John Rae (explorer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

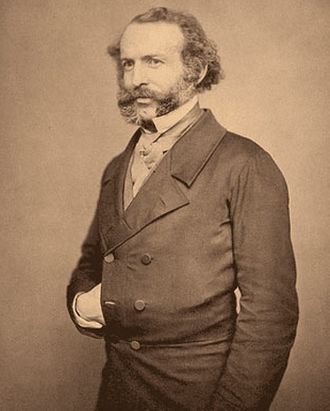

John Rae

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 30 September 1813 Hall of Clestrain, Orphir, Orkney Islands, Scotland

|

| Died | 22 July 1893 (aged 79) Kensington, London, England

|

| Burial place | St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, Scotland |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Physician, explorer, chief factor |

| Employer | Hudson's Bay Company |

| Known for | Report on the fate of Franklin's lost expedition |

| Spouse(s) |

Catherine Thompson (m. 1860)

|

| Awards |

|

John Rae (born September 30, 1813 – died July 22, 1893) was a brave Scottish explorer and surgeon. He is famous for exploring parts of northern Canada and for finding out what happened to the lost Franklin Expedition.

Rae was known for his amazing physical strength and his ability to survive in the harsh Arctic. He was skilled at hunting, handling boats, and traveling long distances with very little equipment. He learned many survival methods from the local Inuit people, which helped him live off the land.

Contents

Early Life and Training

John Rae was born in Hall of Clestrain in Orkney, a group of islands in the north of Scotland. He studied medicine in Edinburgh and became a licensed surgeon.

After his studies, he joined the Hudson's Bay Company as a surgeon. He worked at Moose Factory, Ontario, for ten years. There, he treated both European and Indigenous employees. Rae became known for his incredible endurance and his skill with snowshoes. He learned to live off the land, just like the native people. He even designed his own snowshoes with local craftsmen. This knowledge allowed him to travel huge distances with few supplies, unlike many other explorers of his time.

Exploring the Arctic

First Arctic Journey: Gulf of Boothia

In 1844, Rae was chosen to explore the northern coast of Canada. He first had to learn how to survey land. He traveled a long way, even by dog sled in winter, to find instructors.

Finally, in August 1845, Rae began his journey. He reached Repulse Bay in July 1846. Local Inuit people told him there was salt water to the northwest. This made him choose Repulse Bay as his base.

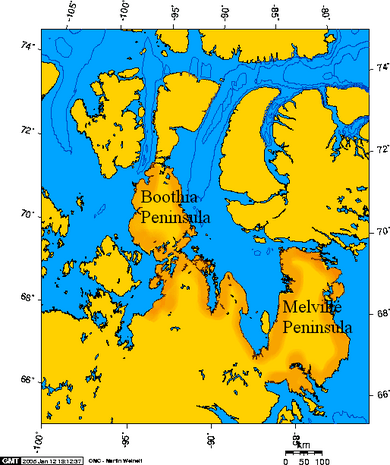

On his first trip, he dragged one of his boats 40 miles northwest to Committee Bay. Here, he learned from the Inuit that the Gulf of Boothia was a bay. He would need to cross land to reach his goal.

Rae's second journey began in April 1847. He crossed to Committee Bay and explored the area. He thought he could see Lord Mayor Bay, where another explorer, John Ross, had been trapped in ice years before. Rae learned to build igloos, finding them warmer than European tents.

His third journey started in May 1847. He hoped to reach the Fury and Hecla Strait. But bad weather and low food supplies forced him to turn back. He left Repulse Bay in August and returned to England. Even though he didn't reach his exact goal, he had explored a lot of new land.

Exploring the Arctic Coast

From 1848 to 1851, Rae made three more journeys along the Arctic coast. He explored the area around the Mackenzie River and the Coppermine River. He also tried to reach Victoria Island.

By 1848, it was clear that Sir John Franklin's expedition, which had sailed west in 1845, was lost. Three groups were sent to find them. Rae was chosen as second-in-command for one of these search parties.

First Trip: Mackenzie to Coppermine

The expedition left England in March 1848. They traveled across North America to Great Slave Lake. Rae and his leader, Sir John Richardson, went down the Mackenzie River and east along the coast. They wanted to cross to Victoria Island, but thick ice made it impossible. They had to leave their boats and travel overland to their winter camp at Fort Confidence.

Second Trip: Blocked by Ice

In December and January, Rae made trips to find a better route. In June, he left with seven men. They hauled a boat overland to the Kendall River and then to the Coppermine River. They waited for the ice to break up.

They reached Coronation Gulf in July. They tried to cross to Victoria Island but were stopped by fog and moving ice. Rae had to turn back. On their way back, their boat was lost, and their interpreter was killed.

Third Trip: Victoria Island

Rae returned to the Arctic in 1850. He had a complex plan. He would build two boats and collect supplies over winter. In spring, he would use dog sleds to cross to Victoria Island. Meanwhile, his men would haul the boats overland. Once the ice melted, he would follow the coast by boat.

On April 25, 1851, he left the fort. He crossed the frozen strait to Lady Franklin Point on Victoria Island. He explored east, naming the Richardson Islands. He then went west, exploring around Simpson Bay. He reached his furthest point on May 24, looking north across Prince Albert Sound.

He turned south, crossed the strait safely, and went inland. This part of the journey was tough due to melting snow. In June, he continued by boat down the Kendall and Coppermine rivers. He explored the south coast of Coronation Gulf and reached Cape Flinders. He then crossed to Victoria Island and explored Cambridge Bay.

He continued east along an unknown coast. The weather got worse, and he was blocked by ice. He made a final push north on foot. On August 21, he found two pieces of wood from a European ship, likely Franklin's. But Rae chose not to guess.

He returned to Fort Confidence on September 10. He had traveled over 1,000 miles on land and over 1,300 miles by boat. He mapped 630 miles of unknown coast and proved that Victoria Island was one large island. However, he still hadn't found Franklin.

The Mystery of Franklin's Expedition

In 1854, while exploring the Boothia Peninsula, Rae met some local Inuit people. They gave him important information about the fate of the Franklin expedition. His report to the British Navy contained shocking news: some survivors had resorted to cannibalism to stay alive.

When this news was shared with the public, Franklin's widow, Lady Jane Franklin, was very upset. She and others, including writer Charles Dickens, criticized Rae. They argued that British Navy sailors would never do such a thing. Dickens even suggested that the Inuit, whom he viewed negatively, might have killed the survivors.

Finding Franklin's Fate

Rae traveled a long way to deliver his report to London in 1852. He proposed to return to the Arctic. He picked up two boats and left in June 1853. He found a new river but had to turn back and winter at his old camp.

On March 31, 1854, he left again. Near Pelly Bay, he met some Inuit. One had a gold cap-band. The Inuit said it came from a place where about 35 kabloonat (Europeans) had starved to death. Rae bought the cap-band and offered to buy anything similar.

On April 27, he reached frozen salt-water south of what is now Rae Strait. He then turned north along the western part of the Boothia Peninsula. This was the last uncharted coast of North America. He hoped to reach Bellot Strait and complete the map of the Northwest Passage.

On May 6, he reached his furthest north point. He realized that King William Island was indeed an island. Some historians believe Rae effectively discovered the final link in the Northwest Passage, which was later sailed by Roald Amundsen.

With only two men fit for travel, Rae turned back. On May 26, he found more Inuit families who had come to trade items. They said that four winters ago, other Inuit had met about 40 kabloonat dragging a boat south. Their leader was a tall man with a telescope, likely Francis Crozier, Franklin's second-in-command. The Inuit understood that the ships had been crushed by ice and the men were going south to hunt. When the Inuit returned the next spring, they found about 30 bodies and signs of cannibalism.

One of the items Rae bought was a small silver plate. It had "Sir John Franklin, K.C.H" engraved on the back. With this important information, Rae decided not to explore further. He left Repulse Bay in August 1854.

Later Years and Legacy

With the money he received for finding evidence about Franklin's expedition, Rae ordered a ship called the Iceberg. It was built in Kingston, Canada. Rae moved to Hamilton in 1857.

Sadly, the Iceberg was lost with all seven men on board during its first commercial trip in 1857. Its wreck has never been found. In Hamilton, Rae helped start a scientific organization that is now one of Canada's oldest.

In 1860, Rae worked on a telegraph line project, visiting Iceland and Greenland. In 1864, he surveyed another telegraph line in western Canada. In 1884, at age 71, he was still working for the Hudson's Bay Company, exploring for a proposed telegraph line from the United States to Russia.

Death and Recognition

John Rae died in Kensington, London, on July 22, 1893. A week later, his body was buried at St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall in Orkney.

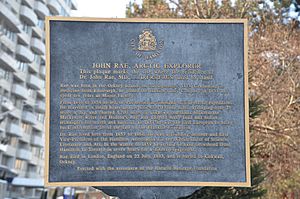

Many places are named after him, including Rae Strait, Rae Isthmus, Rae River, Mount Rae, Point Rae, and Rae-Edzo.

Because of Lady Franklin's efforts to honor her husband, Rae, who had found less glorious evidence, was somewhat ignored by the British establishment. Even though he found the first clues to Franklin's fate, Rae was never made a knight. He died quietly in London. In contrast, another Scottish explorer, David Livingstone, was buried with great honors.

However, historians now recognize Rae's important role in finding the Northwest Passage and learning what happened to Franklin's crew. Authors like Ken McGoogan note that Rae was unique because he was willing to learn from and adopt the ways of Indigenous Arctic peoples. This made him a top expert in cold-climate survival and travel. Rae respected Inuit customs and skills, which was unusual for many Europeans in the 1800s.

In 2004, a Member of Parliament for Orkney and Shetland, Alistair Carmichael, suggested that Rae should have received more public recognition. In 2009, he asked Parliament to state that memorials to Franklin were wrong for saying he discovered the Northwest Passage. In October 2014, a plaque honoring Rae was placed in Westminster Abbey.

John Rae is shown in the 2008 movie Passage. In June 2011, a blue plaque was put on the house in London where John Rae spent his last years. In 2013, a statue of Rae was put up in Stromness, Orkney, to celebrate his 200th birthday. The John Rae Society was also formed in Orkney to promote his achievements.

See also

In Spanish: John Rae para niños

In Spanish: John Rae para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |