History of Hamilton, Ontario facts for kids

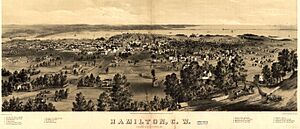

Hamilton, Ontario, has always been a special place because of its great location near important travel routes like the Niagara Peninsula and Lake Ontario. This made it a key spot in Canada, especially for its history with the military.

Even from the start, people in Hamilton tried to balance growing the economy with protecting nature. The area near Burlington Bay (also called Hamilton Harbour) and the Niagara Escarpment has changed a lot for homes, factories, and fun activities. Cootes Paradise, a wetland in Dundas, was once full of fish, birds, and other animals. It was named after Captain Thomas Coote, a British army officer. Even though it was used a lot, people started protecting it in the 1880s. Today, it's still a very important natural area.

For about 100 years after becoming a city in 1846, Hamilton was known for its factories. It earned nicknames like The Ambitious City, Steel City, and the Birmingham of Canada. But later, other types of businesses grew, and Hamilton became a "post-industrial" city. However, its image didn't quite catch up. This article will explore how Hamilton grew until the end of the Second World War.

Before European settlers arrived, the Hamilton area was home to the Chonnonton, or Attiwandaronk, an Iroquois-speaking group known as the "Neutral" people by French explorers. Since then, many different groups of people have moved to Hamilton.

Contents

Early Days: Before 1811

Like much of North America, the Hamilton area was first home to Indigenous peoples. The first European to visit was likely Étienne Brûlé in 1616. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, also visited, and there's a park in Burlington that remembers him.

The Neutral Nation lived in most of the land before settlers arrived. But they were slowly pushed out by the Iroquois. The Iroquois were allies with the British against the French and their Huron allies. An Iroquois leader helped create the path and name for Mohawk Road on Hamilton Mountain. This path also led to what became King Street in the lower city.

The American Revolution divided the Six Nations confederacy, just like it divided British North America. Indigenous groups who supported the British Crown, led by Captain Joseph Brant, settled in areas near Hamilton. These included Brant’s Ford (now Brantford) and Brant’s Block (now Burlington).

Many United Empire Loyalists also moved to the Hamilton area during and after the American War of Independence. This greatly increased the population and helped the region grow. This was very important because the fighting between the United States and Britain wasn't over yet.

Administratively, the area was first part of the Nassau District, which changed to the Home District in 1792. Later, parts of the area became part of Niagara District and Lincoln County.

Growing Up: 1812 to 1844

The idea for the town of Hamilton came from George Hamilton. He bought a farm after the War of 1812. Nathaniel Hughson, another landowner, worked with George Hamilton to suggest building a courthouse and jail on Hamilton's land. Hamilton offered his land to the government for this purpose. James Durand, a local politician, helped sell the land that would become the town. A new Gore District was created, and Hamilton was part of it.

At first, Hamilton wasn't the most important place in the Gore District. A permanent jail wasn't built until 1832. The town limits and its first police board were officially set on February 13, 1833.

When the War of 1812 broke out, the Hamilton area became a key location again. In 1813, British soldiers and Canadian militia beat American troops at the Battle of Stoney Creek. This battle happened in what is now a park in eastern Hamilton. Burlington Heights, near Dundurn Park, was also an important spot overlooking Burlington Bay.

George Hamilton, a settler and politician, started a town in Barton Township in 1815 after the war. He kept some east-west roads that were old Indigenous trails. But the north-south streets were laid out in a straight grid pattern. Streets were named "East" or "West" if they crossed James Street. They were named "North" or "South" if they crossed King Street.

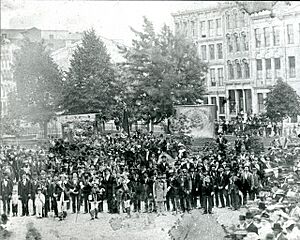

Gore Park, located at King and James Streets, became the main public square for the new settlement. It has been the city's center ever since. The land set aside for the courthouse has had four different buildings on it.

The Gore District and Wentworth County were created in 1816, with Hamilton as their main center. The county included townships like Ancaster, Barton, Binbrook, Glanford, and Saltfleet. These areas later became part of the larger Hamilton in 2001.

During the early 1800s, Hamilton grew steadily, becoming more important than Dundas. Its growth was helped in 1810 when a channel was dug to connect Burlington Bay directly to Lake Ontario. This made water transportation much better. George Hamilton’s settlement became an official police village in 1833. You can see what these pioneer days were like at the Westfield Heritage Centre.

People in Hamilton got excited about railways in the 1830s. Allan MacNab's Hamilton and Port Dover Railway was planned in 1835, but tracks weren't laid until the 1850s. MacNab finished his grand home, Dundurn Castle, in 1835. He was a young soldier in the War of 1812. He later led the local militia to stop a rebellion in 1837 and was knighted for it.

City Life Begins: 1845 to 1866

Hamilton officially became a city on June 9, 1846.

As the city grew, its government changed. Hamilton City Council was run by a "board of control," which was like a main committee of city councilors. Mayors often changed almost every year. In the same year Hamilton became a city, Robert Smiley started publishing The Hamilton Spectator newspaper.

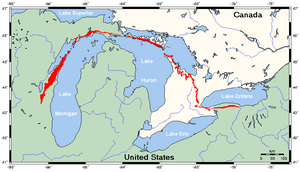

When Allan MacNab finished his time as premier of the Province of Canada, the Great Western Railway became Hamilton’s first working railway in 1854. This railway and the Niagara Suspension Bridge made Hamilton a major hub. It became part of the immigration route from New York City or Boston to Chicago or Milwaukee. Traveling through what was then called CANADA WEST saved over 200 miles. However, because the American and Canadian tracks had different widths, passengers had to switch trains at Niagara Falls and Detroit. The railway’s repair yards were in Hamilton, giving the city its first taste of the steel industry. Sadly, in 1857, 57 passengers died when a train crashed near the Desjardins Canal.

Hamilton wasn't content with just small operations. Many small workshops and craftspeople joined together to make steel, not just shape it. It was easy to get limestone from the Niagara Escarpment, coal from Appalachia, and iron ore from the Canadian Shield. Plus, it was easy to ship goods through the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. All this made Hamilton an important city for producing iron and steel.

Other businesses in the Ambitious City (a name given by people in Toronto) and Birmingham of Canada included making tobacco, beer, and other products. It also became a center for the textile industry, which made fabrics and clothes.

Before the Royal Military College of Canada was built in 1876, there were ideas for military colleges in Canada. British soldiers taught a three-month military course in Hamilton starting in 1865. This school helped officers and future officers learn military duties and discipline. The school closed after Canada became a country in 1867.

A New Nation: 1867 to 1892

When Canada became a country in 1867, Hamilton was excited to be part of it. The city had one seat in the Canadian Parliament, and the rest of the county had two.

More businesses and factories meant more people moved to Hamilton, especially from the British Isles. Many Irish immigrants created a "Corktown" neighborhood near John and Hunter Streets. People who loved Britain and Canadians of British background built many monuments downtown. These honored important figures like John A. Macdonald, Queen Victoria, and the United Empire Loyalists. More people meant more demand for services. In 1874, the Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) started offering public transportation with horse-drawn vehicles.

Robert Smiley, who started The Spectator newspaper, sold it to William Southam in 1877. This was the first step in creating the Southam newspaper chain. In 1879, a unified, paid Hamilton Fire Department replaced the many volunteer fire companies.

The Hamilton area was also important in the early history of the telephone. Alexander Graham Bell thought of the telephone idea in 1874 while staying at his parents’ home in Brantford. He made the first experimental long-distance call to Paris, Ontario, in 1876. The next year, Thomas Peter Henderson became the first General Agent for the telephone business in Canada. In 1878, the first telephone exchange in the British Empire opened in Hamilton, started by Hugh Cossart Baker, Jr. On May 15, 1879, Hamilton became the site of the first commercial long-distance telephone line in the British Empire.

More workers and new immigrants led to the start of trade unions for skilled workers. Hamilton union members and other working-class people started the Nine Hour Movement in 1872. They wanted the government to limit working hours to nine per day.

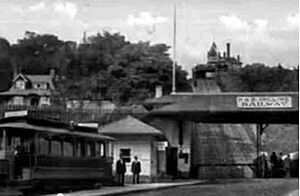

A smaller railway boom happened in the late 1800s. The Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway was created in 1884. By 1892, it offered cargo service and later passenger service. Electric railways that connected Hamilton with Grimsby, Beamsville, Brantford, and Oakville were built in the next decade.

New Century, New Changes: 1893 to 1905

Modernization and business growth often went hand-in-hand with unions forming. The Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) switched from horse-drawn vehicles to electric-powered ones in 1892. The firefighters formed a union in 1896. When the HSR was bought by the Hamilton Electric Light and Power Company in 1899, HSR workers joined a union that is now part of the Amalgamated Transit Union.

But it wasn't all work for local residents. In 1894, Billy Carroll, a newspaper owner, started the Around the Bay Road Race. This race goes around Burlington Bay. Even though it's not a full marathon, it's the longest continuously held long-distance foot race in North America. Famous runners like William "Billy" Sherring, Tom Longboat, and Sam Mellor won it.

Adelaide Hoodless and others started the first Women’s Institute in Saltfleet Township (Stoney Creek) in 1897. She began teaching about home economics. A school in Hamilton was named after her after she passed away in 1910.

Hamiltonians, like others in the British colonies, saw a difficult side of British Imperialism when the South African War started in 1899. Men from Wentworth County and other Canadians volunteered to serve. The war ended in 1902.

Ernest D’Israeli Smith started a company in 1882 to sell his fruit directly to stores, cutting out the middleman. Smith & Sons Ltd. still operates today, selling jams and preserves since the early 1900s. Its founder was a Conservative Member of Parliament for Wentworth.

By the end of the 1800s, Hamilton had grown to its approximate limits. This included the Mountain Brow to the south, Chedoke Creek to the west, and Gage Avenue to the east.

As the population grew, the balance between urban Hamilton and rural Wentworth shifted. In 1904, the federal voting areas were changed. Two Members of Parliament were now from the city itself (Hamilton East and Hamilton West), and one represented the rest of the county.

A New Era: 1906 to 1918

Hamilton had a very important year in 1906. Local boy Billy Sherring won an Olympic gold medal in Athens for the marathon race. The Amalgamated Transit Union went on strike against the HSR in a difficult labor dispute. Working-class voters in Hamilton East, who supported the union, elected Allan Studholme as their Member of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. For years, he was the only labor representative in the legislature. He fought for the eight-hour day, workers' compensation, a minimum wage, and women's right to vote.

The steel industry continued to grow and combine during this time. Some companies joined to form the Steel Company of Canada (Stelco) in 1910. Others formed the Dominion Steel Casting Company (Dofasco) in 1912. Stelco and Dofasco were located in the north end to use the water for transportation and cooling. Unfortunately, waste from these industries made Hamilton Harbour very polluted.

Hamilton's radial railway system became more connected. In 1907–08, the company that owned the interurban railways changed its name to the Dominion Power and Transmission Company. It opened a new main station downtown, the Hamilton Terminal Station. Passenger services were reorganized so that all lines met there. This allowed people to travel long distances, like from Oakville to Brantford, without changing trains.

The new science of aviation found early supporters in Hamilton. Jack Elliot built an airport near Stelco in the north end. In 1911, it hosted the first Canadian Air Meet. Pioneering aviator J.A.D. McCurdy won that contest.

People continued to move from Britain and the United States (especially African Americans) during this time. But immigrants also started coming from other countries like Italy and Austria-Hungary. Many Italian Hamiltonians today are descendants of immigrants from a single Sicilian town. This is remembered by Murray Street also being called Corso Raculmuto.

More people and prosperity led to a building boom. As a publicity stunt, workers built a house in one day in 1913. This was later featured in a Ripley's Believe It or Not! cartoon. In the same year, the Hamilton Public Library opened its new building, funded by Andrew Carnegie.

Hamiltonians participated in the First World War as soldiers. The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry later carried on the battle honors of four Canadian battalions.

Heavy industry boomed as the Canadian and British governments needed more steel, weapons, ammunition, and textiles for the war. Unfortunately, in their rush to expand, the steel companies damaged the land. They filled in parts of Hamilton Harbour and buried or moved many creeks that flowed into the bay.

Between Wars: 1919 to 1938

The United Farmers of Ontario won the most seats in the 1919 provincial election. They formed a government with the Independent Labour Party. Walter Rollo, a politician from Hamilton West, became Ontario's first Minister of Labour in this government.

The Hamilton Board of Education started building many new schools again. Their names often honored war veterans, like Memorial School, Allenby School, and Earl Kitchener School. This school building boom happened at the same time as a housing boom. Hundreds of low-rise apartment buildings were built across the city, especially in the east end.

Higher education came to Hamilton in 1930 with McMaster University. It was founded in Toronto as a Baptist university in 1887. Hamilton's city government and residents worked hard to bring the university to the city with land and money in 1930. McMaster kept its independence and started publishing its student newspaper, The Silhouette.

Local supporters also made sure Hamilton hosted the first Empire Games in 1930. These games are now known as the Commonwealth Games. Athletes from across the British Empire gathered to compete at Hamilton Civic Stadium, thanks to the efforts of Melville Marks Robinson.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit Hamilton hard. The long decline in people buying goods and in international trade stopped construction for a decade.

People found emotional relief from the Depression through the Washingtons, local brothers who performed as a blues quartet. Practical help came from government projects designed to boost the economy. These projects also made Hamilton more attractive in the long run.

Thomas B. McQuesten, a Hamilton lawyer and politician, was the minister of transportation from 1934 to 1943. He led the building of the Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW), a highway connecting Fort Erie with Toronto through Hamilton. He also helped build the Mountain access for Highway 20 in Stoney Creek. He founded the Royal Botanical Gardens, seeing it grow from an idea in the 1920s to a staffed institution in the 1940s. His family home, Whitehern, is now a city museum.

War and Change: 1939 to 1945

In the Second World War, Britain wanted to strengthen its support from countries like Canada. When King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited Canada in May and June 1939, they stopped in Hamilton and also opened the QEW.

Hamiltonians, like others around the world, welcomed the increase in economic activity caused by the war, but not its reason. Heavy industry again released pollutants. By the end of the war, the environment in Hamilton had suffered. Heavy metals made fish from Hamilton Harbour unsafe to eat, air pollution made breathing difficult, and industrial waste contaminated the land.

Unlike the First World War, in this war, the Canadian Army sent its local militia units as a whole. Men of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (known as the Rileys) and the rest of the 2nd Canadian Division were called up early. The Hamilton area was also active in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). The city helped fund 424 "Tiger" Squadron by buying bombers for it.

On the home front, people eagerly followed the war's progress. They also got to see airmen in action. In 1940, the Royal Canadian Air Force set up a station in Glanford Township as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Hundreds of pilots and aircrew from Commonwealth countries were trained at RCAF Station Mount Hope.

The army's long wait led to unhappiness among soldiers, the public, and the government. In this situation, Lord Louis Mountbatten planned an attack called the Dieppe Raid. The Rileys lost hundreds of their young men in one day in 1942, almost wiping them out as a fighting force at Dieppe. In 1943, the Hamilton Parks Police, a special police force, was created.

When the war finally ended, Hamilton was a very different place. Women had permanently joined the paid workforce. The difficult times of the Great Depression were over.

Notable People from Hamilton (Before 1946)

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1816 | 668 | — |

| 1833 | 1,000 | +49.7% |

| 1841 | 3,000 | +200.0% |

| 1846 | 6,832 | +127.7% |

| 1850 | 10,248 | +50.0% |

| 1861 | 19,096 | +86.3% |

| 1871 | 26,716 | +39.9% |

| 1880 | 35,009 | +31.0% |

| 1890 | 44,643 | +27.5% |

| 1900 | 51,561 | +15.5% |

| 1910 | 70,221 | +36.2% |

| 1914 | 100,808 | +43.6% |

| 1920 | 108,143 | +7.3% |

| 1929 | 134,566 | +24.4% |

| 1939 | 155,276 | +15.4% |

| 1945 | 175,364 | +12.9% |

| 1950 | 192,125 | +9.6% |

| 1960 | 258,576 | +34.6% |

| 1970 | 296,826 | +14.8% |

| 1980 | 306,640 | +3.3% |

| 1990 | 307,160 | +0.2% |

| 2002† | 490,268 | +59.6% |

| 2006 | 504,559 | +2.9% |

| 2011 | 519,949 | +3.1% |

| Source: †2002=Post-Amalgamation. |

||

Here are some well-known people connected to Hamilton who became famous before 1946, listed by their birth year:

- Étienne Brûlé, (1592–1633), likely the first European to visit what is now Hamilton in 1616.

- Robert Land, (1736–1818), a veteran of the American Revolution and one of Hamilton's first citizens.

- John Askin, (1739–1815), a fur trader, merchant, and official in Upper Canada.

- Nathaniel Hughson, (1755–1837), a farmer and hotel owner, and one of Hamilton's city founders.

- William Rymal, (1759–1852), an early farmer on Hamilton Mountain. Rymal Road is named after him.

- Richard Beasley (1761–1842), a soldier, politician, farmer, and businessman.

- John Vincent, (1764–1848), a British army officer in the Battle of Stoney Creek during the War of 1812.

- Richard Hatt (1769–1819), a businessman, judge, and political figure.

- James Gage, (1774–1854), a lumber merchant and miller. Gage Avenue is named after him.

- James Durand, (1775–1833), a businessman and political figure.

- John Willson, (1776–1860), a judge and political figure.

- Peter Hess, (1779–1855), a farmer and landowner. Peter and Hess Streets are named after him, and Caroline Street is named after one of his daughters.

- George Hamilton, (1788–1836), a settler and city founder.

- Henry Beasley, (1793–1859), a farmer and office-holder.

- Sir Allan MacNab, (1798–1862), a soldier, lawyer, businessman, knight, and former Prime Minister of Upper Canada. MacNab Street is named after him.

- Thomas Stinson, (1798–1864), a merchant, banker, and landowner. He owned a lot of land in Hamilton and other cities.

- George Perkins Boothesby Bull, (1795–1847), a newspaper printer and publisher of an early Hamilton newspaper.

- Edward Jackson, (1799–1872), a tinware manufacturer. Jackson Street is named after him.

- Peter Hunter Hamilton, (1800–1857), a landowner and businessman, and half-brother of city founder George Hamilton. Hunter Street is named after him.

- Peter Jones, (1802-1856), an Indigenous Methodist missionary and Chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, born on the Burlington Heights.

- Colin Campbell Ferrie, (1808–1856), Hamilton's first Mayor.

- Isaac Buchanan, (1810–1883), a businessman and political figure.

- Daniel C. Gunn, (1811–1876), a dock worker and locomotive manufacturer.

- James Jolley, (1813–1892), a saddler and politician. He funded the construction of the Jolley Cut, a road up the Mountain.

- John Rae, (1813-1893), a physician and explorer who lived in Hamilton.

- Dennis Moore, (1817–1887), a tinware manufacturer.

- Hugh Cossart Baker, Sr., (1818–1859), a banker and mathematician. He started the first life insurance company in Canada in 1847.

- Richard Wanzer, (1818–1900), a sewing machine manufacturer.

- Thomas Mayne Daly Sr., (1827–1885), a businessman and politician.

- Thomas Bain, (1834–1915), Speaker of the Canadian House of Commons.

- Richard Butler, (1834–1925), an editor, publisher, and journalist. The Butler neighborhood is named after him.

- George Elias Tuckett, (1835–1900), of Tuckett Tobacco Company, and Hamilton's 27th mayor.

- James McMillan, (1838–1902), a U.S. Senator from Michigan.

- William Eli Sanford (1838–1899), a Canadian businessman, giver of gifts, and politician.

- George Washington Johnson, (1839–1917), a teacher and songwriter, famous for the poem When You and I Were Young, Maggie.

- Sir John Morison Gibson, (1842–1929), a lawyer, politician, and businessman.

- Clementina Trenholme, (1844–1918), an author and social organizer, and mother of radio pioneer Reginald Fessenden. Two Hamilton Mountain neighborhoods are named after her.

- Hugh Cossart Baker, Jr., (1846–1931), a businessman and telephone pioneer.

- William W. Cooke, (1846–1876), a military officer who fought in the American Civil War. Buried in Hamilton Cemetery.

- Allan Studholme, (1846–1919), a stove maker and the first Ontario Labour politician.

- Campbell Leckie, (1848–1925), an engineer. Leckie Park is named after him.

- Sir William Osler, (1849–1919), known as the Father of Modern Medicine.

- Robert B. Harris, (1852–1933), a businessman who started The Hamilton Herald newspaper in 1889.

- E. D. Smith, (1853–1948), a farmer, businessman, and politician.

- James Balfour , (1854–1917), an architect who designed important buildings in Hamilton and Toronto.

- Robert Kirkland Kernighan, (1854–1926), a poet and journalist. The Kernighan neighborhood is named after him.

- Robert Stanley Weir, (1856–1926), a lawyer and poet, best known for writing the English words to O Canada.

- Charles S. Wilcox, (1856–1938), the first president of the Steel Company of Canada (Stelco).

- Sir John Strathearn Hendrie, (1857–1923), Lieutenant Governor of Ontario from 1914 to 1919.

- Adam Inch, (1857–1933), a dairy farmer and politician. Inch Park is named after him.

- Andrew Ross, (1857–1941), a businessman and builder of the Tivoli Theatre.

- Adelaide Hoodless, (1858–1910), an education and women’s activist.

- John Moodie Jr., (1859–1944), an executive and hobbyist who drove the first automobile in Canada in 1898.

- Thomas Willson, (1860–1915), a Canadian inventor who designed and patented early electric arc lamps.

- Sydney Chilton Mewburn, (1863–1956), a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Militia and Defence.

- John Charles Fields, (1863–1932), a Canadian mathematician and founder of the Fields Medal, sometimes called the Nobel Prize in Mathematics.

- Helen Gregory MacGill, (1864–1947), the first woman judge of the juvenile Court in British Columbia.

- Julia Arthur, (1868–1959), a Canadian-born stage and film actress.

- Walter Rollo, the first Ontario Minister of Labour.

- John M. Lyle, (1872–1945), a Canadian architect who designed famous buildings like the New York Public Library.

- Clifton Sherman, (1872–1955), who founded Dominion Foundries and Steel (Dofasco) in 1912 with his brother Frank Sherman.

- Jean Adair, (1873–1953), an actress.

- Charles William Bell, (1876–1938), a playwright and politician.

- Florence Harvey, (1878–1968), a golf champion and founder of the Canadian Ladies Golf Association.

- William Sherring, (1878–1964), a Canadian athlete who won a gold medal in the marathon at the 1906 Summer Olympics.

- Elizabeth Bagshaw, (1881–1982), a physician and activist.

- John Christie Holland, (1882–1954), an ordained Minister who was honored as Hamilton's Citizen of the Year in 1953.

- Robert Kerr, (1882–1963), an Irish-Canadian sprinter who won gold and bronze medals at the 1908 Summer Olympics.

- Thomas Baker McQuesten, (1882–1948), a lawyer and Ontario minister of transportation.

- Frank Sherman, (1887–1967), who founded Dominion Foundries and Steel (Dofasco) in 1912 with his brother Clifton Sherman.

- Harry Crerar, (1888–1965), a Canadian general and the country's "leading field commander" in World War II.

- Douglass Dumbrille, (1889–1974), an actor and one of the Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood.

- James Lyle Telford, (1889–1960), mayor of Vancouver, B.C., from 1939 to 1940.

- Florence Lawrence, (1890–1938), Hollywood's first movie star.

- Dick Irvin Sr., (1892–1957), an NHL hockey player and former head coach of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Montreal Canadiens.

- Del Lord, (1894–1970), a film director best known for directing Three Stooges films.

- Helen Kinnear, (1894–1970), the first federally appointed woman judge in Canada.

- Frank O'Rourke, (1894–1986), a former professional MLB baseball player and long-time New York Yankees scout.

- Cecil "Babe" Dye, (1898–1962), an NHL hockey player and top goal scorer of the 1920s.

- Harold A. Rogers, (1899–1994), the founder of Kin Canada, a Canadian non-profit service organization.

- George Owen, (1901–1986), a professional hockey defenseman for the Boston Bruins.

- Robert McDonald, (1902–1956), a Canadian soccer player who played for the Scottish football club Rangers.

- John Foote, (1904–1988), a military chaplain and Ontario cabinet minister, and a Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross.

- George Klein, (1904–1992), often called "the most productive inventor in Canada in the 20th century."

- Red Horner, (1909–2005), a former professional hockey player who helped the Toronto Maple Leafs win their first Stanley Cup in 1932.

- Ray Lewis, (1910–2003), a track and field athlete, and the first Canadian-born Black Olympic medalist.

- Jackie Callura, (1914–1943), a Canadian featherweight boxer and World featherweight champion in 1943.

- Harold E. Johns, (1915–1998), a Canadian medical physicist known for his work in using radiation to treat cancer.

- Syl Apps, (1915–1998), a legendary Toronto Maple Leafs captain who led the Leafs to three Stanley Cups.

- Win Mortimer, (1919–1998), a comic book and comic strip artist for the superhero Superman.

- Leo Reise Jr., (1922-2015), a retired NHL hockey defenseman who played for Detroit, Chicago, and NY Rangers.

- John Callaghan, (1923–2004), a Canadian heart doctor who helped pioneer open-heart surgery.

Images for kids

See also

- Economic History of Hamilton, Ontario

- History of Ontario

- List of National Historic Sites of Canada in Hamilton, Ontario

- List of royal visits to Hamilton, Ontario

- Timeline of events in Hamilton, Ontario

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |