar to how "English" includes many different dialects spoken around the world.

Sounds of Haisla (Phonology)

Haisla is closely related to other Northern Wakashan languages like Oowekyala, Heiltsuk, and Kwak'wala. It also has some links to Nuuchahnulth (Nootka), Nitinat, and Makah.

Like many languages from the Northwest Coast, Haisla has many consonant sounds. These sounds don't change much when spoken. Haisla has a wide range of consonant sounds, but not many different vowel sounds. The vowels in Haisla are similar to those in Kwakwala, but different from Southern Wakashan languages.

How Haisla Words Are Built (Morphology)

Haisla is a VSO language. This means that in a sentence, the verb (the action word) comes first, then the subject (who or what is doing the action), and then the object (who or what the action is done to). For example, instead of "The boy eats the apple," it would be "Eats the boy the apple."

Haisla is also a "polysynthetic" language. This means that words are often very long and complex. They are built from a single main part (a root) and then expanded with many endings or by repeating parts of the word. These words can be changed even more by adding other endings that show meaning or grammar, or by adding small words called "clitics."

For example, the Haisla word for 'condition' is ḡʷailas. You can change it to mean 'your condition' by adding an ending, making it ḡʷailas-us. To say 'my condition', you would add a different ending, making it ḡʷailas-genc.

Most root words in Haisla cannot stand alone as complete words. If they can, their meaning often changes. For instance, the root bekʷ can mean 'Sasquatch' when combined with the ending -es, or 'talk' when combined with -ala.

Haisla, like all Wakashan languages, uses special small words called "clitics" that attach to the first word in a sentence. These clitics help show things like when something happened (past, present, future) or if an action is complete or ongoing.

Number and Person in Haisla

Haisla language uses first person (I, we), second person (you), and third person (he, she, it, they). It also has ways to show if something is singular (one) or plural (more than one). However, Haisla doesn't always focus on whether something is singular or plural. For example, the word begʷánem can mean both 'people' and 'person' depending on how it's used.

Haisla also has special endings that show if "we" or "us" includes the person you are talking to (inclusive) or not (exclusive). This is a unique feature. Also, Haisla uses gender-neutral pronouns, meaning there's no difference between 'him' and 'her'.

How Haisla Shows Possession

In Haisla, showing who owns something often involves adding endings to words. These endings are also used with certain verbs that describe feelings or thoughts.

Sometimes, Haisla possessive endings are similar to how we use "my" in English. For example, the ending -nis can be used like "my" when placed before the object that is owned. You can also add endings directly to individual words to show possession, like gúxʷgenc which means "my house here." Haisla has many different endings to show possession.

Location and Visibility (Deixis)

In Haisla, where a conversation happens can change how the language is used. Depending on whether something happened right where you are, far away, or just left, different verb endings are used to show the location of the action.

There are four main locations in Haisla:

- Here: Near the person speaking.

- There (near you): Near the person being spoken to.

- There (remote): Far from both the speaker and the listener.

- Just gone: Something that was just there but is now gone.

These ideas help to describe the time and place of actions in Haisla. The language also tells the difference between things that are seen and known (called "visible") and things that are not seen, or are only imagined or possible (called "invisible").

Haisla also has optional small words called "demonstrative clitics," like qu and qi. These help to make the location of something in a sentence even clearer.

For example:

Duqʷel

see

John-di

John-gone

qi

RVIS

w̓ac̓i.

dog

acx̄i

RVIS

"John saw the dog"

Language Contact and Haisla (Sociolinguistics)

Because many different language groups lived on the Northwest Coast, there was a lot of talking and trading between them. This led to the creation of a special "trade language" called Chinook Jargon. Haisla adopted many words from this trade language, such as gʷasáu, which means 'pig'. Other words, like lepláit ~ lilepláit, meaning 'minister' or 'priest', show how contact with missionaries influenced the language. Most of the words adopted were for new objects or ideas. Older Haisla words, like gewedén for 'horse', were not replaced.

Haisla Language Status and Revitalization

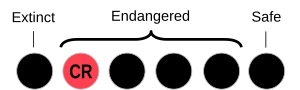

Like other languages in the Northern Wakashan family, Haisla is currently an endangered language. This means that fewer and fewer people are speaking it.

The languages of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia were greatly affected by residential schools. These schools, which were common in the 1930s, often stopped children from speaking their traditional languages. Also, after Europeans arrived, diseases greatly reduced the number of Haisla speakers.

However, there are now programs to help people learn and speak Haisla. Kitamaat village offers lessons for those who want to learn the language. Eden Robinson, an author who is Heiltsuk and Haisla, has written and spoken a lot about bringing languages back to life. She recently gave a lecture at Carleton University about this important topic.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma haisla para niños

In Spanish: Idioma haisla para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |