Henry Hetherington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

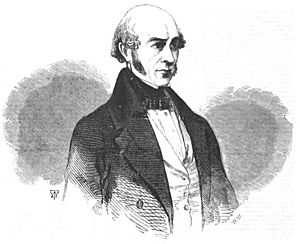

Henry Hetherington

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 1792 Soho, London, England

|

| Died | 24 August 1849 Hanover Square, London, England

|

| Resting place | Kensal Green Cemetery |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Printer and publisher |

| Employer | Luke Hansard |

| Known for | Suffragist and social activist |

| Movement | Chartism |

| Criminal charge(s) | Blasphemy; non-payment of stamp duty |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Thomas (1811–?) |

| Children | 9 |

Henry Hetherington (born June 1792 – died 24 August 1849) was an English printer and publisher. He was a champion for fairness and freedom in society. He fought for a free press, meaning newspapers could print what they wanted. He also wanted everyone to have the right to vote.

Henry worked with friends like William Lovett and James Watson. Together, they were part of many groups that wanted to make life better for working people. He was famous for publishing The Poor Man's Guardian. This newspaper helped lead a big fight against taxes on newspapers. He was even sent to prison three times for refusing to pay these taxes. Henry was also a key leader in the Chartist movement, which pushed for more democratic rights. His name is honored on a special memorial in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Contents

Henry Hetherington's Life Story

Early Years and Training

Henry Hetherington was born in June 1792 in London, England. His father was a tailor. When Henry was 13, he started learning to be a printer. He worked for Luke Hansard, who printed important government documents.

In 1811, Henry married Elizabeth Thomas from Wales. They had nine children, but sadly, only one son, David, lived longer than Henry. After his training, it was hard to find work. So, Henry worked as a printer in Ghent, Belgium, for a few years. He then returned to London around 1815.

Working for Change

In the 1820s, Henry started his own printing and publishing business. He also joined many groups that wanted to improve society. These groups aimed to help working men get an education and gain the right to vote. Through these groups, he became good friends with William Lovett and James Watson. They worked together for many years.

Henry was inspired by the ideas of Robert Owen, who believed in people working together. Henry helped start a co-operative society. These groups encouraged people to trade together and even tried to set up communities where everyone shared.

In 1822, Henry set up his own printing shop in London. His first publication was a journal about economics and helping people. He also joined the London Mechanics Institute. This place offered education to working-class men. He met Lovett and Watson there.

Later, Henry helped create the British Association for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge. This group helped new co-operative societies and taught people about working together. Henry became a great speaker for this movement.

Henry and his friends believed that working together wasn't enough. They also needed political rights. They joined groups that fought for things like the right to vote for all men. This included the National Union of the Working Classes.

Some leaders, like Robert Owen, thought politics were not important for co-operation. But Henry disagreed. He believed that getting political rights was very important. So, he focused on fighting for the right to vote and for a free press.

The "War of the Unstamped"

Back then, the government wanted to stop working-class people from reading radical ideas. So, they put a high tax on newspapers. This tax, called "stamp duty," made newspapers very expensive. Only rich people could afford them.

But in 1830, things changed. People wanted more freedom, especially after a revolution in France. Henry Hetherington decided to publish a newspaper without paying the tax. He called it The Penny Papers for the People. This started what was known as the "War of the Unstamped."

Between 1830 and 1836, many newspapers were published without paying the tax. Hundreds of people were arrested for selling them. Henry published several of these papers. His most famous was The Poor Man's Guardian. Its front page proudly said it was "Established Contrary To "Law" To Try The Power Of "Might" Against "Right"".

Henry didn't write the articles himself. He had other writers do that. Instead, he traveled around the country. He gave speeches, telling people that the government's new voting laws didn't include working-class people. He also spoke out against the lack of press freedom. He also helped set up ways to get his newspapers to people.

Because he was so well-known, the government targeted him. He was sent to prison three times. He was also fined, and his printing machines were taken away. But Henry always defended himself in court. His brave speeches were even sold as small booklets. He became a hero to his readers. At its peak, The Poor Man's Guardian sold about 15,000 copies per issue. Many more people read each copy.

In 1836, the government lowered the newspaper tax. But they also made it much harder for unstamped papers to exist. Henry had to change his unstamped Twopenny Dispatch into a taxed paper. He told his readers that personal bravery wasn't enough against the government's new rules.

The Chartist Movement

Henry stayed active in politics. He joined William Lovett's London Working Men's Association (LWMA). This group was mostly made up of skilled workers. They believed in improving working-class lives through education. They held discussions, did research, and organized public meetings.

In 1837, one of their meetings led to the creation of the People's Charter. This document asked for changes to Parliament, like the right for all men to vote. The movement to achieve these goals became known as Chartism.

Henry and other speakers traveled the country. They promoted the idea of everyone having the right to vote. They encouraged local groups to join the Chartist cause. Henry was chosen as a delegate to a big Chartist meeting in 1839. This meeting planned how to present their petition to Parliament. It also discussed what to do if their requests were rejected.

Henry and other LWMA members believed in peaceful change. They were part of the "moral-force" Chartism. This meant they wanted to achieve their goals through education and peaceful actions. This put them at odds with some other Chartists who believed in using "physical force" if needed.

This disagreement caused a split in the movement. Henry and his friends formed a new group. They wanted to achieve the Charter through education and self-improvement. Other Chartists, like Feargus O'Connor, called them traitors. Despite Henry's protests, he and his group became separated from the main Chartist movement.

Later Life and Beliefs

Henry stayed involved in his new group for several years. But it was small. So, he started focusing on other important issues. These included religious freethought and international politics.

Henry had been interested in freethought since the 1820s. This meant questioning traditional religious ideas. In 1840, he was even imprisoned for publishing a book that was considered "blasphemous" (against religious teachings). In 1846, his strong belief in freethought caused a disagreement with Lovett. Henry then joined the atheist George Holyoake at a different institution.

Henry also reconnected with Robert Owen's ideas about social progress. He helped form the League of Social Progress in 1848.

He also supported movements for democracy in other countries. He helped form the Democratic Friends of All Nations. He also joined Giuseppe Mazzini's Peoples' International League.

Henry never gave up on the Charter. In 1848, he helped start the People's Charter Union. This group also believed in peaceful change. It didn't last long, and many of its members, including Henry, went back to fighting for a free press. They formed the Newspaper Stamp Abolition Committee.

His Final Days

Henry Hetherington became sick with cholera in August 1849. He believed his healthy lifestyle would protect him, so he refused medicine. He passed away in London on August 24, 1849, at the age of 57.

In his will, he stated his beliefs. He confirmed he was an atheist and supported Robert Owen's ideas. He also wrote that it was "the duty of every man to leave the world better than he found it." About two thousand people attended his non-religious funeral at Kensal Green Cemetery.

In 1885, a special monument called the Reformers' Memorial was put up in the cemetery. Henry Hetherington's name is included on it.

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |